The Pitfalls of Same-Day Registration

Key Takeaways

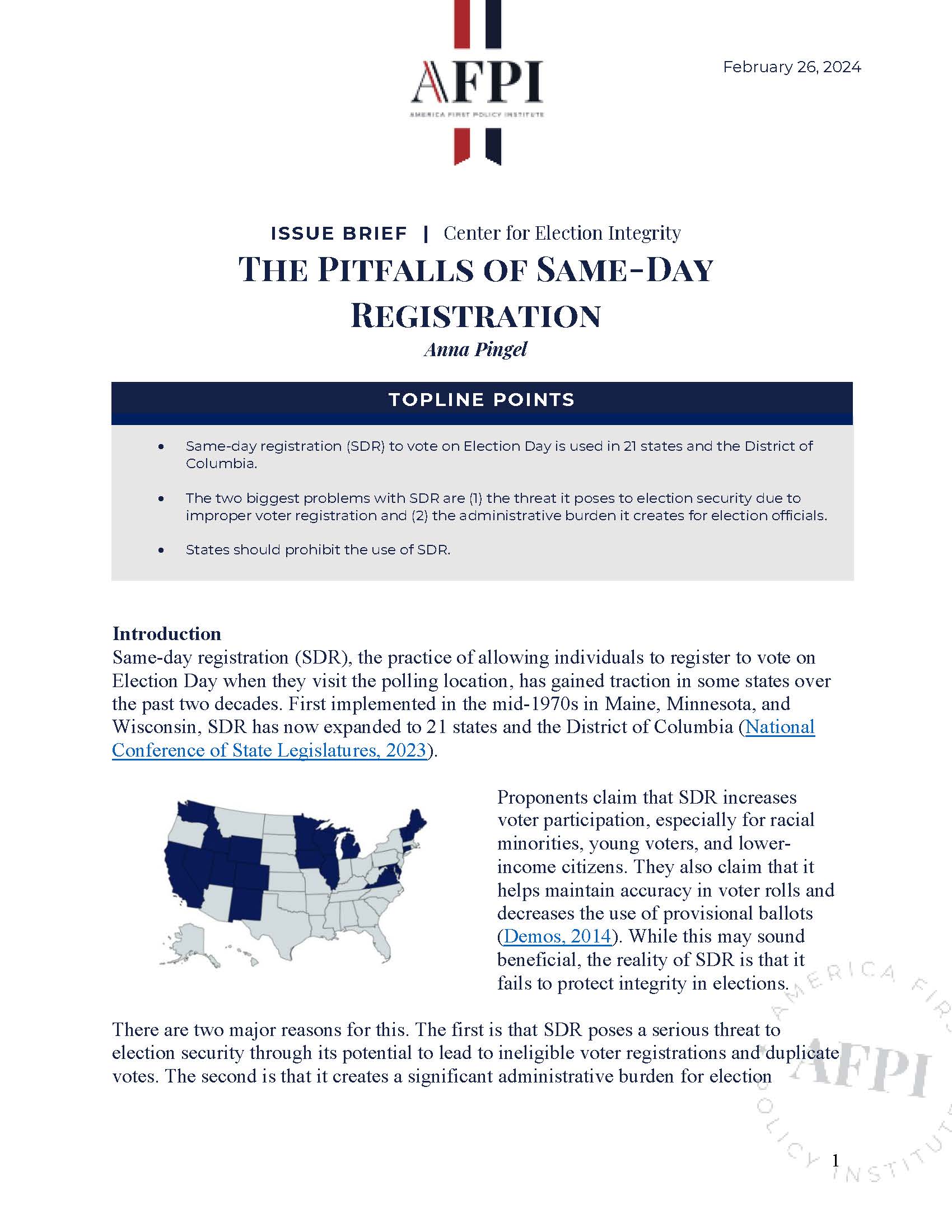

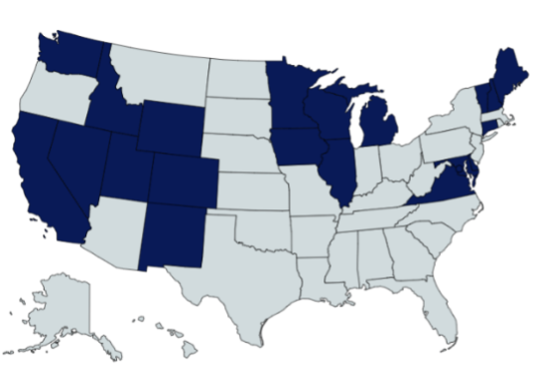

Same-day registration (SDR) to vote on Election Day is used in 21 states and the District of Columbia.

The two biggest problems with SDR are (1) the threat it poses to election security due to improper voter registration and (2) the administrative burden it creates for election officials.

States should prohibit the use of SDR.

Introduction

Same-day registration (SDR), the practice of allowing individuals to register to vote on Election Day when they visit the polling location, has gained traction in some states over the past two decades. First implemented in the mid-1970s in Maine, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, SDR has now expanded to 21 states and the District of Columbia (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023).

Proponents claim that SDR increases voter participation, especially for racial minorities, young voters, and lower-income citizens. They also claim that it helps maintain accuracy in voter rolls and decreases the use of provisional ballots (Demos, 2014). While this may sound beneficial, the reality of SDR is that it fails to protect integrity in elections.

