Improving the Foster Care and Adoption Systems in the United States

Key Takeaways

391,000 children in the U.S. are currently in foster care, indicating a system significantly affecting many vulnerable individuals.

33% of foster children experience instability with at least three placements per year, highlighting a critical need for improved placement processes and support for stable environments.

Of the 53,500 children and youth who were adopted in 2021: 55% were adopted by their foster parent(s) and 34% by a relative.

20% of youth aging out of the system experience immediate homelessness, demonstrating a significant failure to provide adequate support for their transition into adulthood.

Reforms should include increased support for faith-based organizations and partners, expanded tax credits for foster families, better support for parents, and stronger data on children in care to improve placement processes.

In addition to reform, prevention efforts and family connections should be improved and expanded upon via programs such as CarePortal to decrease the number of children entering foster care and promote family unity.

Introduction

The U.S. has long valued caring for society’s most marginalized members, yet our foster care and adoption systems are not adequately ensuring that every child has access to a stable, loving home. This is due not only to financial roadblocks but also outdated legislation, overburdened caseworkers, and insufficient preventative measures in many states.

Despite the innate need for stability felt by our most vulnerable youth, reforming the foster care system has not been a priority in the Biden Administration. In fact, the current leadership has been detracting from meaningful progress made during the Trump Administration. The foster care system and its partner organizations, particularly those with religious roots, continue to face challenges that make it impossible for them to fulfill their missions.

States and communities are legally obligated to care for the Nation’s most vulnerable children (The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, n.d.). With 3.2 million paternal, maternal, or double orphans in this country (The Census Bureau, 2023), we must implement solutions. Immediate reform is needed to support foster parents better, strengthen faith-based adoption programs, and ensure children are placed in the right homes, whether temporarily with foster parents or permanently with adoptive parents.

Foster Care Statistics

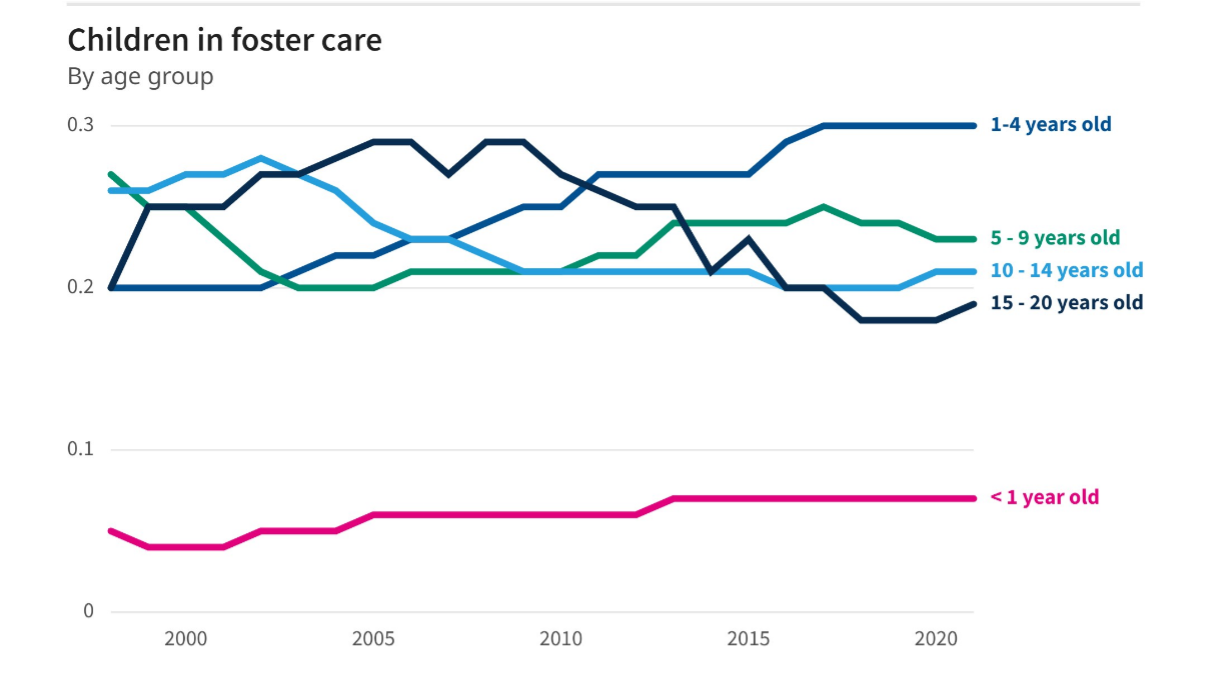

Children who spend time in foster care are particularly vulnerable due to their heightened developmental and mental health needs, as well as the complex trauma that comes with being separated from their biological parents (Turney, 2016). According to the most recent statistics available, 391,098 children were living in foster care in 2021 (Foster Care and Adoption in the U.S., 2023). About one-third of these children were between the ages of 1 and 5 years, and seven percent were babies. On average, one-third of foster children experience a change in their living arrangements at least three times per year. The number of children waiting to be adopted, a subset of those in the foster care system, includes children whose parents have had their parental rights terminated. Today, about 117,000 children are waiting to be adopted (Statista, 2023).

State foster care systems face many complexities, including how best to support youth who age out of the system. While today most children in foster care are under the age of 10, in the early 2000s, youth ages 15–20 were the most represented group. Between 2003 and 2010, this age group averaged 28 percent of all young people in care, and by 2021, they had trended downward to 19 percent. Young adults ages 18–20 may remain in foster care provided they are in school, enrolled in an employment program, working, or incapable of school or work due to a medical condition.

More than 23,000 children age out of foster care each year, usually when they turn 18 (National Foster Youth Institute, 2023). At that point, 20 percent instantly become homeless, 70 percent become pregnant before turning 21, and 25 percent suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Fowler et al., 2017; Combs et al., 2017; Plotkin, 2005). Not only are these young adults more likely to experience homelessness, early parenthood, and mental health issues, but they are also prone to physical health problems, employment and academic difficulties, incarceration, and other potentially lifelong adversities.

Foster children have rates of depression and anxiety that are seven times higher than those of children who did not spend time in foster care (Turney & Wildeman, 2016). They also have lower test scores and graduation rates (Barrat & Berliner, 2013). These disadvantages continue into adulthood, with nearly 20 percent of the U.S. prison population being made up of people who were in foster care as children (U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2021). Those who turn 18 in foster care report 50 percent lower earnings and employment rates than a sample of young adults with similar levels of education who did not spend time in foster care (Okpych & Courtney, 2014).

