Issue Brief: The Big Government Socialism Bill Jeopardizes the Future of Prescription Drugs for Americans

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Big Government Socialism Bill uses sweeping price controls and broad government intervention to set prices for many medicines in Medicare and in the private health insurance market.

- Government price setting will compromise access to lower-cost generic medicines.

- The Big Government Socialism Bill will likely lead to higher list prices, particularly when new medicines are launched.

- Government price setting negatively impacts innovation and will result in fewer new medications.

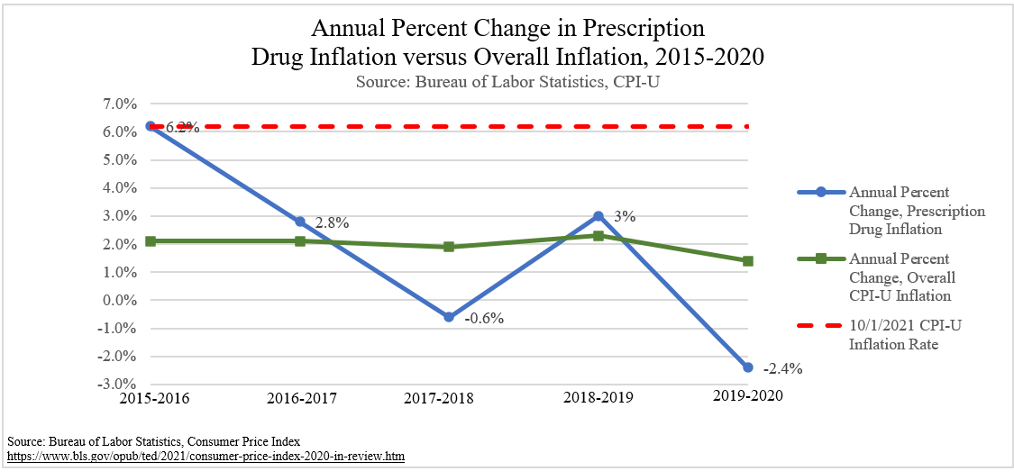

- The Big Government Socialism Bill will allow seniors’ drug prices to increase to October 1, 2021 inflation levels of 6.2%.

- These far-reaching reforms are the wrong way to combat high drug prices and will likely have adverse effects on patients.

President Biden and House Democrats are touting H.R. 5376, the “Build Back Better Act,” which passed the House of Representatives on November 19, 2021, as a supposed solution to high drug costs in Medicare.[1] The bill, commonly referred to as the “Big Government Socialism Bill” uses expansive price controls, such as price negotiation and inflation caps, that will likely lead to less innovation, fewer generic drug approvals, and higher launch prices for new medicines.

Under current law, drug prices in Medicare Part D are determined through negotiations between pharmacies, manufacturers, and prescription drug plans. The government is prohibited from interfering in these negotiations by the non-interference clause, an important provision of Medicare Part D since its passage in 2003.[2] Among other changes, the Big Government Socialism Bill creates exceptions in the non-interference clause. The exceptions would permit the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to effectively set prices for some medicines through “negotiation.” This issue brief will focus on two key drug pricing mechanisms in the bill:

1) Empowerment of the Secretary of HHS to dictate prices for up to 20 medications annually in Medicare Part D initially and later in Medicare Part B.[3]

2) Creation of penalties for companies who raise prices beyond inflation in Medicare Parts B and D and the private health insurance market.

These provisions are the wrong way to combat high drug prices. Reforms to lower drug costs in Medicare should be targeted to minimize unintended consequences. Research shows that government “negotiation” results in less innovation and restricts access to new medication for patients over time. Furthermore, the inflation penalties may result in higher list prices in both the Medicare and non-Medicare markets.

BACKGROUND ON PRIOR FEDERAL POLICY EFFORTS

Over the past several years, lawmakers have proposed an array of price control policies in efforts to lower prescription drug costs, which is a top priority of Americans.[4] Proposals supported by Republicans tend to have a targeted, narrow scope to address persistent market failures while proposals supported by Democrats tend to have broader government involvement and interfere with plans in the private market, a trend that continues with the Big Government Socialism Bill.[5]

