Middlemen Favor Unaffordable Prescription Drugs

Key Takeaways

Over the past 10 years, Americans have spent increasingly more on expensive brand-name prescription drugs.

A major reason drugs are becoming more expensive for families is that drug manufacturers compensate pharmacy benefit managers for favoring high-cost brand-name drugs at the expense of more affordable generic drugs. In addition, the Affordable Care Act incentivized insurers to merge with PBMs and spend more on prescription drugs.

Policymakers can make prescription drugs more affordable by increasing transparency, requiring PBMs to operate with a fiduciary responsibility, and ending perverse incentives that encourage PBMs to spend more on prescription drugs.

Overview

Americans rely on commercial and government health plans and payers to manage their drug benefits responsibly, ensuring that they receive the highest quality drugs at the lowest possible cost. These plans, often sponsored by employers or unions, contract with companies known as pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to design drug benefits for their members. However, PBMs often exploit their position as middlemen to enrich themselves at the financial expense of health plans and, ultimately, patients.

Patients need PBMs to work on their financial and clinical behalf. Lawmakers should implement reforms ensuring PBMs deliver value to patients and health plans. These reforms should include increasing transparency between PBMs and their clients, designating PBMs as fiduciaries when they work for health plans, and ending perverse incentives that encourage PBM consolidation.

Drugs Are Increasingly Unaffordable

Over the past several years, America’s patients, taxpayers, and employers have been spending significantly more on prescription drugs, especially brand-name drugs. Between 2011 and 2021, America’s annual spending on retail prescription drugs increased from $256.3 billion to $374.5 billion (CMS, 2022). In fact, the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation’s (ASPE) most recent report concluded that the increase across all drug spending was driven by “increases in spending per prescription, and less so by increases in the number of prescriptions” (ASPE, 2022). In 2021, spending on brand-name drugs accounted for 80 percent of spending on both retail and non-retail prescription drugs.

Prescription drugs account for 22 percent of the cost of commercial health insurance premiums (AHIP, 2022). Due to the cost of drugs, Americans are struggling to afford the medicine they need. Last year, one in 10 Medicare beneficiaries indicated they did not fill a physician’s prescription because they could not afford it (Dusetzina et al., 2023).

Over the next several years, Americans are expected to pay even more for retail prescription drugs. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimates that the total cost of retail drugs in the U.S. will grow from $388 billion in 2020 to $609 billion by 2030, a 57 percent increase (Roehig & Turner, 2022).

What Are PBMs?

When an individual enrolls in commercial health insurance, the health insurer administers the individual’s benefits by managing networks of hospitals and clinics, processing claims, and negotiating with providers to determine the prices of health care services. However, health plans contract with other companies, known as PBMs, to manage the prescription drug benefits within each health plan. These services include creating pharmacy networks, processing pharmacy claims, and negotiating the price of prescription drugs with drug manufacturers.

PBM negotiations determine how much the health plan will pay for a drug and how much the plan’s members will pay for the drug through copays and coinsurance. PBMs do this, in part, by using formularies. The formulary, as set by the PBM and the health plan, directs the plan’s members to purchase some drugs and avoid others. When the PBM places a drug at the top of its formulary, patients will often pay lower cost-sharing for that drug, and the plan will pay a greater share. When the PBM places drugs lower on their formulary, patients will often pay higher cost-sharing for the drug and can also often face utilization management hurdles, such as prior authorization and step therapy, because it is not the preferred drug of the health plan.