Understanding the outcomes for young adults who have been in foster care is critical to shaping the services and support they need. Their vulnerabilities can be addressed and positively influenced by policies and practices that ensure culturally responsive and trauma-informed transition services and support. This can help them navigate the steps to adulthood, garner stability, and reach their full potential.

Reforms are needed to support children who age out of the foster care system better. While some states technically allow youth to extend foster care placement temporarily after they turn 18, these young people must meet certain eligibility requirements. Only 28 states offer extended benefits for 21-year-olds (Rosenberg & Abbott, 2019). Extending support services, such as those in the Family First Act (discussed in detail later), would help pave the way for a successful entry into the community.

For example, policies that extended support services beyond the age of 18 or 21, depending on the jurisdiction, would help these young adults transition into independent living. States should ensure that caseworkers are available to help with forming self-sufficiency plans. In 23 states and the District of Columbia, state law prioritizes self-sufficiency measures to ensure that youth receiving services are either working to complete a high school diploma, enrolled in a post-secondary or vocational program, or working 80 hours per month—the exception being the inability due to a documented medical condition (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2022). These rules ensure that foster children are on track to provide for themselves and have a promising future.

It is important to address the foster care system’s struggle to find safe and affordable housing for adults aging out of the system. While high rates of mobility and housing instability make this a complex issue, reforms should be put into place to address the needs of those transitioning. A study found that in addition to current and new, reunification can also play a key role (Fowler et al., 2017). The study suggests that focusing on reunification with biological families of origin and providing developmentally appropriate interventions may be more effective in mitigating homelessness risk among youth transitioning to adulthood. This aligns with current trends in some states, highlighting the potential of family connections as a key factor in promoting stability and well-being for young adults leaving foster care.

Foster Care Process

Every state in the U.S. runs a child welfare system through which it investigates reports of child maltreatment, determines whether a child should be removed from the home, and arranges substitute care and other services, such as physical and mental health assistance, to mitigate the effects of maltreatment (How the Child Welfare System Works, 2020). The Code of Federal Regulations defines “foster care” as follows:

Foster care means 24-hour substitute care for children placed away from their parents or guardians and for whom the State agency has placement and care responsibility. This definition includes but is not limited to, placements in foster family homes, foster homes of relatives, group homes, emergency shelters, residential facilities, child care institutions, and pre-adoptive homes (45 C.F.R. § 1355.20, 2011, p. 267).

States have the legal authority to remove children from homes when the children are in imminent danger of harm under their parents’ patriae authority. This allows states to act on behalf of children who cannot act on their own behalf (Ventrell, 2010). Once in foster care, children are entitled by federal law to a permanency plan, with the goal of placing the child in a permanent family, either through reunification with their birth parents, adoption, guardianship, or permanent custody by a relative (Adoption & Safe Families Act [ASFA], 1997).

Adoption or guardianship is considered an appropriate alternative when reunification is nonviable. Federal law requires that to the extent possible while in foster care, children be placed in the least restrictive setting—a placement for a child that, in comparison to all other available placements, is the most family-like setting—near their parents’ home (42 U.S.C.§675(5), 2010) and their school of origin (42 U.S.C.§67(1)(G)(i), 2010). Today, about five percent of all U.S. children are placed in foster care during childhood, and similar rates are found in other countries (Rouland & Vaithianathan, 2018; Yi et al., 2020).

Foster Care Funding

The foster care system is complex and includes federal, state, and local organizations. Child welfare programs in the U.S. began with the Children’s Bureau in 1912, followed by federal funding in the Social Security Act in 1935.

In 2018, President Donald Trump signed the Bipartisan Budget Act 2018 (H.R. 1892). Included in the package was the Family First Prevention Services Act, which included dramatic changes in child welfare systems across the country. A key change pertains to the spending of Title IV-E funds. IV-E is the federal funding source that pays the costs of caring for children in placement and administrative costs for the state’s foster care program. Under the Family First Act, states, territories, and tribes with approved Title IV-E plans can use these funds for prevention services that would allow “candidates for foster care” to stay with their parents or relatives. States are reimbursed for prevention services for up to 12 months. To be eligible for this federal funding, states must opt-in, be compliant with Family First, implement evidence-based services, and have at least 50 percent of expenses for services meeting the highest evidence rating of well-supported. As of October 2023, 43 states have opted in and submitted FFPSA plans, with 28 already approved. Interestingly, these approved plans showcase intriguing measures in various states, potentially paving the way for innovative approaches to child welfare. Family services may be offered in non-crisis situations to families in need. This could include concrete goods, case management, and referrals.

- Mental health intervention and outpatient treatment for foster children.

- Increased support for parents and caregivers.

The federal foster care program pays a portion of states’ costs to provide care for children removed from welfare-eligible homes because of maltreatment. Authorized under title IV-E of the Social Security Act, the program's funding (about $5 billion per year) is structured as an uncapped entitlement so that any qualifying state expenditure will be partially reimbursed or matched without limit. Before Family First, Title IV-E funds could be used only to help with the costs of foster care maintenance for eligible children, administrative expenses, staff training, payments to foster parents and certain private agency staff, adoption assistance, and kinship guardianship assistance.

Foster care stipend rates vary from state to state. Based on recent data, in Alabama, the stipend amount ranges from $462–$501, while in Idaho, it ranges from $329-487. Other examples include Nebraska, with a stipend from $597–$1,047, and Illinois, where it is comparably lower at $26 to $511. Some states, such as Kansas and Arkansas, have introduced legislation to increase the adoption tax credit to account for large percentages of the federal adoption tax credit. Kansas, for example, introduced S.B. 147, which would provide a state tax credit equivalent to 100 percent of the federal adoption tax credit. In Kansas, the bill would increase, beginning in tax year 2023, the adoption tax credit to 100 percent of the federal adoption tax credit for most children and to 150 percent of the federal adoption tax credit if the child was a Kansas resident before the adoption and is a child with special needs, as defined in federal law. This means that costs relating to caring for the child will be refunded, making adoption more feasible for parents.