International Price References: It is well-known that Americans unfairly subsidize biopharmaceutical innovation for the world, with the U.S. paying significantly more for the same medications than do other developed nations that have government-run health systems.[6],[7] The Trump Administration attempted to address this by using an international price index to narrowly target the prices of 50 high-cost medications in Medicare Part B, which accounted for nearly 80 percent of Part B spending.[8],[9],[10] In contrast, Speaker Pelosi’s H.R. 3 “Lower Drug Costs Now Act”[11] gave the Secretary of HHS the authority to negotiate prices for 250 high-cost drugs in Medicare Parts B and D using an international reference price as the index metric for the price ceiling, created an excise tax on gross revenues for non-participation, and extended the negotiated prices to the drugs sold in the private health insurance market.[12] In addition to its broad scope, H.R. 3’s price negotiation mechanism is concerning because the weakened non-interference clause referenced above could be viewed as a gateway to extending future negotiation power to the private sector.

Inflation Rebates: This policy would require drug companies to make payments to the federal government if they raise drug prices higher than a specified inflation rate. Inflation rebates were proposed in H.R. 3 and the bipartisan S. 2543, both from the 116th Congress.[13],[14] The provisions differed on the year used for the inflation-adjusted price and number of drugs included, with S. 2543 applying to brand and biologic drugs only and H.R. 3 applying to brands, biologics, and biosimilars in Part B and all drugs in Part D.[15] Notably, both bills applied to Medicare Parts B and D, but H.R. 3 included language for extension to group health plans after specific evaluation and reports by the Secretaries of Labor, Treasury, and HHS.[16] Additionally, one of the Trump Administration’s proposed reforms to lower prescription drug prices involved an inflation limit for the reimbursement of Part B drugs. This policy was proposed in the FY2019 budget proposal and functioned to limit the amount Medicare would reimburse Part B drugs to inflation.[17]

PRICE NEGOTIATION

“Negotiation” is Nothing More than Price Controls

Supporters of the Big Government Socialism Bill claim that the legislation allows the Secretary of HHS to “negotiate” drug prices with manufacturers through the creation of a “Fair Price Negotiation Program.” Any examination of the bill text proves that this term is misleading—this is nothing more than price control measures that will harm innovation and lead to fewer new medicines for seniors, undermining the long-term health outcomes of Americans.

The bill describes a process where the Secretary of HHS gathers information from drug companies, publishes a list in the Federal Register of the 100 total drugs covered by both Medicare Parts B and D with the highest total expenditures, and then selects up to 20 drugs per year to add to the cumulative list of negotiated drugs, for which the Secretary then submits “offers” stating the “maximum fair price” that Medicare will pay for the drugs.[18] The bill contains strict ceilings that “negotiated” prices can’t exceed. To make companies comply with these price controls, those who don’t agree to the Secretary’s offer price will be subject to a 95 percent excise tax.[19] Notably, the tax cannot be deducted, meaning that the penalty could cost more than the value of sales. This immense tax makes the “offer” seem like more of a demand.

Price ceilings, in other words, are the maximum amount the Secretary is legally authorized to offer to companies, and range from 40 to 75 percent of the non-federal average manufacturer price (AMP).[20],[21] The specific ceiling within that range depends on how long it has been since the initial exclusivity period expired.[22]

With artificially low “maximum fair prices” dictated by government, companies would invariably push for the price to be set at the maximum amount of the average manufacturer price for a drug in the “Fair Price Negotiation Program,” and companies are unlikely to accept any amount much less than that maximum. While the legislation contains strict price ceilings, it fails to contain any permanent price floors—greatly tilting the playing field by giving outsized leverage to the government—which is a glaring omission that even the more extreme Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3) contained.[23]

It is worth mentioning that prices for drugs in Medicare are already negotiated, just not by the Secretary of HHS. Prices for drugs offered to seniors are reached by negotiations between pharmacies, manufacturers, and prescription drug plans. Government price negotiation would usurp the leverage that drug plans and pharmacies currently have to negotiate drug prices for Medicare beneficiaries and could undermine the discounts seniors currently receive in their drug coverage.