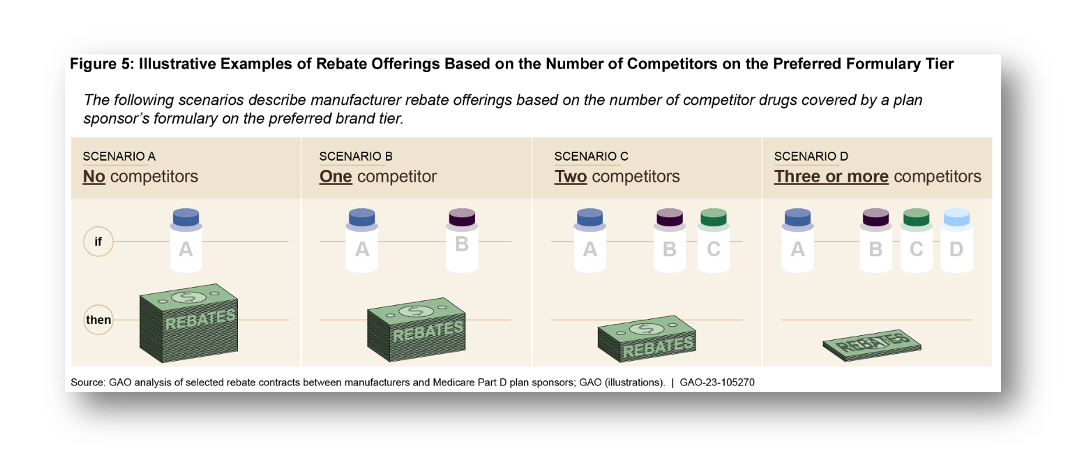

PBMs manage formularies for thousands of employer health plans and negotiate with hundreds of drug manufacturers about where they place their drugs on employers’ formularies. When PBMs negotiate with drug manufacturers, the manufacturers will offer the PBM a payment, known as a rebate, in exchange for meeting certain terms of the rebate contract. For example, to receive the rebate, the PBM must ensure that the beneficiaries of an employer’s health plan purchase a certain amount of the drug being negotiated. This is often accomplished by the PBM placing the drug on a high tier of its formulary, which will lower the patient cost-sharing for the drug and, in turn, encourage the plan’s members to purchase it over other drugs. Rebates can also encourage PBMs to restrict access to drugs that compete with the drug manufacturer offering the rebate because the rebate is tied to plan beneficiaries using a certain volume of the preferred drug.

PBMs generate a significant amount of revenue from rebates. Contractual agreements between PBMs and health plans are often structured so that PBMs retain a percentage of the rebates they receive from drug manufacturers. This incentivizes PBMs to seek greater rebates on behalf of the health plan but can also incentivize PBMs to keep a larger percentage of the rebate. Separate analyses by the Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew Trusts, 2019) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) (GAO, 2019) found that PBMs passed more than 90 percent of rebates back to health plans in 2016. However, recent investigations have found that the three largest PBMs use complex arrangements with their group purchasing organizations (GPOs) to retain rebate revenue not disclosed to the health plan (FTC, 2024).

PBM Incentives Harm Patients

The perverse incentives in the PBM industry contribute to the reasons Americans spend increasingly more on prescription drugs. Employers and health plans pay PBMs to design drug benefits so members can access high-quality drugs at the lowest possible cost. However, PBMs are incentivized to demand larger rebates from drug manufacturers to maximize their earnings. In return, pharmaceutical manufacturers are incentivized to increase the rebate provided on a drug as they bargain with PBMs for preferred formulary placement. This negotiation process often encourages manufacturers to artificially increase list prices to generate greater rebates as they negotiate with PBMs. One analysis of 13 manufacturers found that their net revenue[1] grew each year by an average of 2.9 percent. Rebates and other payments to PBMs, however, increased each year by an average of 13.5 percent. This means the growth in the gross revenue was primarily due to the growth in rebate payments, not an increase in net revenue.

In addition, the analysis found that 40 percent of the list price of drugs was devoted to payments to PBMs in 2019, meaning patients paid higher prices largely because rebates grew. This perverse incentive hurts patients. If a patient has not met a deductible and must pay the full list cost of the drug, this means the patient is paying 40 percent of the cost of the drug to the PBM (Weinstein & Schulman, 2020).