The Children's Bureau is responsible for enacting federal child and family legislation within the Administration for Children and Families and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Child welfare agencies spend more than $30 billion each year on child protection, with about half of their funding provided by the federal government (Child Welfare: Purposes, Federal Programs, and Funding (fas.org)). Every state provides a subsidy to parents to cover the basic costs of raising a child.

Despite the policies in place to help them, foster parents are often under significant financial stress. They receive a stipend only to help cover the costs of caring for a foster child, and it is often insufficient, especially for children with special needs. Financial difficulties can put additional stress on foster families already dealing with the emotional and logistical challenges of foster parenting. States need more federal or state foster care funding to recruit foster parents.

Foster Parents

While being a foster parent is a noble and rewarding endeavor, it is also fraught with challenges due to the complexities of the current system. One of the primary difficulties foster parents face is the lack of adequate support and resources. Foster children often come from traumatic backgrounds and may have special needs or behavioral issues. Foster parents often report feeling ill-equipped to handle these challenges due to insufficient training and lack of access to necessary services, such as therapy or tutoring. While the average cost of raising a child in the U.S. was $290,014 in 2022, the average cost of fostering a special needs child varies depending on the child’s individual needs and the state in which the child lives (LaPonsie, 2020). In some cases, the cost can exceed the average cost. Foster parents, in general, receive a monthly stipend from the state to help cover the costs of caring for a child. Because many children adopted from the public child welfare system have experienced loss and separation from their families and communities, they may have unique mental and emotional needs. Some may require ongoing medical care. States usually cover these costs through the Medicaid system.

In 2017, research published in the Journal of American Medicine Association Pediatrics (2017) found that from 2000 to 2017, children entering foster care due to parents’ drug use increased by 147 percent. The turnover rate of foster parents ranges from 30 percent to 50 percent each year[1] (National Foster Youth Institute). Turnover was calculated as annual exits divided by the number of active licenses at the beginning of the year.

Several issues stand in the way of connecting foster and adopted children with loving homes. These include a child welfare system that foster parents feel is unsupportive and keeps children in temporary placements when they could benefit from permanent adoptive parents. A 2007 Harris Interactive study found that 75 percent of adults who had ever fostered or adopted reported dissatisfaction with the support they received from the child welfare agency either before or after placement (Atwood, 2011).

One cause of this dissatisfaction is funding—states spend little of their federal or state foster care funding on recruiting and retaining foster care parents. This has led to many qualified, licensed foster parent homes not being matched with foster children. To address this and better meet the needs of foster parents, agencies should put funding toward targeted recruitment strategies that match individuals based on specific needs. Agencies also should treat all parents, including foster parents, as partners. This could include assigning agency staff to work with specific foster families as they navigate the application process, helping families with required documents, and helping potential foster families identify community resources available to them. Simple steps, such as setting 24-hour response deadlines for potential foster or adoptive parent questions and concerns, would also help (Casey Family Programs, 2014).

Although many Americans may be interested in becoming foster parents (Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption, 2017), a study by HHS shows that about half to two-thirds of foster parents discontinued their service within one year of having the first foster child placed in their home (Gibbs, 2004). According to a study by HHS, roughly one-half to two-thirds of foster parents discontinued their service within one year of having their first foster child placed in their home (Gibbs, 2004). Researchers also found that 25 percent of new foster homes stop providing care in less than four months (Wulczyn et al., 2018).

Comprehensive reform is crucial to support these dedicated individuals better and ensure the well-being of foster children. This could include better training and support for foster parents (often offered by faith-based programs), increased training to provide stability for foster placements, streamlined bureaucracy, and adequate financial compensation.

Faith-Based Resources and Adoption

Faith-based organizations have played an important role in the child welfare system throughout America’s history and are often considered the most accommodating toward special-needs children (Howell-Moroney, 2009; Orr et al., 2004). Many faith-based programs are specifically aimed at the challenges of recruiting and retaining foster and adoptive parents. The passage of the Charity, Aid, and Recovery Act of 2002 is often seen as a critical moment when faith-based organizations (FBOs) began playing a more prominent role in providing public services in the U.S. By some estimates, congregations, religious charities, and other FBOs are now the third-largest component of the non-profit sector, only after secular health and educational organizations (Vidal et al., 2001).

One example is the One Church One Child initiative, which was established in 1980 by Father George Clements to help the state of Illinois partner with African American churches to recruit African American adoptive parents. As part of the partnership, churches accept the responsibility to recruit at least one adoptive and foster family from their congregations. This program has been replicated in more than 35 states and has proven to be successful in reducing the number of African-American children waiting for permanent homes across the Nation (Talley, 2008).

For the program to be successful, partnership between the faith community and public agencies is vital. One Church One Child initiatives use a variety of recruitment strategies, invest time in training local church liaisons, and measure participation levels that identify how many churches are supportive and are in partnership. Another key to their success is providing consistent follow-up with adoptive families, especially during the post-placement period. This can include newsletters, e-mail distributions, website postings, phone calls, and even family retreats. This type of communication and consistency sets them apart from other initiatives, as lack of follow-up is a common complaint among foster and adoptive families (Talley, 2008). Faith-based foster care and adoption agencies possess considerable practice wisdom on how to recruit families and sustain relationships.

Lifetime Children Services is a Christian organization that has helped vulnerable children for 40 years. It has served more than 10,000 families, placed more than 4,300 children, and trained almost 1,500 families for fostering (Lifeline Children Services, 2023). It helps foster families, women with unplanned pregnancies, and post-adoptive families with services such as counseling, training, and church initiatives. Lifetime helps families with adoption in all 50 states and internationally.

A faith-driven organization, Lifetime has a mission to equip the Body of Christ to manifest the gospel to vulnerable children. Organizations like this offer a morality-based approach to help address common family issues and mental health struggles. Testimonials demonstrate that such approaches are highly effective in preparing foster families and adoptive families for the tribulations that can arise.

Multiple studies report high numbers of families involved in foster care and adoption through faith-based agencies. A 2009 study provided evidence that onboarding and training experiences for foster parents in faith-based agencies were rated more favorably than the control group (Howell-Moroney, 2009). Faith-based organizations can recruit more caregivers and provide a volunteer network that helps them make it through onboarding challenges to begin and continue fostering.