Price Controls Prevent Creation of More Affordable Generics

Another impact of the Big Government Socialism Bill will be reduced incentives for creating generic medications. The highest price for “negotiated” medicines decreases as the drug exits its initial exclusivity period. This creates a shrinking window of time for generic manufacturers to develop and gain FDA approval for a lower cost, generic alternative to pricey medications. Simply put, the market share a generic medication could have narrows over time, and price controls jeopardize the generic manufacturer’s ability to recover profits to make the process of bringing the drug to market worthwhile.[24],[25]

By making it more difficult to bring generics to market, these policies will likely lead to fewer generics available to Medicare patients, which could push seniors onto more expensive branded drugs, leading to increased individual out-of-pocket costs on prescription drugs and a higher total cost of the program. It could also lead to longer monopolies for expensive branded drugs and reduce patient access to affordable generics and biosimilars.[26]

Considering that generics typically cost between 80 to 85 percent less than branded drugs, policymakers should consider legislation that encourages the development of generics.[27] Generic medicines account for 90 percent of all prescriptions but make up only 18 percent of total drug spending. Over the past decade, generics have saved Americans more than $2 trillion.[28] More medicines on the market, especially generics, mean more competition, which in turn lowers prices for individuals and for private payers.[29],[30] Legislative efforts to encourage growth in the generic medicine market are typically bipartisan, and a recent Biden Administration plan to address drug prices includes this recommendation.[31],[32] These efforts contrast with the impact that price controls from the Big Government Socialism Bill will have on the generic market and could hurt seniors on fixed incomes who are already struggling with inflationary pressures.

Build Back Better Will Hinder Pharmaceutical Innovation

As outlined above, the price control measures in the Big Government Socialism Bill are little more than a retread of bad policies. They are similar to the Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3), which passed in the House of Representatives in the previous Congress.[33] Several studies have measured the possible effects of the price control policies in H.R. 3, and a new independent analysis has measured the effects of the Big Government Socialism Bill. Although the studies’ findings differ on the severity of the impact that price controls have on the pharmaceutical marketplace, all conclude that there will be a revenue reduction resulting in fewer new drug approvals, meaning there will be fewer new medicines available. Patients and policymakers should be concerned about reduced health outcomes because of fewer new medications, particularly as they impact life expectancy and lost life years.

A new analysis from the University of Chicago measured the effects of the price control policies in the Big Government Socialism Bill.[34] Overall, the study estimated a 12 percent reduction in global revenues for pharmaceutical companies through 2039, with an 18.5 percent reduction in R&D, leading to 135 fewer new drugs during that time period. The negotiation provisions account for $987 billion of the reduced revenue, which is 34 percent of the total decrease. This could lead to 331.5 million life years lost through 2039, which the authors compare to the 10.7 million life years lost to COVID-19.[35] Similar to the authors’ previous analysis of H.R. 3,[36] they estimated a much larger effect of H.R. 5376 on the reduction of new drugs than did the CBO, which found only five fewer drugs would be approved through 2039.[37] The authors further offered insight into how different methodologies, including approaches to innovation, could have contributed to the differences.

The official Congressional Budget Office (CBO) score for H.R. 3 concluded that a 15 to 25 percent revenue reduction would occur, resulting in a 0.5 percent average annual decrease in the number of new drug approvals in the first decade, increasing to an eight percent annual average decrease in the third decade after implementation.[38]A full discussion of the differences between the previously referenced study and the CBO score can be found in the University of Chicago analysis with the authors making the case that their estimates are still conservatively low despite being much larger than those from CBO.[39]

The Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) estimated that H.R. 3 could result in up to 100 fewer new drugs over the next decade, or about one-third of the total number of drugs expected to enter the market during that time. The CEA also found that by limiting access to lifesaving drugs, price controls in H.R. 3 would reduce Americans’ average life expectancy by about four months—nearly one-quarter of the projected gains in life expectancy over the next decade.[40] Reductions in R&D because of price controls therefore jeopardizes access to new drugs and harms health outcomes for seniors. Another study concluded that the medical expenditure needed to gain one life-year is about $11,000, whereas the pharmaceutical R&D expenditure needed to gain one life-year is about $1,345.[41]

Reforms to Medicare should encourage innovation in the pharmaceutical sector because treatment through medication equates to less spending on expensive surgeries or emergency room visits. For example, a Medicare beneficiary who takes a prescription to manage cholesterol may prevent a costly and possibly life-threatening trip to the emergency room for a heart attack.[42] A government study estimated that a one percent annual increase in the number of prescriptions translates into a 0.2 percent decrease in annual healthcare costs, working out to about $94 saved per prescription.[43] Another study found that obtaining Medicare Part D insurance is linked to an eight percent decrease in the number of hospital admissions, a seven percent drop in Medicare expenditures, and a 12 percent decrease in total resource use.[44]

Smart spending on pharmaceutical drugs prevents expensive hospital visits and actually saves our health system money. Lawmakers should reject harmful sweeping price control measures that would prevent lower-cost generics from entering the market, hinder pharmaceutical innovation, and lead to fewer new drugs. Fewer new products on the market also could lead to less price competition and higher costs for existing medicine.

