Optimizing Investment Guardrails The Challenge of Protecting U.S. Companies, Data, and Infrastructure from the CCP

Key Takeaways

Foreign direct investment in American private enterprise represents a lucrative source of capital for individual businesses. While it is a vital factor in ensuring the success of critical sectors of the U.S. economy, it also presents important national security risks.

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) was founded in 1975 to address these vulnerabilities. The CFIUS is an interagency committee housed at the Department of the Treasury that screens and assesses the national security implications of foreign ownership of U.S. corporations. However, it is not equipped to contend with the manifold threats to the United States resulting from the malign conduct of a great power adversary like the People’s Republic of China.

CFIUS must be granted the ability to create a “countries of concern” list that includes China. Designated foreign companies must be required to maintain their data entirely in the United States. Foreign investors seeking to purchase commercial investments in the United States should not be entitled to comprehensive due process, and CFIUS must be retooled to protect our sensitive infrastructure sites and military installations.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is a comprehensive threat to our national security and is embedded into nearly every aspect of American life, from our reliance on cheap manufactured goods to our vulnerable defense microchip supply chains to our compromised personal data on TikTok. China’s exploitation of key features of the U.S. business and civil sectors is an integral part of its plan to use U.S. vulnerabilities to its own economic and strategic advantage.

Conventional commercial risks, including trade secret theft and unfair competition, and massive volumes of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) present important national security risks. The offshoring of manufacturing, foreign ownership of utilities, and non-American ownership of other critical domestic industries go beyond economic considerations and directly affect the United States’s ability to defend itself effectively. Substantial foreign investment into America’s technology sector requires additional scrutiny to ensure that American consumers and their data are protected.

CCP acquisitions of property, including agricultural and ranch land, as well as land adjacent to military installations and critical infrastructure, have exposed our homeland to the potential of Chinese surveillance and sabotage. Critical infrastructure is any asset that, if incapacitated, would have a debilitating impact on national security, economic security, or public health, including gas and oil pipelines, electrical power grids, military installations, telecommunications facilities, and public transportation systems.

Despite these inherent vulnerabilities, overseas capital flows boost investment activity and connect the United States to the opportunities enabled by integration into global trade and commerce. FDI in American private enterprise represents a lucrative source of capital for individual businesses and is a vital factor in ensuring the success of critical sectors of the U.S. economy. The United States is the largest recipient of foreign direct investment in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), with second-quarter 2023 investment totaling 80.6 billion USD—just under 35 percent of the world’s inbound FDI that quarter (OECD, 2024).

To address FDI-related liabilities while seeking to maintain enough openness to promote healthy investment, the Ford Administration created the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) in 1975. CFIUS is an interagency committee housed at the Department of the Treasury that screens and assesses the national security implications of foreign ownership of corporations in the U.S. (Exec. Order No. 11858, 1975).

In some cases, foreign ownership comes from nations of minimal concern. Fellow Five Eyes member nations—Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom—are all listed as “excepted foreign states.” For example, Canada Pacific Railway’s acquisition of U.S. company Kansas City Southern, which formed a continent-spanning railway network (Canadian Pacific Kansas City, 2022), was an exempt transaction.

In other instances, transactions may originate in allied, but not excepted, foreign states. For example, the pending purchase of U.S. Steel by Japanese corporation Nippon Steel would leave the United States with considerably less American-owned steel foundry capacity. Opponents of the deal also argue that while Japan has been a trusted economic partner and a treaty ally since the end of World War II, Nippon Steel’s ownership of assets in both the U.S. and China raises concerns of conflict of interest (Egan, 2024). Proponents of the deal argue that Japan is among America’s most trusted allies and in the event of a war with China, Russia, or North Korea, would certainly be on our side and inclined to maximize steel production to aid the war effort.

By the summer of 2024, the incumbent president and both major party candidates for the November presidential election had come out publicly against the acquisition. In September 2024, President Biden reportedly signaled that he would kill the deal, and CFIUS reportedly delivered an official letter to Nippon Steel ostensibly listing irreconcilable national security concerns (Tita, 2024).

People’s Republic of China (PRC) investments in the U.S., however, pose a unique threat. China has enacted authoritarian economic practices (Department of Homeland Security, 2020)—from military-civil fusion initiatives compelling civilian cooperation with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (Farrow, 2023) to their National Intelligence Law of 2017, which compels the handover of personal data without a warrant. China has abused its power in international commerce to consistently violate international norms on intellectual property (Siddiqui, 2023), copyright (Na, 2023), and other commercial protections (Sutter, 2021). Chinese researchers across the Western world have been charged with theft of secrets from universities as part of CCP-backed schemes, and American companies operating in China are permitted no expectation of due process or property rights (O’Keeffe, 2023).