Rebates also increase costs for patients because they come with legal agreements that require PBMs to steer patients to more expensive medications. A 2023 report by the GAO found that brand-name drug manufacturers established legal agreements with PBMs that manage Medicare’s drug benefit program, Part D, to ensure that the PBM favored their drug at the expense of cheaper generic versions (GAO, 2023). In fact, for some highly rebated drugs, the health plan paid less for the drug than the patient did.

First, the GAO found drug manufacturers paid PBMs higher rebates if the manufacturer’s drug was placed in a more favorable formulary tier than their competitor’s drug. Second, they paid higher rebates if the PBM placed fewer competing drugs on the same tier as the manufacturer’s brand-name drug. Third, they paid higher rebates if the PBM did not impose utilization controls, such as prior authorization and step therapy, on the manufacturer’s brand-name drug. And fourth, they paid higher rebates if the PBM imposed more utilization restrictions on their generic competitors.

As a result of these rebate agreements, PBMs have placed brand-name drugs on a more favorable tier of their formularies at the expense of generics. A 2019 analysis of Part D plans found that 72 percent of PBM formularies placed at least one brand-name drug in a lower cost-sharing tier than its cheaper generic counterparts (Socal, Bai, & Anderson, 2019). This analysis also found that 30 percent of Part D formularies imposed utilization controls less frequently on at least one brand-name drug when compared to its generic version.

Over time, the formularies of many PBMs have become less favorable to more affordable generics. In 2010, PBMs for Part D plans placed 73 percent of generic versions of brand-name drugs on the lowest cost-sharing tier of their formularies (Feldman, 2021). However, by 2017, PBMs reduced the share of generics in their lowest cost-sharing tier to 28 percent. This increased the average copay for a generic prescription in Part D plans from $11 to $33, tripling the average cost in just seven years.

The rebate agreements that drug manufacturers establish with PBMs incentivize these companies to administer drug benefits in a fashion that increases spending on prescription drugs, which can lead to higher premiums and greater cost-sharing for patients. A 2022 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office found that the net price, after accounting for rebates, of the average brand-name drug prescription in Part D increased from $149 to $353 between 2009 and 2018, a 136 percent increase (CBO, 2022).

To address the perverse incentives of rebates, the Trump Administration finalized a new regulation in 2020 to require PBMs that operate in the Part D program to pass along manufacturer rebates directly to the patient (42 C.F.R. 1001, 2020). Debate on the effects of the proposal centered around whether seniors’ premiums in Part D would increase: Some actuarial projections indicated premiums would rise, while the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) publicly confirmed that the policy would not result in increased beneficiary premiums, out-of-pocket costs for patients, or federal spending (Sachs, 2020). In 2022, Democrats rescinded this policy through the Inflation Reduction Act (Cubanski, Neuman, & Freed, 2023).

Spread Pricing Increases Drug Spending

Another PBM practice that increases drug costs is known as spread pricing. When a patient fills a prescription at a pharmacy, the patient’s health plan, including Medicare Part D and Medicaid, pays the PBM the cost of the drug so that the PBM can reimburse the pharmacy for the prescription. However, PBMs will often reimburse the pharmacy that dispenses a drug just a fraction of the amount the plan paid them. The PBM keeps the difference, the “spread,” as profit. This practice encourages PBMs to charge health plans a higher price than they actually paid to the pharmacy. A report by Ohio’s state auditor found that PBMs retained nearly $225 million in profits from the state’s Medicaid Managed Care Organization (MCO) program from spread pricing in 2017 (Ohio, 2018). Another report found that PBMs managing Kentucky’s Medicaid MCOs charged taxpayers $123 million in spread pricing in 2018 (Kentucky, 2019).