INFLATION CAPS

Inflation Caps Equal Higher List Prices

Inflation is a top concern of Americans right now as prices at the grocery store and gas pumps continue to rise, with 92 percent of voters saying inflation “is a serious problem.”[45] The Big Government Socialism Bill may cause Americans to also experience inflation with prescription drugs due to the impact of inflation caps in Medicare Parts B and D and in private health insurance plans.[46]

Referred to as “Prescription Drug Inflation Rebates,” the Big Government Socialism Bill would require branded, or single-source, drug manufacturers who sell drugs in Medicare Part B and most covered drugs in Medicare Part D to pay penalties if they raise prices above the rate of overall inflation in the economy. In Part B, the manufacturer would pay the federal government a penalty of either 106 percent of average sale price (ASP) or the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) for the calendar quarter, times the total number of billing units sold.[47] If a company refuses to comply, they must pay 125 percent of that amount. In Part D, the rebate will be set as the total number of units of the drug sold multiplied by the amount by which the annual manufacturer price (AMP) exceeds the CPI inflation adjusted price amount.[48] By including the total units sold outside of Medicare, both provisions extend the Medicare Part B and D inflation caps to the private health insurance market, magnifying the scope of damaging effects.

According to the bill, the initial inflation rate that companies would be limited to is tied to the inflation rate as of October 1, 2021—which was 6.2 percent[49]—after which the inflation rate is adjusted quarterly according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). To compare, the inflation caps in H.R. 3 began at January 2016 levels, which were 1.4 percent, and the ideal benchmark rate has been a point of debate for Democrats during bill negotiations.[50],[51] This means that the new legislation permits prescription drug companies to raise their prices up to 6.2 percent at first, without penalty. As a point of reference, analysis of Medicare Part D prescription drug inflation rates from 2018-2019 found that only half of drugs had list price increases above the then inflation rate of 1.8 percent.[52] Importantly, 38 percent of drugs had list price decreases and 40 percent of the highest utilized drugs had list price increases below five percent during the analysis period.

Making prices “sticky” in this manner may cause companies to preemptively raise prices up to the inflation ceiling—even if they would have raised them by a smaller amount absent the caps—as a way to frontload future price increases that they would no longer be able to do in response to the real-time evolution of market conditions.[53] Thus, the inflation cap could act as both a ceiling and a floor for price increases.[54] Inflation rebates also incentivize pharmaceutical manufacturers to employ higher list prices when launching new medications, and may even end up costing Medicare and commercial insurers more money than it would have saved.[55] Higher launch prices could be particularly problematic for Medicare Part B due to its established 106 percent ASP reimbursement formula.

Inflation Caps Have Unknown Unintended Consequences

Inflation rebates in Part D, though intentioned to lower costs for patients, could result in higher premiums for Medicare beneficiaries. Part D plans use rebates from drugmakers to lower premiums. Because drugmakers will be prohibited from raising drug prices above the inflation threshold, inflation caps will limit prices and may result in fewer rebates as the gross price approaches the net price. As a result, Part D premiums are expected to increase. The CBO score for H.R. 3 concluded that inflation caps in that bill:

“would lead to decreases in manufacturer rebates and increases in prices at the point of sale…The reductions in Part D costs would result in lower Federal Government spending ($195 billion) and increased State spending ($2 billion). Beneficiary spending would increase by $30 billion, with premiums increasing by $24 billion primarily as a result of the substantial rebate reduction and cost-sharing responsibility increasing by $6 billion due to higher list prices.”[56]

Inflation caps could therefore directly increase seniors’ out-of-pocket spending and premiums for Part D coverage, which is counter to the goal of inflation caps: reducing drug costs.