CFIUS is not equipped to contend with the manifold threats to the United States resulting from the malign conduct of a great power adversary like the PRC. CFIUS was meant as a screening mechanism for foreign corporations from various nations, including allies, whose acquisition of American companies may affect our national security, even if inadvertently. We have not dealt with a malign great power like China with the ability and motivation to invest substantially in critical sectors of the U.S. economy.

To deal with these shortcomings, CFIUS must first be granted the ability to determine which countries pose the greatest threat. They should adopt a “countries of concern” list informed by those used by the Departments of Commerce and Defense. This list should include China and nations that might be identified as serving as fronts, and companies from listed nations should be required to undergo enhanced screening and have stricter controls on investment.

Second, data and onshoring requirements should be aggressively enforced through mitigation measures. Companies that traffic in significant amounts of consumer data, whether commercial, personal, or genetic, should be required to maintain that data entirely in the United States. Access from overseas should be forbidden and aggressively policed, with severe financial and legal penalties for violations.

Third, foreign investors seeking to purchase commercial investments in the United States should not be entitled to comprehensive due process. CFIUS is a creation of the executive branch, and the president is, by statute, exempted from judicial review when the decision is made directly by him. That same exemption should be extended to all CFIUS reviews, and due process in American commerce should be afforded only to American companies and citizens.

Finally, the Committee must be retooled to protect our sensitive infrastructure sites and military installations. Legislation should require screening of all land purchases of foreign adversarial nations and mandate filings for land purchases near sensitive sites. The list of sensitive sites must be more comprehensive. In addition, the classification of sites already on the list (e.g., missile bases, training facilities, flight paths, etc.) and designated proximities must be simplified.

History of the Committee

When it was founded in 1975, CFIUS’s principal responsibility was simply to monitor and collect data related to transactions involving foreign purchasers. That purview quickly expanded to include governance and oversight.

In the 1980s, executive orders by Presidents Carter and Reagan amended the underlying text. President Carter’s executive order was a minor housekeeping adjustment concerning trade positions (Exec. Order 12188, 1980), while President Reagan substantively adjusted President Ford’s original order by creating the investigative process and the presidential reporting process and by empowering the Committee with Section 721 of the 1950 Defense Production Act (Exec. Order 12661, 1988). This power to review foreign purchases of American businesses, originally granted to the president through the Exon-Florio amendment to the Defense Production Act in 1988, was then delegated to CFIUS by executive order (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2005).

Submissions and disclosures to the Committee remained voluntary, but any transactions not reported to CFIUS were subject to direct intervention, such as a forced review or divestment order at any time (Jackson, 2020). This looming threat of potential action by the executive branch served as an informal requirement with which most purchasers ultimately complied, causing submissions to become a de facto requirement over time.

Congress expanded CFIUS’ authority further in 1992 via the Byrd Amendment, which itself was a revision of the Exon-Florio Amendment. Changes included requiring reviews whenever the purchaser could be acting on behalf of a foreign government, directly or indirectly, and when the transaction could impact national security (Jackson, 2020). This two-part test led to disputes between Congress and CFIUS, most notably during the DP World ports controversy when Congress held hearings and called for action, while CFIUS determined that the purchases were not sufficiently disruptive to warrant action (King & Hitt, 2006). DP World, a Dubai government-controlled port management company, purchased several U.S. ports through mergers and acquisitions from 2006 to 2007. Ultimately, Congress ordered them to divest to an American holding company.

CFIUS was codified in legislation by the Foreign Investment and National Security Act (FINSA) of 2007. FINSA was largely crafted to resolve problems exposed by the DP World ports controversy. These changes included:

- Codifying CFIUS, giving it statutory authority as a congressionally empowered entity, and consequently, granting it more oversight power and expectations for closed-door congressional briefings;

- Solidifying CFIUS membership (see list below) while also expanding it to include the “Director of National Intelligence (DNI) and Secretary of Labor as ex officio members with the DNI providing intelligence analysis” (Jackson, 2020) and granting authority to the president to add members to the committee on a transaction-by-transaction basis;

- Empowering the president (and, therefore, CFIUS) by increasing the number of factors that can be considered in transaction decisions, such as effects on infrastructure, energy production, and cases where foreign governments were direct parties.

These changes were further modified by President George W. Bush’s complementary executive order, which was largely concerned with implementing FINSA. It included additions to membership of the Committee, now including the United States Trade Representative and the director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy, as well as designating several presidential assistants and White House officers as presidential representatives (Exec. Order 13456, 2008). The Secretary of Homeland Security was added as a member in 2003, under an earlier Bush order, after it was established by legislation (Exec. Order 13286, 2003).