A 2022 study showed that, compared to a pre-study comparison group, participants in faith-based adoption programs reported higher levels of not feeling like they must cope on their own, willingness to accept a new foster placement, having respite breaks, having someone to call in case of emergency, and being affirmed in their work as a foster family. They also reported feeling more prepared and effective as parents (Hodge et al., 2022). These findings indicate that faith-based programs can provide something to foster parents that other agencies do not—a sense of community, reliance, and confidence.

The left-wing effort to dismantle religious adoption services by imposing requirements that contradict the religious roots of these services is a direct threat to foster children. For example, some state laws require faith-based programs to place children with same-sex couples, which may be in conflict with the programs’ religious doctrine, forcing them to either comply or close their doors. Most notably, The Obama Administration implemented a rule that made federal foster care funding contingent on an agency being willing to place children with same-sex couples (Health and Human Services Grants Regulation, 2016). While the Trump Administration issued a new rule to reverse this, the Biden Administration revoked this waiver in 2021.

This decision risks multiplying the number of foster children who will face mental health issues. A 2015 study conducted by Dr. Paul Sullins found that emotional problems, such as anxiety and identity issues, were more than twice as prevalent for children with same-sex parents as for children with opposite-sex parents. Many states have passed religious exemption laws that allow foster care and adoption agencies the flexibility to not place children in situations that conflict with their deeply held religious beliefs. Other states should follow to protect religious liberty, prioritize children’s mental health, and ensure faith-based organizations are not forced to shut their doors. If states fail to protect religious organizations, other agencies will have to take on larger caseloads, and foster children will be the ones who suffer the consequences.

States have several options to address the religious freedom concerns of some foster care programs. They can require foster care programs to disclose their religious affiliation and policies, in turn helping families make informed decisions about which foster care program is right for them. They can provide financial support to secular foster care programs to help ensure that enough foster care programs are available to serve all families, regardless of their religious beliefs. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the religious freedom concerns that have affected some foster care programs. States will need to tailor solutions to their specific needs and circumstances.

While no comprehensive data is available on the number of religious foster care programs that have been unable to serve families due to religious freedom concerns, several reports have emerged of such cases. In Michigan in 2018, St. Vincent Catholic Charities, a prominent foster care agency, garnered attention for refusing to place a child with a same-sex couple based on religious beliefs about marriage. This refusal led to legal disputes, public discourse, and eventually, the agency withdrawing from foster care services in the state. This case underscores the complex interplay between religious freedom protections and anti-discrimination policies, particularly concerning vulnerable children seeking safe and nurturing homes.

Similar controversies have arisen elsewhere, such as in 2019 when a Christian foster care agency in Texas declined to place a child with a Muslim family. Although the extent of this issue is challenging to quantify without comprehensive data, these individual incidents raise alarms about the potential widespread impact. It is crucial to note that these programs are ceasing operations due to conflicts arising from religious beliefs. The absence of comprehensive data makes it challenging to assess the full scope of religious foster care programs affected by such conflicts. Nevertheless, these specific cases serve as poignant reminders of the possible repercussions, including children left in uncertainty, families deprived of crucial support, and the risk of a fractured foster care system incapable of meeting the diverse needs of all involved.

Foster children need stable, loving homes that provide them with a healthy self-image and family environment. Many state governments hamper civil society’s efforts to serve these children by threatening religious liberty protection for faith-based foster care and adoption providers. This is despite the proven value of traditional family structures and the proven success of faith-based programs. With 391,000 children in foster care and more than 113,000 children waiting to be adopted, all states should be focused on placing children in healthy homes. With the Biden Administration reversing religious exemption waivers in Michigan, Texas, and South Carolina, faith-based partner programs that want to serve their communities through ministry are being debilitated. Placing politics and ideology over the law will harm children and prevent them from being adopted by willing, eligible families.

Foster Care Caseworkers

Foster care caseworkers play a crucial role in the foster care system, as they are the primary link for the child, the biological family, and the foster family. Caseworkers are responsible for ensuring the safety and well-being of the child, coordinating services, and making recommendations on the child’s placement and care. They conduct regular home visits to monitor the child’s progress and assess the suitability of the foster home. Caseworkers also provide support and guidance to foster parents, helping them navigate the system’s complexities and address challenges—these can include the need for training, resources, and respite care. They also work with the biological family, facilitating visits and working toward reunification when it is in the child’s best interest. The foster care system cannot function effectively without caseworkers’ dedication and hard work.

State caseworkers are supposed to work closely with foster parents to help solve problems. However, the caseworker turnover rate is extremely high. According to a study by Flower, McDonald, and Sumski, up to 40 percent of child welfare caseworkers leave their jobs every year nationally, and 90 percent of agencies indicate difficulty hiring and retaining staff (DeGarmo, ED.D., 2017). In a recent review of the literature on the needs of foster parents, several studies noted a need for training focused on foster children’s unique, difficult circumstances, which almost always result in some level of special needs. All foster children are considered special needs in the sense that they have experienced trauma and disruption in their lives. They may have been removed from their homes due to abuse, neglect, or other difficult circumstances. They may have experienced multiple placements, which can be destabilizing and confusing. They may also be struggling with emotional, behavioral, or academic challenges. Even if foster children do not have a specific diagnosis, they still have special needs in the sense that they require extra love, support, and patience. Foster parents need to be prepared to help their foster children heal from trauma. Two studies highlighted the need for increased training on foster children’s mental health issues, and parents want more advanced training to help them meet those needs (Kaasbøll et al., 2019).

Caseworkers in foster care also advocate for children, ensuring their rights are protected and that they receive the required services and support. In 2016, researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and Villanova University predicted that the number of states experiencing social worker shortages would jump from 20 to 38 by 2030, reaching a national shortfall of nearly 200,000 social workers (Lin et al., 2016). According to a federal center studying the child welfare workforce, that number may underestimate the shortage (Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development, 2020).

The issue of heavy caseloads has been a challenge for child welfare for decades and continues to impact children and families negatively. Data from the latest round of federal Child and Family Services Reviews (CFSRs) showed that caseloads negatively affected caseworkers’ ability to achieve permanence goals, respond promptly to maltreatment reports, efficiently file court documents and paperwork, and attend training (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services - Children’s Bureau, 2023).