There are two major reasons for this. The first is that SDR poses a serious threat to election security through its potential to lead to ineligible voter registrations and duplicate votes. The second is that it creates a significant administrative burden for election officials on the very day their services are most strained. Both of these problems mean that SDR jeopardizes the integrity of elections.

SDR’s Effect on Voter Registrations and Duplicate Voting

A major concern with SDR is the elimination of comprehensive voter identification verification. Because SDR affords election officials limited time to check voter eligibility, the risk of accepting votes from ineligible voters increases greatly. Without the time necessary to check if a voter actually lives within the district in which that person is voting, there is no way to be certain that fraudulent votes are not being cast. Once elections are certified, which, at most, happens only a few weeks after the election, votes cannot be discarded or marked as fraudulent.

North Carolina serves as a clear case study. In 2007, the state legislature enacted SDR after heated debate. Following the 2008 election, in which SDR was used, several North Carolina counties voiced concerns after meeting at the request of the Board of Elections to review their experiences with and perspectives on SDR. One county noted “numerous undeliverable voter registration cards returned after the canvass timeframe, which allowed the voter’s vote to count and it should not have” (Civitas Institute, n.d.). This means that the county could not verify the voter’s address and, therefore, the voter’s eligibility, yet these votes were counted due to SDR. The subsequent report issued by the Board of Elections reluctantly noted that multiple county boards were in the same situation of having counted ballots cast by voters whose eligibility could not be verified. The report then praised the increased voter turnout and generally dismissed the concerns raised by the counties (Bartlett, 2009).

However, it is not equitable to hold one set of voters (those who register before the election and whose addresses and eligibility are verified) to a different standard than another set of voters (those who register on Election Day and whose addresses and eligibility are not verified). According to the 2022 Election Administration and Voting Survey 2022 Comprehensive Report, 26 percent of voter roll removals in 2022 resulted from a cross-jurisdiction change of address (Election Assistance Commission, 2023). This was the category of reasons for removal that showed the highest percentage, reflecting the fact that incorrect addresses are the most common reason for ineligibility.

SDR also creates a vulnerability in the election process by opening the door to duplicate voting. If an individual registers in the morning in one county and then votes, that person could later drive to multiple neighboring counties throughout Election Day, register again, and vote multiple times. Without immediate verification of that person’s address, it would not be possible to stop this from happening. The same 2009 report from North Carolina noted that “[t]here were issues with some voters who submitted a voter registration application to one county during the last few weeks before the registration deadline and then appeared to vote in another county or actually registered at a one-stop site in another county and voted. Similarly, there were voters who registered at a one-stop site and voted although they had been issued a mail-in absentee ballot in a previous county of registration” (Bartlett, 2009). This could especially become an issue in high-mobility states and those with large universities, where yearly influxes of students can change the voting population dynamics. This vulnerability must be prevented by eliminating SDR, particularly in local races where only a handful of votes can decide elections.

Some states have counties where the number of registered voters exceeds the voting-age population of that county. In Michigan, for example, which uses SDR, every county except three with a voting-age population of more than 50,000 people has a registration rate of over 100 percent (Michigan Department of State, 2023; United States Census Bureau, 2023). Multiple entities have filed lawsuits, not only in Michigan but in other states, claiming that these impossible voter registration rates violate the National Voter Registration Act. SDR exacerbates this by further bloating the voter rolls without proper eligibility checks. Then, once someone is on the voter roll—unless that person is deceased or otherwise ineligible under state law—that person cannot be legally removed under federal law until two mailers have been sent with no affirmation of eligibility and until after two federal election cycles (four years). Given that it is so difficult and time-consuming to remove names from voter rolls, it is incumbent upon states to ensure that names being entered onto voter rolls belong to eligible voters.

SDR’s Burden on Election Administrators and Workers

In a straightforward editorial, a Massachusetts town clerk writes: “As a town clerk, one of my primary responsibilities is to administer elections and I strongly believe that same-day voter registration is bad public policy. I refute the notion that voter registration deadlines are somehow ‘arbitrary’ and unconstitutional…they ensure election officials can conduct fair, accurate and orderly elections” (White, 2017).

SDR makes it more difficult for election workers to estimate how much ballot paper and how many workers will be needed at each polling location. The existing voter rolls provide some insight into this with an estimated turnout by precinct. If the voter rolls are not the guide, it is hard to estimate. Election workers are already incredibly busy on Election Day and do not need additional stress or uncertainty imposed on them. The administrative burden produced by SDR jeopardizes the goal of efficient, accurate elections.

Recommendations

State lawmakers should prohibit SDR in their states and resist efforts from proponents who wish to enact it.

Conclusion

SDR is not necessary for voters to be able to vote freely and easily. The removal of real barriers, such as poll taxes, race- or gender-based prohibitions, and land ownership requirements are long gone. Voting has never been easier or more accessible. The top reasons that Americans do not vote are that they are not interested in the process or the candidates, they are too busy, they have an illness or disability, or they are out of town—not that there are extreme barriers to voting itself.

SDR is a solution in search of a problem. It can open the door wide for ineligible individuals to register and even to cast duplicate votes. It can also negatively affect the ability of election officials to do their jobs on Election Day. Americans need to be able to trust that election laws do not inadvertently create situations in which their votes can be diluted. SDR does not align with the principle of making it easy to vote but hard to cheat because it clearly opens opportunities for cheating. For this reason, lawmakers should prohibit SDR in the interest of protecting every eligible vote and every eligible voter.

BIOGRAPHIES

Anna Pingel is the policy analyst for the Center for Election Integrity at the America First Policy Institute

Resources