Spread pricing can also hurt patients. If a patient has not yet met a deductible, the patient is often required to pay the list price of the drug, which includes the spread amount. For this reason, several states have acted to address spread pricing and its effect on patients. As of 2019, 11 states have instituted some prohibitions on spread pricing in MCO contracts (KFF, 2019). Other states allow pharmacists to inform the patient of the lowest cost of the drug purchased with cash, which excludes the spread cost (GAO, 2024).

PBMs Need Transparency

One reason that PBMs can operate against the interests of patients, employers, and federal payers is that employers and payers often lack the information they need to hold the PBM accountable. In general, PBMs do not disclose to employers and payers an itemized receipt of claims data, rebate amounts for drugs on their formulary, an explanation of why they included certain drugs in their formulary but excluded less expensive alternatives, or other relevant information (Barlas, 2015). To obtain this information, employers must pay between $15,000 and $200,000 to audit the PBM (Barlas, 2015). This lack of transparency makes it impossible for employers to compare their PBM’s performance to the performance of alternative PBMs or to shop around for more competitively priced options. Employers and unions are trusted to make the best decisions on behalf of their employees, and without detailed pricing and claims data, they are left to blindly trust that the PBM is working in their best interest.

Greater transparency would help employers determine if their PBM was designing their drug benefit in their best interests—namely, to obtain the highest-quality drug at the lowest possible price for their employees. These measures would also give employers actionable information to demand that their PBM change their drug benefit program to serve their employees better. After a health plan within the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program instituted transparency measures for their pharmacy spending, they learned that their PBM, Express Scripts, overcharged them by $45 million for the costs of prescription drugs (OPM, 2024).

President Trump signed into law several proposals that empower the federal government to require PBMs to provide greater transparency to employers and patients through the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) of 2021 (2020). The law prohibits gag clauses in contracts between PBMs, insurers, and employers, which had kept employers from accessing their medical and pharmacy claims data. The law also requires PBMs and other service providers to make standard disclosures to the employer, such as the description of the services they anticipate providing to the employer or any indirect compensation that might present a conflict of interest. Yet neither HHS nor the Department of Labor (DOL) have meaningfully enforced these provisions of the CAA.

Other federal laws on the books could also be used to increase transparency. The Trump Administration used authority from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) to promulgate the “Transparency in Coverage” rule, which requires health plans and payers to provide extensive price and cost-sharing information to patients. The rule also requires information on medical and drug claim payment policies and practices to be made public, as well as other information as determined appropriate by the secretaries. HHS, DOL, and the Treasury could further build on these reforms by requiring health plans and payers to make public the claims-level drug pricing and discount data (i.e., rebate or spread amounts) they receive from the PBMs. However, the Biden-Harris Administration delayed implementing parts of the rule and has not updated the rule to include the required prescription drug pricing data (HHS, 2023).

Currently, Congress is considering more transparency measures to require PBMs to disclose their pricing and formulary decisions to employers and health plans. These proposals include the Lower Costs, More Transparency Act (2023), the Modernizing and Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (2023), and the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (2023).

PBMs Have No Legal Obligation to Work on Behalf of the Health Plan or Patients

Another reason PBMs engage in anti-patient behavior is that PBMs have no legal responsibility to act in the best fiscal interests of the plan for which they work. Under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), employers that sponsor health insurance for their workers must delegate an individual, committee, or company to be a “fiduciary” to administer the plan (29 U.S. Code §1104, 1974). The law defines a fiduciary as an individual who exercises “discretionary authority or discretionary control” over the health plan (29 U.S. Code § 1002, 1974). The fiduciary must administer the plan “solely in the interest of the participants” and “for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to participants.” In 1998, DOL issued an information letter outlining that fiduciaries must consider both the “quality of services” and the “reasonableness of the fees” that an insurer would charge the employer and its workers for providing health insurance (DOL, 1998). Roughly 139 million individuals receive health insurance through a health plan governed by ERISA (DOL, 2022).