Turnover among caseworkers continues to be a leading cause and consequence of heavy caseloads and workloads. The median caseworker handles 55 cases per year, but caseworkers stay on the job for a median of only 1.8 years (Edwards & Wildeman, 2018). When a caseworker quits, transfers, or leaves the role, the consequences are costly for families, whose cases may be reassigned and delayed; for agencies, which take on additional recruiting, interviewing, and training expenses; and for remaining caseworkers, who take on more cases. The support of faith-based programs becomes even more important in helping with these already overburdened and understaffed agencies. Faith-based programs boast higher levels of parent satisfaction and more efficient parent-agency communication than other agencies (Hodge et al., 2022). Many can also access a larger and more diversified pool of dedicated staff due to their partnerships with local congregations. One study published in the journal Children and Youth Services Review in 2018 found that faith-based adoption programs had significantly lower turnover rates than secular adoption programs. The study found that the average turnover rate for faith-based adoption programs was 15 percent, while the average turnover rate for secular adoption programs was 25 percent.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to reducing and managing caseloads. However, administrators can use a wide range of promising practices. Aside from more funding for staff positions and support, agencies can seek ways to support caseworkers and improve retention in a host of other ways. Effective training for new caseworkers is critical to retaining them. Ongoing training on trauma-informed care, effective communication, and conflict resolution would better equip caseworkers to navigate complex situations and build positive relationships with children and families. Regular and supportive supervision can also help caseworkers address challenges, promote professional growth, and contribute to job satisfaction. Ensuring staff have manageable caseloads to prevent burnout and allow for more focused attention on each case would also address the higher turnover rates. Bolstering partnering organizations, such as faith-based adoption centers, would help keep caseloads more evenly distributed.

Several states are implementing promising practices to reduce and manage caseloads and workloads for child welfare workers. Oregon has implemented several strategies, including:

- Creating a statewide system for tracking and monitoring caseloads. This allows Oregon to identify areas where caseloads are too high and take steps to address the problem.

- Developing a statewide caseload management plan, which includes hiring more caseworkers, providing more training, and streamlining workflows.

- Investing in evidence-based interventions. Oregon is investing in interventions that have been shown to reduce the need for child welfare services, such as home visiting and parenting programs.

- Collaborating with other agencies. Oregon is collaborating with schools and mental health providers to make more support available to children and families.

These strategies have helped Oregon reduce its child welfare worker turnover rate and improve caseload outcomes.

Private Adoption in America

Despite their historical prominence, private adoptions in America are facing a steep decline, plummeting by 24 percent from 2019 to 2020 alone (National Council for Adoption, 2023). This stark drop is surprising considering their past prevalence, and it raises a crucial question: Why are private adoptions underrepresented in adoption research? Several factors contribute to this underrepresentation. First, the private nature of the process itself makes data collection and analysis challenging. Unlike agency-facilitated or foster care adoptions, private placements often involve informal networks and legal agreements outside traditional reporting systems (National Council for Adoption, 2023). This lack of readily available data hinders researchers' ability to accurately assess trends, outcomes, and potential benefits or drawbacks of private adoptions. Additionally, the sensitive nature of the topic, particularly for birth mothers, can raise ethical concerns and deter researchers from pursuing studies that might unintentionally exploit or re-traumatize individuals involved in private adoptions (Brodzinsky & Schechter, 2008).

To improve access to private adoption research and potentially increase its utilization as a viable option for families and birth mothers, several solutions warrant consideration. Firstly, increased funding and support for longitudinal studies that ethically track long-term outcomes for children, birth mothers, and adoptive families involved in private adoptions can provide invaluable data and dispel existing myths or concerns (American Psychological Association, 2022). Secondly, collaborations between adoption agencies, researchers, and birth mother advocacy groups can foster trust and transparency, leading to the development of research protocols that are both informative and sensitive to the needs of all parties involved (Adoptions Together, 2023). Finally, promoting open communication and education about private adoption, including its benefits and challenges, can help address societal stigma and encourage individuals to consider this option when making informed decisions about unplanned pregnancies (Bartholow, 2018).

Faith-based programs present a unique opportunity to expand access and support for private adoptions in America. Leveraging their existing networks within diverse communities, these programs can offer crucial outreach and resources to pregnant women considering adoption who might not be reached by traditional channels (National Council for Adoption, 2023). By tailoring their approach to specific religious and cultural backgrounds, faith-based programs can provide culturally relevant support and combat the stigma often associated with unplanned pregnancy and adoption (Bartholow, 2018). This can create a more accepting environment for birth mothers and adoptive families, potentially encouraging more individuals to consider private adoption as a viable option.

Beyond outreach, faith-based programs can offer practical support through counseling and emotional guidance for birth mothers facing difficult decisions (Brodzinsky & Schechter, 2008). Financial assistance with pregnancy-related expenses, legal fees, and adoption costs can significantly alleviate stress and empower birth mothers to make informed choices. Additionally, providing material aid such as housing assistance and childcare resources can be crucial in facilitating successful adoptions (Adoptions Together, 2023).

Furthermore, faith-based programs can act as vital intermediaries, connecting pregnant women with potential adoptive families within their communities who share similar values and beliefs. This tailored approach can increase the likelihood of successful placements and foster long-term positive outcomes for all parties involved (National Council for Adoption, 2023). Open adoption support groups and resources can further strengthen these connections, allowing birth mothers and adoptive families to navigate ongoing relationships and maintain meaningful bonds (Adoptions Together, 2023).

Raising awareness within religious communities and offering educational resources can also encourage individuals to consider private adoption as a viable option when facing unplanned pregnancies (Bartholow, 2018). By addressing these challenges and leveraging their unique strengths, faith-based programs can play a significant role in expanding access to private adoption, providing comprehensive support to all involved, and ultimately contributing to positive long-term outcomes for children, birth mothers, and adoptive families.

Foster Care and Adoption Reform Efforts

During his tenure, President Trump took several steps to reform the foster care system in the U.S. In June 2020, he signed an executive order (EO) to strengthen the child welfare system that focused on three key areas: improving partnerships between state agencies and public, private, faith-based, and community organizations; improving resources for caregivers and those in care; and enhancing support for those aged out of the system. The order also sought to increase federal oversight of essential statutory child welfare requirements.

The first reform is aimed at creating robust partnerships between state agencies and public, private, faith-based, and community organizations. To accomplish this, the EO empowered HHS to do the following:

- Collect and publish localized data to aid in the development of community-based prevention and family support services and in the recruitment of foster and adoptive families,

- Hold states accountable for recruiting foster and adoptive families for all children;

- Develop guidance for states on best practices for effective partnering with faith-based and community organizations.