The statutory text exempts CFIUS from most conventional legal scrutiny. Specifically, 55 U.S.C. § 4565(e)(1), written into law by FINSA in 2007, states that the president’s findings “shall not be subject to judicial review,” but this principle has been challenged and undermined.

Post-FINSA reforms were tested in the controversial 2012 case of the Ralls Corporation, an entity affiliated with Chinese machinery and construction firm Sany Group, which purchased four plots of land slated for wind farm development in Oregon. These wind farms, however, were in proximity to a nearby bombing range operated by the United States Navy. Ralls Corporation initially did not seek any CFIUS processes and avoided filing altogether but was stopped by a presidential order (“Regarding the Acquisition…”) on September 18, 2012, ordering them to cease construction and development (Fitzpatrick, 2016). Ralls’ Chinese ownership, combined with the land’s proximity to the military installation, raised fears about potential surveillance of U.S. weapons technology at the range.

In the 2014 lawsuit Ralls Corp. vs. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled largely in Ralls’ favor. The decision hampered CFIUS’ authority in several areas, including the still technically voluntary filing process, which was a point of contention in the case (Fitzpatrick, 2016). Lower courts had favored CFIUS and cited Ralls’ failure to initially file as waiving most of their due process rights. The decision also expanded due process concerning almost all of CFIUS’ provisions. The Obama Administration was then compelled to give more than 3,000 pages of information to Ralls Corporation’s lawyers, much of which was unclassified—but deliberately non-public—concerning CFIUS’ processes and review of the transaction.

Further disputes continued between CFIUS and Ralls before Ralls eventually sold the wind farm to a “Dr. Xiuexin Tang” without further incident (Welitzkin, 2015), although CFIUS had reportedly objected to Tang’s purchase of the property.

The increasing interconnectedness of the Chinese and American economies during the 2000s and 2010s, combined with the failures inherent in the CFIUS process that became apparent from the Ralls ruling, brought CFIUS modernization concerns to prominence during the Trump Administration. This culminated in the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), a holistic revamp of the CFIUS process and jurisdiction.

Some of FIRRMA’s additions or changes to CFIUS authority and purview included:

- Granting review power over transactions that involved the transfer or acquisition of real estate within a certain proximity to government facilities or military installations or the acquisition of “critical infrastructure or critical technologies” (Jackson, 2020);

- Permission for CFIUS to discriminate based on country of origin for investor/transaction applicants;

- Creation of a two-track system: a shorter, less in-depth “declaration” for non-hostile countries or minor transactions and a longer, more comprehensive “notice” for adversarial countries, major transactions, or transactions that may include critical technologies;

- Mandating filings with CFIUS in some, but not all, cases.

FIRRMA was the last major reform that modified CFIUS’ authority or decision-making process as of the writing of this report.

Recent Case Studies

Perhaps the most high-profile CFIUS case has been the struggle to manage risks posed by the wildly popular short-form video app TikTok and its CCP-owned parent company ByteDance. Officially headquartered in the Cayman Islands, although physically headquartered in the PRC, TikTok’s meteoric rise came alongside questions about its foreign ownership and data practices. Acting on congressional concerns, CFIUS began an investigation into TikTok in mid-2020. The Committee made a negative recommendation to President Trump, who proceeded with various executive actions to force the divestment or banning of TikTok.

All of these, however, were rolled back or dropped by President Biden. In exchange, President Biden stated his intent to extract compromises from TikTok, such as through “Project Texas,” an arrangement for storing American user data on American soil, explained in detail later in this report (Culpan, 2023). The Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act of 2024 ordered TikTok to divest from the CCP or face a prohibition on app store availability and web hosting services in the United States. However, CFIUS still could be used to take conclusive action if the Biden Administration chose to pursue it.

Other disputes over data protection received increased scrutiny under the Trump Administration as well. The administration pressed a Chinese holding company to divest from dating app Grindr after similar data concerns. Early in 2020, the Trump Administration and CFIUS approached Grindr’s holding company with presented an ultimatum of either divesting the app or having U.S. access restricted (Whittaker, 2020). The PRC-based holding company was accused of selling user data, including HIV status, to external third companies that included advertisers and data trawlers under dubious circumstances (Coldewey, 2018). The app was eventually sold under continued pressure from the Trump Administration.

Similar data concerns presented themselves with the company StayNTouch, an American software company that was in the process of being purchased by a Chinese investment firm. The company’s software was largely used in the hospitality industry and had access to much personal information related to travel and payment processing (Swanson, 2020). President Trump ordered divestment in that case as well, citing broader national security concerns. The software was in use at the time with large hospitality chains such as MGM.