Since employers often lack the expertise or resources to administer a health plan, they will often delegate these tasks to a health insurer acting as a third-party administrator (TPA). The companies then perform plan administration duties such as collecting premiums, adjudicating claims, and contracting with a PBM to manage the employer’s drug benefit.

However, the courts have repeatedly reiterated that TPAs and PBMs do not have a fiduciary responsibility to act exclusively in the interest of the plan. In 2007, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit found that Caremark, the PBM, was not the fiduciary because the PBM did not exercise “discretionary authority” or control over an ERISA-regulated union plan (Chicago v. Caremark, 2007). In a lower court, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey found that plan design and administration were not significant enough to impose a fiduciary duty on the PBM (Mulder v. PCS Health Systems, Inc., 2006).

To change this, policymakers should expand the fiduciary duty under ERISA to include certain services that PBMs provide to employer health plans. Under an extension of fiduciary duty, PBMs would have a legal obligation similar to other entities that contract with employee welfare benefit plans (e.g., retirement plans). For example, under a fiduciary duty, PBMs could have a legal obligation to design drug benefits solely in the interest of the participants.

Lawmakers could amend ERISA to officially designate PBMs as fiduciaries when they design drug benefits for self-funded group health plans. In lieu of a statutory change, DOL could also issue guidance that clarifies that PBMs are fiduciaries, providing evidence that some of the functions they provide exercise discretionary authority over the management of drug benefits of ERISA-regulated health plans.

As policymakers contemplate expanding the fiduciary duty to PBMs, they should ensure that the fiduciary duty PBMs owe to employer health plans is appropriately balanced with PBMs’ financial relationships with drug manufacturers. Policymakers should also consider designing appropriate guardrails against administrative overreach, especially as the Biden-Harris Administration has grossly misinterpreted “fiduciary duty” within the financial services sector.

Extending fiduciary duty to PBMs could further equip companies and employees with powerful legal recourses to ensure that these companies are designing benefits that are in their best interests. In fact, employees have leveraged fiduciary duty to hold employers accountable if they believe their health benefits have been mismanaged. In February 2024, employees at Johnson & Johnson sued the company for allegedly breaching its fiduciary responsibility (Lewandowski v. Johnson and Johnson et al., 2024). According to the lawsuit, Johnson & Johnson paid its PBM to design its drug benefit plan so that workers pay dramatically more for generic drugs under the plan than if they simply purchased the drugs with cash. For example, a 90-day supply of the generic drug teriflunomide could be purchased for as little as $40.55 with cash. But if an employee paid for the drugs with a drug benefit, it would cost the employee and the company a total of $10,239.69.

The ACA Promotes PBM-Health Plan Monopolies

Policymakers should also remove harmful government interventions that financially reward health insurers when PBMs inflate the cost of prescription drugs. A major provision of the ACA, known as the medical loss ratio (MLR), prohibits large health insurers from spending more than 15 cents of every dollar they collect in insurance premiums on profits and administrative expenses (42 U.S.C. 300gg-18, 2010). In the individual market, insurers cannot spend more than 20 cents of every premium dollar on profits and administrative expenses. The remaining 80–85 cents must be spent on health care claims. The architects of the law assumed the MLR would prevent insurers from skimming higher profits from their members and, therefore, encourage insurers to reduce premiums.

As well-intentioned as it might have been, this policy has inadvertently increased the cost of prescription drugs for patients. Because insurers cannot retain more than 15–20 cents in profits and administrative expenses for every 80–85 cents they disperse in claims, insurers can generate higher profits when their PBM manages their drug benefit in a way that increases spending on prescription drugs (CBO, 2022).

For example, a health insurer in the individual market charges members $100 million in premiums, spends $80 million on health care claims, including $20 million in drug claims, and retains the remaining $20 million for administrative expenses and profits in one year. This insurer would have an MLR of 80 percent. To generate greater profits the next year and comply with the MLR rule, the insurer could encourage the PBM with which they contract to raise spending on prescription drugs from $20 million to $40 million, leading to $100 million in total health claims. This would allow the insurer to raise premiums to $125 million. As a result, the insurer could increase the money it directs to profits and administrative expenses by $5 million and remain in compliance with the ACA’s MLR.