Inflation rebates in Medicare could significantly reduce innovation by producing the same harmful effect as price negotiation—decreased revenue to drugmakers. The previously discussed University of Chicago economic analysis of the Big Government Socialism Bill concluded that the inflation rebate provisions contribute to 61 percent ($1.8 trillion) of the overall 12 percent ($2.9 trillion) decrease in global revenue that would result in 135 fewer drugs by 2039.[57] Notably, this analysis only included drugs in Medicare, which makes up just 28.3 percent of the overall prescription drug market. The negative effects of decreased revenue and less new drug development could be greater if the bill text that includes the commercial health insurance market in inflation rebates becomes law.[58]

The Big Government Socialism Bill that passed the House extends inflation rebates to the commercial health insurance market. However, there is ongoing debate among policy experts on the need for this extension due to conflicting evidence on potential cost-shifting effects of inflation cap policies if they do not extend to the commercial health insurance market. For comparison, H.R.3 and S. 2543 included inflation rebates in Medicare Parts B and D only. One policy expert makes the case that prescription drug inflation caps in Medicare would not lead to cost-shifting in the form of higher prices in non-Medicare markets.[59] Similarly, a 2019 Congressional Budget Office preliminary report on inflation rebate provisions in Medicare Part D estimated that commercial health insurance plans could have potentially lower costs for prescription drug benefits.[60] Conversely, another source predicts increased drug costs in the commercial health insurance market as a result of cost-shifting due to inflation caps.[61] The same source later predicted the opposite effect of a decrease in drug costs in the commercial health insurance market if inflation caps are extended to private insurers, as they are in H.R. 5376.[62] CBO has not provided a specific analysis on the Big Government Socialism Bill’s effects on the private health insurance market as of this papers’ publishing. The provisions, as currently written, have a reportedly uncertain future as the reconciliation process moves to the Senate, where the Senate Parliamentarian will determine if they impact federal spending or revenue.[63],[64]

Overall, implementing this broad policy at this time is counterproductive because prescription drug inflation has decreased for the past two years while the overall CPI has increased. As of September 2021, prescription drug prices decreased by 1.6% from the previous year.[65] The figure below shows that from 2015-2020, the annual percent year-to-year change of prescription drugs according to the CPI decreased from a high of 6.2 percent from 2015-2016 to -2.4 percent from 2019-2020. Under the Big Government Socialism Bill, drug prices could rise to the current inflation level of 6.2%, and then continue to rise with inflation each year. This policy may have the opposite intended effect by encouraging higher initial list prices and annual price increases across most covered drugs in Medicare and non-Medicare markets.

CONCLUSION

The Big Government Socialism Bill contains expansive policies that will have grave implications for Americans. Price controls will reduce the amount of new drugs and lower-cost generics. Inflation caps may lead to higher launch prices and a higher likelihood of annual price increases. High prescription drug prices and persistent market failures in the U.S. need to be addressed through the narrowest possible policy interventions that benefit Americans through increased competition and continued innovation. Seniors and all Americans deserve better than the sweeping proposals Congress is considering.

[3] Drugs covered under Medicare Part B are exempt from price negotiation until 2027.

[5] https://files.kff.org/attachment/Slideshow-Latest-Prescription-Drug-Proposals-Trump-Biden-Congress.pdf

[6] https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Funding-the-Global-Benefits-to-Biopharmaceutical-Innovation.pdf

[8] https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-most-favored-nation-model-medicare-part-b-drugs-and-biologicals-interim-final-rule

[10] https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//197401/Part-B%20Drugs-International-Issue-Brief.pdf

[15] https://files.kff.org/attachment/Slideshow-Latest-Prescription-Drug-Proposals-Trump-Biden-Congress.pdf

[17] See page 20, American Patients First Plan: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/AmericanPatientsFirst.pdf

[18] The number of new drugs the Secretary is permitted to negotiate prices for is limited to 10 in 2025, rises to 15 in 2026 and 2027, and 20 in 2028 and subsequent years. The list is cumulative, meaning that by 2028, there could be as many as 60 drugs in the fair price negotiation program.

[19] The excise tax begins at 65% for the first 90 days of noncompliance, increases to 75% from days 91 to 180, is 85% for days 181 to 270, and increases to 95% in subsequent days of noncompliance. See page 2029 of HR 5376: https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf

[20] See page 2006, HR 5376, Build Back Better Act: https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf#page=878.