The importance of this reform cannot be overstated—empowering partnering organizations is the key to providing support to parents, caseworkers, and vulnerable children.

Leveraging data collected by agencies, such as HHS, aims to make informed decisions that improve the overall effectiveness and inclusivity of the foster care system. In this pursuit, the Biden Administration has been working to build upon and expand the groundwork laid by the Trump Administration, taking steps to refine and augment policies for the benefit of vulnerable children and families across the Nation. Some states have already begun to use the localized data that HHS has collected to develop community-based prevention and family support services and to recruit foster and adoptive families.

For example, California is using data to identify where the need for foster and adoptive families is greatest, then targeting recruitment efforts in these areas and developing new prevention and family support services where they are most needed.

Oregon is using the data to identify where caseloads are too high and to develop strategies to reduce them. The state is also using the data to track outcomes of children and families in the child welfare system and to identify where improvement is needed.

Other examples of how states are using data to improve child welfare include:

- Identifying children at risk of entering foster care. This information can then be used to target prevention services for these children and their families.

- Improving case management. States are using data to track caseloads and identify areas where caseworkers need more support.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of programs and services. This information can then be used to improve existing programs and develop new ones that meet the needs of children and families.

The second reform seeks to improve resources provided to caregivers and those in care. This includes increased educational options, trauma-informed training, and access to financial help.

The third reform aims to improve federal oversight of essential statutory child welfare requirements. To accomplish this, the EO required Title IV-E reviews and the Child and Family Services Reviews to strengthen the assessments of critical requirements. It directs HHS to guide states on flexibility in using federal funds to support and encourage high-quality legal representation for parents and children. This EO can be extrapolated for future legislation and community efforts.

In addition to the executive order reform ideas, other reform ideas include education support, including expanding access to high-quality early childhood education. This could include free or reduced-cost preschool for all foster children and expanding access to other quality early childhood programs that parents agree are a good fit for the child. Providing more academic support for students in foster care could include tutoring and mentoring, as well as financial assistance for college and other post-secondary education. State policymakers should consider how to make it easier for youth who have aged out of foster care to attend college, which could include tuition waivers, other financial assistance, and academic support services.

Another area of reform that could help improve the foster care system is providing trauma-informed training for all involved in the system. Providing trauma-informed training to all child welfare professionals would help them understand the impact of trauma on children and families and develop trauma-informed practices. Additionally, providing trauma-informed training to foster parents and other caregivers would help them understand the impact of trauma on the children in their care and develop trauma-informed parenting practices. In all, providing trauma-informed training to schools and other community organizations would help them create a supportive environment for children and families.

Lastly, Increasing the financial assistance available to foster families and other caregivers would help to ensure they had the resources needed to provide for the children in their care. This financial assistance to youth who have aged out of foster care could be used to help them pay for rent, food, and other expenses as they transition to adulthood. Creating a fund to help children in foster care pay for college and other post-secondary education would help youth achieve their educational goals and break the cycle of poverty.

These are just a few ideas for how to improve the resources provided to caregivers and those in care. By implementing these reforms, we can help to ensure that all children have the opportunity to reach their full potential.

The Trump Administration also created the “All in Foster Adoption” campaign launched by HHS. This campaign recognizes the urgent need to find permanent, loving homes for the thousands of children waiting to be adopted. By highlighting the stories of successful foster adoptions and providing resources and support to prospective adoptive parents, the campaign seeks to remove barriers and dispel misconceptions surrounding foster care and adoption. Through targeted outreach efforts, the campaign strives to create a culture of adoption and encourage individuals and families to consider opening their hearts and homes to children in need. The All in for Foster Adoption data revealed that between October 1, 2019, and March 31, 2020, 28,554 children and youth were adopted nationwide (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, n.d.).

Policy Guidance for States

States can play an important role in strengthening foster care systems. This section outlines some approaches states can take on the most critical issues.

Protect Religious Liberty of Faith-Based Foster Care and Adoption Providers

Faith-based organizations play a critical role in supporting foster care and the well-being of needy children, and states can help protect and strengthen these groups. Faith-based groups’ partnerships with churches could include organizing donation drives for essential items, hosting adoption and foster care awareness events, or providing mentorship programs for older foster youth. By leveraging their resources, compassion, and community networks, they can provide help in the following ways:

- Respite. One key is providing respite care for foster families, which gives foster parents a break to recharge and take care of their own needs. Faith-based organizations could set up volunteers to take turns caring for foster children for a few hours or overnight.

- Support groups. Support groups for foster parents and youth can provide both with a chance to connect with others going through similar experiences.

- Financial help. Faith-based organizations could raise money to provide financial assistance to foster families and foster youth who need it to help pay for living or educational expenses or other needs.

- Advocacy. Faith-based organizations can advocate for policies that make it easier for people to become foster parents, that provide more support to foster families, and that improve the child welfare system overall.

In addition to the above policy activities, faith-based organizations can support foster care and the well-being of needy children by:

- Educating their congregations about the needs of foster children and families and encouraging people to get involved in supporting foster care.

- Recruiting people from congregations to become foster parents or mentors to foster youth.

- Organizing volunteers to help at child welfare organizations with activities such as sorting donations, packing care packages, or spending time with foster children.

Faith leaders have access to many families through their partner congregations. Many faith-based groups are supporting foster families, including the CALL faith-based group in Arkansas. This organization has recruited about 50 percent of the foster families serving in the state. The organization now serves children nationwide and helps with the placement process in adoptive homes.

It is important that states establish religious exemption laws and fight the Biden Administration’s decision to revoke Trump-era protections, as they have done in several states. States should pass laws to protect religious liberties and request approval from HHS, allowing child placement agencies to adhere to their religious convictions. Ten states have already established such policies, and Alabama’s Child Placing Agency Inclusion Act provides a solid blueprint for other states to follow. These religious exemption laws do not exist to discriminate against LGBTQ couples but to ensure that all families are considered equally. We must resist Biden’s effort to rescind them, as it could cost us vital adoption opportunities. Continuing to take away pre-approved waivers and refusing to approve new ones from other states will only harm foster children and rob them of resources, particularly those with special needs who are often prioritized by faith-based organizations.