No MLR Incentive |

MLR Incentive |

|

Initial Spending on Medical Costs |

$60 million |

$60 million |

Initial Spending on Drug Costs |

$20 million |

$40 million |

Profit and Administration |

$20 million |

$25 million |

Premium Charges |

$100 million |

$125 million |

Medical Loss Ratio |

80% |

80 |

The MLR also incentivized insurers to merge with PBMs (Frank & Milhaupt, 2023). Within Medicare Advantage, where insurers must maintain an 85 percent MLR, evidence shows that after an insurer merges with a PBM, the insurer can use creative accounting for gaming the MLR. For instance, the insurer can direct premium dollars to their own PBM to pay prescription drug claims. The profit that the PBM generates from these transactions does not count against their MLR limits. Therefore, the insurer can spend more on prescription drugs and generate higher profits through a PBM while still complying with MLR’s profit cap.

With these incentives, insurers and PBMs began merging to use the MLR better. Since the ACA took effect, Cigna has purchased Express Scripts (Humer, 2018), CVS Caremark has bought Aetna (Richman, 2018), and United Healthcare has bought Catamaran (Eastwood, 2015) and established OptumRx (Business Wire, 2011). Between 2010 and 2018, the share of Part D beneficiaries enrolled in a plan integrated with a PBM increased from 30 percent to 80 percent (Gray, Alpert, & Sood, 2023). Nationwide, 80 percent of all prescription claims are negotiated by three PBMs integrated with an insurer: Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx (Fein, 2023).

A harmful effect of this trend is that large insurers have started to use their PBMs to raise premiums on patients enrolled in plans with competing insurers. As the largest insurers have merged with the three largest PBMs, smaller stand-alone insurers have had little choice but to contract with PBMs that are integrated with their competitors. A 2023 study in the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the premiums for Part D plans that contracted with a competitor’s PBM were 65 percent higher than the premiums of insurers that were integrated with a PBM in 2018 (Gray, Alpert, & Sood, 2023). This suggests that the largest PBM-insurer conglomerates are designing formularies for their competitors to raise their premiums and disadvantage them in the marketplace.

The ACA Promotes PBM-Pharmacy Monopolies

The ACA’s MLR requirements have also driven the consolidation of PBMs and pharmacies. As the largest PBMs merged with insurers, they acquired or established their own pharmacies and inserted language in contracts to steer members to their pharmacies rather than to independent ones. Between 2015 and 2021, the share of Part D prescriptions that were dispensed by a pharmacy owned by their PBM-integrated insurance plan increased from one-quarter to one-third, according to a 2023 report from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) (MedPAC, 2023). Nationwide, pharmacies operated by the three largest PBMs, Caremark, OptumRx, and Express Scripts, generated 57 percent of all specialty pharmacy revenue in 2018 (Fein, 2019).

The MLR contributed to PBM-integrated insurers consolidating the pharmacy industry and raising consumer costs. A 2024 report by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) details how the MLR encourages PBMs to pay higher reimbursements to their in-house pharmacies: “For example, if an affiliated insurer pays an inflated price for a specialty generic to its affiliated pharmacy, the higher payment is credited as spending on clinical care and helps the affiliated insurer satisfy its MLR obligations” (FTC, 2024).

Because of these incentives, evidence is sufficient to show that patients and taxpayers spend more on prescription drugs when patients fill their prescriptions at pharmacies owned by the PBM that manages their drug benefits. A case study by the FTC found that the three largest PBM-integrated insurers paid pharmacies they own more than they paid unaffiliated pharmacies for two generic drugs. In the commercial market, PBM-integrated insurers paid affiliated pharmacies 80–90 percent more than they paid unaffiliated pharmacies. In Part D, PBM-integrated insurers paid affiliated pharmacies more than 30 percent more than they paid unaffiliated pharmacies. In other words, PBMs are vertically integrating to raise prices for patients and taxpayers alike.