[21] The Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) is the average price paid to the manufacturer by wholesalers and retail pharmacies that purchase drugs directly from the drug manufacturer. This price includes any discounts or rebates. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-05-00240.pdf

[22] The initial exclusivity period ends after 9 years for small molecules and 13 years for biologics. “Short-monopoly drugs”, are identified in H.R. 5376 as drugs “(other than a post-exclusivity and a long-monopoly drug)”, or drugs that are less than 12 years from their initial FDA approval, and have a maximum allowed price of 75% AMP (See page 2006). “Post-exclusivity drugs,” are defined as drugs between 12 and 16 years past their initial FDA approval, and have a maximum allowed price of 65% AMP (page 2006). “Long-monopoly drugs,” defined as drugs that are at least 16 years past their initial FDA approval (page 2007) and have a maximum allowed price of 40% AMP (page 2006). https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf#page=878

[23] In 2028 and 2029, there would be a temporary floor of 66 percent of the non-federal AMP for select small biotech companies. See page 2008 of H.R. 5376: https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf#page=878.

[24] https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/medicare-negotiations-serve-catalyst-perpetual-monopoly

[25] https://ecchc.economics.uchicago.edu/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Drug-Pricing-in-HR-5376-11.30.pdf

[30] https://www.aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//198346/medicare-part-d-generic-comp.pdf?_ga=2.144393013.148913165.1638921426-1209826393.1614979161

[31] In reference to bipartisan legislation to encourage the growth of generics: https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-leahy-hail-inclusion-creates-act-year-end-spending-agreement

[32] See page 9: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/Competition%20EO%2045-Day%20Drug%20Pricing%20Report%209-8-2021.pdf

[33] The Lower Drug Costs Now Act passed in the House of Representatives in 2020. The price control mechanisms in H.R. 5376 are similar to H.R. 3 in that they both require certain drug manufacturers of covered Medicare Part D drugs to negotiate prices with the Secretary of HHS, prices are capped at 120% of AIM, an excise tax of 95% is established as penalty for companies that refuse negotiation, and price increases would be capped at inflation. Two key differences between the two bills is that H.R. 3 extended the negotiated price to private insurers and used international reference pricing. For more details, see H.R. 3, the Lower Drug Costs Now Act: https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr3/BILLS-116hr3pcs.pdf

[34] https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/d/3128/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Drug-Pricing-in-HR-5376-11.30.pdf

[35] 10.7 million life years lost due to COVID-19 is calculated as of the study publishing date of November 2021.

[36] See the Philipson and Durie analysis of H.R. 3, https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/d/3128/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Price-Controls-and-Drug-Innovation-Philipson.pdf

[39] https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/d/3128/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Price-Controls-and-Drug-Innovation-Philipson.pdf

[40] https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/articles/house-drug-pricing-bill-keep-100-lifesaving-drugs-american-patients/

[45] https://scottrasmussen.com/92-say-inflation-is-a-serious-problem-56-say-build-back-better-plan-will-make-it-worse/

[47] This penalty calculation excludes the number of billing units sold under Medicaid.

[48] This penalty calculation excludes the number of billing units sold under Medicaid.

[50] See HR 3, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3/text. The January 2016 inflation rate was 1.4%, https://cpiinflationcalculator.com/2016-cpi-and-inflation-rate-for-the-united-states/

[51] https://www.huffpost.com/entry/democrats-prescription-drug-prices-government-negotiations-inflation_n_61809b09e4b059d0bfc1ed08

[52] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/price-increases-continue-to-outpace-inflation-for-many-medicare-part-d-drugs/

[55] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-build-back-better-act/#_Require_Inflation_Rebates

[56] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/Downloads/HR3-Titles-I-II.pdf

[57] https://ecchc.economics.uchicago.edu/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Drug-Pricing-in-HR-5376-11.30.pdf

[58] https://ecchc.economics.uchicago.edu/files/2021/08/Issue-Brief-Drug-Pricing-in-HR-5376-11.30.pdf. The authors state: “…we assume Medicare prices will increase at a 2 percent annual pace while all other pharmaceutical spending (the other 71.7 percent) increases at a 4.5 percent rate…”.

[59] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2021/09/24/cost-shifting-in-drug-pricing-or-the-lack-thereof/

[61] https://www.westhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/HR3ANALYSISCOMMERICALMARKET.pdf. On page 3 in Exhibit 1A, Scenario B, Title II, the authors estimate a 2.2% increase in commercial market claims cost by year (total medical and drug) from 2023-2029.

[62] https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5e59d7f99e288f91abe20b9f/618196e2fc84e784374c03e3_WST04.HR3%20Analysis.20211102%20(002).pdf. On page 3 in Exhibit 1A, Scenario B, Title II, the authors estimate a 6.8% decrease in commercial market claims cost by year (total medical and drug) from 2023-2029.