Implement Expanded Adoption Tax Credits for Foster Families

Adopting a child is one of the most important decisions one might make in a lifetime. However, the cost is high and could be prohibitive without assistance. The federal government offers a tax credit of up to $15,950 per adopted child under age 10.

Some states offer a state tax credit or tax deductions for citizens and increase incentives for families to adopt children who are in foster care or who have a disability. For example, in 2018, Illinois created a tax credit with a maximum of $2,000 per eligible child or $5,000 per eligible child who is at least one year old and a resident of the state at the time of adoption. Idaho established a deduction for legal and medical expenses associated with adoption, with a maximum deduction of $10,000 for adoptions in taxable years beginning after 2017. Iowa expanded its existing adoption tax credit from $2,500 to $5,000. A list of states offering tax credits can be found here.

A recent study published in the journal Child Welfare in 2022 examined the impact of the federal adoption tax credit on the number of children adopted from foster care. It found that the tax credit increased the number of children adopted from foster care by an average of 7 percent per year. The study also found that the adoption tax credit had a greater impact on the number of children adopted from foster care in states with higher rates of foster care. The study's authors concluded that the adoption tax credit is an effective way to increase the number of children adopted from foster care. The authors also recommended that the federal government increase the amount of the adoption tax credit and make it more accessible to adoptive families (Brown, 2022).

Support Organizations that Aim to Decrease the Number of Children Entering Foster Care

While it is important to implement reforms for children already in foster care, states must also decrease the number of children in foster care by aiding families in crisis and preventing more children from entering the system long-term. Technology is one way to do this. A private portal called CarePortal has had good success with a private sector–driven model to support at-risk foster youth across the country. The platform allows struggling families and children to connect with nearby churches that can provide help. Agencies upload details about a family’s urgent needs, and then an alert goes out to the community in real time. This allows for community and resource support that can prevent children from having to go into foster care. Between 2015 and 2022, 224,350 people were served by CarePortal (CarePortal, 2022). States should encourage the use of this platform, promote it to families in crisis, and encourage similar entities to form.

Better Support Foster Parents

To better support foster parents, it is crucial to implement policies that address their unique needs and challenges. One policy recommendation is establishing comprehensive training and support programs. This support would include pre-placement training to equip foster parents with the necessary skills and knowledge to care for children with diverse backgrounds and experiences. Ongoing training should also address foster children's evolving needs and help foster parents navigate complex issues such as trauma-informed care and behavioral management. Agencies should also ensure that foster parents have access to a robust support network, including regular support groups, respite care options, and access to existing mental health services. Most foster care agencies offer mental health support and training to foster parents. This may include individual counseling, group therapy, and workshops on topics such as trauma-informed care and behavior management. Many foster parents are able to access mental health services through their local community mental health centers or private providers. These services may include individual therapy, family therapy, and medication management. A number of online resources offer mental health support and training to foster parents. These may include articles, videos, and webinars on topics such as trauma-informed care, self-care, and parenting challenging behaviors.

Agencies can help ensure that training sessions for prospective and current foster parents are helpful and that the time required for training is manageable. Making training more accessible by providing online training options and requiring fewer sessions would help (Adopt US Kids, 2020).

Temporary foster families ultimately adopt fifty percent of foster children. To help ease the process for these families, offering dual licensing for people interested in both foster parenting and adoption would help reduce redundancy.

Improve Mental and Behavioral Healthcare

While increasing support and providing needed resources for foster parents will indirectly help address the mental health needs of children, more steps are needed to improve mental health. Currently, frequent placement transitions and health insurance issues can make it difficult for foster children to receive consistent care for issues such as anxiety and PTSD. Healthcare professionals should conduct formal assessments of mental health when a child enters foster care and while the child remains in the system. Periodic screenings would allow foster children to receive timely treatment (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021). They would also help address issues that may arise during transitions when children enter new foster homes.

Thankfully, there has been a surge in state-level trauma-informed care legislation over the last five years. These bills and statutes promote many trauma-informed practices to help address the needs of foster children. Practices include screening for childhood trauma, training staff to address it, creating supportive environments, and providing appropriate healthcare. Many bills also emphasize education, early childhood, and behavioral health. One example is Public Act 099-0927 in Illinois, which passed in January of 2017. It requires that, in addition to physical health screenings, social and emotional screenings be part of school entry examinations. Another example is the Brighter Minds Initiative in Wisconsin, which recently passed and provides increased funding for public agencies and non-profits in select counties to reduce instances of childhood trauma (Maul, n.d.). Other states should follow suit and pass similar trauma-informed care legislation.

Review and Eliminate Burdensome Regulations

Keeping foster children safe while they are in care is essential, but some requirements for parents and home safety standards exceed what is needed.

While agencies must ensure that a foster child is placed in a safe physical dwelling, some state requirements related to this goal exceed federal requirements and create unnecessary barriers. Examples include:

- Income requirements: Some states have income requirements that can prevent qualified people from becoming foster parents. All states require that foster parents have a stable and verifiable source of income to meet their family’s needs, and some have specific requirements for foster parents caring for children with special needs. In California, for example, foster parents caring for children with special needs must have a minimum annual income of $45,000. In addition to the financial burden, income requirements can also create a logistical burden for potential foster parents. The process of verifying income can be time-consuming and complex, and it may require foster parents to submit extensive documentation. This can discourage people from pursuing foster care, even if they are qualified and motivated. Some states may also have other requirements—for example, requiring that foster parents have a certain amount of home equity or that they own their own home.

- Criminal background checks: Some states have criminal background check requirements for foster parents that are more stringent than the requirements for other types of caregivers, such as biological childcare providers such as aunts or uncles.

- Home safety standards: Some states have home safety standards for foster parents that are more stringent than the standards for biological parents. For example, some states require foster parents to have a fenced-in yard, even if they live in a safe neighborhood.

- Age: Some states have age requirements for foster parents, such as requiring foster parents to be between the ages of 21 and 55. This can exclude qualified people, such as retirees who may have more time to devote to fostering, from becoming foster parents.

States should re-evaluate their foster care standards and eliminate unnecessary barriers that hinder the recruitment and retention of qualified foster parents. This includes revisiting income requirements, streamlining documentation processes, revising background check procedures, and prioritizing access to support resources for foster parents. Adopting a flexible approach to setting standards, informed by national model guidelines, can ensure a consistent quality of care while acknowledging specific state needs.