Policy Recommendations

Policymakers should enact reforms that directly address the perverse incentives in the PBM industry to lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs for patients. America First policies would give PBMs the flexibility to design benefits for the unique needs of patients and employers while ensuring that PBMs also work in the best interests of the health plan, the patient, and the taxpayer.

Require Transparency from PBMs: Lawmakers should require PBMs to provide a report to employers and Part D plans that details their rebate and claims data, their formulary decisions, the net cost of the drugs on their formularies, affiliate pharmacies, and other relevant information needed for health plans to make cost decisions. Policymakers should also enforce provisions of the CAA and the ACA that require greater transparency between the health plan and the PBMs.

End Perverse Incentives that Favor PBM-Insurer Monopolies: Lawmakers should reform the MLR to prevent this policy from increasing the cost of care for families. Policymakers should also explore regulatory reforms to prevent health insurers from gaming the MLR by consolidating with PBMs and health care providers. In 2023, Senators Mike Braun (R-IN) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) issued a letter to HHS, urging the agency to determine if PBM insurers were charging higher prices at their in-house pharmacies because of the MLR (Warren & Braun, 2023).

Expanding Fiduciary Duty: Lawmakers could amend ERISA to officially designate PBMs as fiduciaries when they design drug benefits for self-funded group health plans. DOL could also issue guidance that clarifies that PBMs are fiduciaries, providing evidence that some of the functions they provide exercise discretionary authority over the management of drug benefits of ERISA-regulated health plans. In 2023, Senators Mike Braun and Roger Marshall (R-KS) offered and withdrew an amendment to the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act that would have enacted this reform (Proposed Amendment, 2023). Braun and Marshall successfully offered an amendment requiring the DOL to study the impact of imposing fiduciary responsibility on PBMs (Braun & Marshall, 2023).

Ban Spread Pricing in Government Programs: Policymakers should prohibit spread pricing in contracts between a PBM and public health programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid. The Modernizing and Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (2023) and the Lower Costs, More Transparency Act (2023) would enact a spread pricing ban in Medicaid.

Strengthen Antitrust Enforcement: Policymakers should direct the FTC to investigate and penalize PBM practices that raise prescription drug spending and curtail competition. In 2021, the FTC issued a report that indicated many common rebate arrangements that drug manufacturers and PBMs establish in commercial and Part D plans potentially violate the Sherman Act (FTC, 2021). In addition, the FTC found that the PBMs’ vertically integrated and concentrated market structure has allowed them to profit at the expense of patients and independent pharmacists (FTC, 2024).

Conclusion

PBMs have enormous potential to negotiate lower prices because of the substantial number of patients they represent, but they operate in a system with perverse incentives. The current system has encouraged PBMs to favor high-cost brand-name drugs over more affordable options, including generic drugs. It has inadvertently raised list prices, which has hurt patients, who must pay more for their drugs. Furthermore, the ACA has incentivized insurers to merge with PBMs and pharmacies, which has encouraged these companies to benefit from higher spending on prescription drugs.

Policymakers should remove these perverse incentives in the PBM industry to ensure that PBMs negotiate lower prices for families. In addition, lawmakers should require PBMs to manage drug benefits in the best interest of the employers for whom they work. Furthermore, PBMs should provide employers with more transparency in how they design their drug formularies and detailed claim information that employers need to make decisions for their employees. High drug costs are a top concern for Americans, and solutions that address the misaligned incentives of PBMs could make meaningful progress toward putting patients back in charge of their health care.

[1] Net revenue is the amount of money a drug manufacturer makes after subtracting rebates and other discounts they give to PBMs and health plans.

References