By removing these unnecessary hurdles and providing adequate support, we can create a more accessible and effective foster care system that serves the best interests of children in need.

Improve Communication Between Agencies and Foster Parents

Foster care agencies have oversight in providing safe and stable homes for children who need them and should have supportive relationships with foster parents. Recent research revealed that 35 percent of licensed foster parent homes never have a child live with them, and currently, the recruitment strategies used by state agencies are minimal (Hayes, 2020). Some foster parents choose to decline placements due to mismatched needs, personal situations, or discouragement from a lack of support. Additionally, current recruitment strategies by state agencies may be inadequate, leading to limited awareness among potential foster parents. Furthermore, rigid requirements and inflexible systems can disproportionately exclude qualified individuals from becoming foster parents. Inefficient matching processes and a lack of support for foster parents further contribute to the issue, leading to placement failures and discouraged foster parents.

A multi-pronged approach is essential to address these challenges. Improved recruitment strategies targeting diverse populations and emphasizing the need are crucial. Reviewing and adjusting eligibility requirements to ensure fairness and inclusivity is also necessary. Enhancing the matching process through comprehensive assessments can create optimal pairings between children and foster families. Additionally, providing financial assistance, training, and ongoing support to foster parents is vital for their success. Finally, fostering better communication and collaboration between agencies and foster parents can address concerns and improve the overall foster care experience. A strategic plan with targeted recruitment could improve the likelihood of obtaining individuals who genuinely want to be foster parents.

Improving the matching process between foster parents and foster children is necessary to form successful parent-child relationships. The Denver Department of Human Services developed a website to inform prospective foster parents about children needing care. The agency found that the website was an effective recruiting tool and that families recruited through the website were more likely to follow through with the licensing process. The information provided ahead of time through the website was more helpful than the previously used pamphlets and classes (Myslewicz & Yeh García, 2014). Other states should create websites with similar missions.

It is also important to strengthen communication between agencies and foster parents (Courtney & Brown, 2023). Parents know what these children need and, if given the opportunity, can provide significant insight for case planning, court proceedings, and activities and interests of the children. A 2014 study found that more frequent interaction between the foster parent and the foster care agency improved services for children (Myslewicz & Yeh García, 2014). By neglecting to tap into the knowledge held by foster parents, agencies are failing children. Every child has unique needs and craves unique parenting.

Improve Data Systems

Robust data systems could significantly improve the foster care system by providing accurate, real time information about children in care, their needs, and their progress. Strong data can help social workers and other professionals make more informed decisions about placements, services, and interventions. For example, data could reveal patterns about what types of placements lead to the best outcomes for different types of children or which services are most effective in addressing specific needs. Data systems also could help track and reduce disparities, such as racial disparities in placement stability or educational outcomes. They could improve accountability by making it easier to monitor the performance of foster care agencies and providers.

In Tennessee, the Department of Children’s Services (DCS) uses a matching process to connect foster children with prospective adoptive parents. The primary tool for this is the Tennessee Adoption Exchange (TAE), an online database that allows prospective adoptive parents to create profiles and search for children available for adoption. The TAE database contains information about waiting children, including their age, background, interests, and any specific needs or requirements. Prospective adoptive parents can search the database using various criteria to find children who may be a good match for their family. Once a potential match is identified, the DCS facilitates the process by providing additional information, conducting home studies, and coordinating meetings between the prospective adoptive parents and the child. The goal is to ensure a suitable and compatible match between the child and the prospective adoptive family. The process is guided by state laws, regulations, and the expertise of adoption professionals involved in the placement process.

The June 2020 executive order issued by President Trump requires that the HHS secretary “develop a more rigorous and systematic approach to collecting state administrative data as part of the Child and Family Services Review.” The executive order recommends collecting data on the average retention rate of foster parents, the number of families available to foster, and the time it takes to complete foster care certification. The federal Child and Family Services Review should also assess the number of foster parents who become licensed and the percentage of foster homes in which children are placed.

States should develop the capability to track the capacity, location, and licensure status of all public and private foster homes in real time. This data could be used to target foster home recruitment efforts and to identify placement options quickly. Agencies must assess the needs of foster parents using a standardized data collection mechanism.

Efforts to reform foster care have burdened agencies and caseworkers with ever-increasing compliance-related activities monitored by multiple layers of oversight. However, mandates should not be created just for the sake of having rules. They should be supported by clear evidence that following them will lead to tangible improvements in the lives of children. This evidence should be based on reliable research and data demonstrating the positive effects of these mandates on various aspects of child well-being, such as physical health, mental health, emotional development, and educational outcomes.

Conclusion

Improving the foster care and adoption systems in the U.S. requires a comprehensive approach that addresses the challenges faced by foster and adoptive parents, reduces placement instability, bolsters religious freedom, and strengthens the transition to adulthood for foster youth. By implementing the proposed solutions, we can create a more supportive and nurturing environment for children in foster care, ultimately improving their well-being and prospects. Foster care is a far-reaching intervention in the lives of particularly vulnerable children who deserve consideration of their personal needs, not homogenization and dismissal.

State and local foster care systems, partnering faith-based organizations, and families should be set up for success. Reform is needed to address funding issues, reduce regulations, improve communication, and protect religious liberty. Coupled with a willingness among policymakers to generate and employ evidence on best practices, foster care research is poised to inform these policy reforms and improve the welfare of children.

An urgent imperative exists for reform within the U.S. foster care system. The current framework frequently falls short in addressing the needs of the children under its care, resulting in unfavorable outcomes for children’s education, mental health, and long-term stability. This transformation must encompass multiple goals, including expanding tax credits, strengthening support for foster parents, enhancing foster parent training, safeguarding the religious liberty of faith-based foster care and adoption providers, optimizing agency and foster parent communication, and continuing to build data systems. It is vital to reform foster care because every child deserves a safe, supportive environment that fosters their well-being, development, and future success.

[1] The turnover rate for foster parents is calculated by dividing the number of foster parents who leave the system in a given period of time by the total number of foster parents at the beginning of that period of time. For example, if there are 100 foster parents at the beginning of a year and 50 of those foster parents leave the system during the year, then the turnover rate for foster parents would be 50 percent. The turnover rate for foster parents is an important metric to track because it can provide insights into the challenges that foster parents are facing and the areas where they need more support.

Resources