The Trump Administration also took measures to protect economic competitiveness and security against Chinese domination of certain industries. CFIUS may take into account whether an entirely domestic merger or acquisition may result in decreased competitiveness, leading to foreign advantage in sensitive sectors. In the case of a proposed Qualcomm-Broadcom merger, President Trump blocked the deal on grounds of economic security. Broadcom would attempt to purchase Qualcomm, but fears emerged that Broadcom would cut research and development, particularly of 5G technology, paving the way for potential Chinese dominance of the sector (Leiter et al., 2018). President Trump blocked the acquisition on those grounds.

CFIUS came to public attention most recently in May 2024 when President Biden barred a “Chinese-backed cryptocurrency mining firm” from owning and using land near Francis E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming (Hussein and Miller 2024). While this was a proper use of CFIUS, Chinese ownership of the land had escaped scrutiny since 2022. The violation was discovered only after CFIUS received a tip from a member of the public. It is notable that this outcome was only made possible by the review powers granted by FIRRMA, which included CFIUS’ jurisdiction over the ownership of land in proximity to military sites.

Additional threats regarding CCP access to land near sensitive sites have come to light in recent years. In 2022, Chinese food manufacturer FuFeng Group purchased land near Grand Forks Air Base, North Dakota. Locals immediately protested the move, raising concerns about its proximity to the base and the reasons for FuFeng selecting that property. CFIUS refused to act, claiming it had no jurisdiction over that purchase due to it not meeting proximity requirements. The project eventually fell through largely due to local pressure (Razdan, 2023).

In 2019, Chinese billionaire and energy investor Sun Guangxin purchased thousands of acres in Southwest Texas, seeking to build a wind farm in Val Verde County. CFIUS initially approved the purchase in December 2020, but residents and state politicians raised concerns about the purchase’s proximity to Laughlin Air Force Base and its training routes for pilots. Eventually, the project was stalled by mounting state-level pressure that culminated in the Lone Star Infrastructure Protection Act (LSIPA). The law restricts the wind farm’s ability to connect to Texas’ power grid (Coronado, 2023), though a legal battle is ongoing (Hyatt, 2024).

The case of ICON Aircraft, beginning in 2022, illustrates the vulnerabilities enabled by CFIUS’ inability to flag adversarial nations and prevent their access to dual-use technologies. ICON Aircraft specialized in light sport aircraft and ultralight materials for flight. A Chinese technology investment firm, Pudong Science and Technology Investment (PDSTI), became its plurality investor. The board members of ICON, which included former Boeing and General Atomics members, were slowly replaced by board members favored by PDSTI. The company faced financial difficulties, and concurrently with the change in board composition, PDSTI began exporting ICON’s tech and planes to China (O’Keeffe, 2022).

ICON’s founders urged CFIUS to intervene. Although ICON’s own counsel assured reporters from the Wall Street Journal that the craft had no military potential, the founders urged CFIUS to intervene on the basis that the aircraft was being explored for such development by the Department of Defense. Despite the complaints made by ICON’s founders to CFIUS, alongside a lawsuit in Delaware concerning the transfer of intellectual property, CFIUS took no action. The company eventually filed for bankruptcy in April 2024, after transferring planes and design documentation to China, and floated further licensing of its IP to stay afloat (Randles, 2024).

The above cases illustrate flaws rooted both in government officials’ decisions and CFIUS’s structures. Ultimately, the success or failure of CFIUS in its mission depends on the attitude of the managing staff at the Department of the Treasury and the president’s personal determinations, but the statutes and regulations guiding CFIUS’ internal operations provide the crucial groundwork on which these decision-makers rely.

Modern Operations of the Committee

CFIUS’ current membership includes representatives from the executive branch. Members include or represent the following offices and departments:

- Secretary of the Treasury, Chair

- Secretary of State

- Secretary of Defense

- Secretary of Homeland Security

- Secretary of Commerce

- Secretary of Energy

- Attorney General

- United States Trade Representative

- Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy

- Secretary of Labor*

- Director of National Intelligence*

- Director of the Office of Management and Budget**

- Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers**

- Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs**

- Assistant to the President for Economic Policy**

- Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism**

* indicates a non-voting but ex officio member. ** indicates a White House representative who is also non-voting.

The Secretary of Labor and Director of National Intelligence are ex officio and non-voting, observing members. The Director of the Office of Management and Budget, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, and certain assistants to the president serve to represent certain White House committees—the National Security Council, National Economic Council, and Homeland Security Council—although their representatives are non-voting members as well.

The framework for decisions on purchase reviews and investigations is determined on a case-by-case basis, guided by the Committee’s actions. The primary investigating agency is determined by which industry or sector is affected by the purchase or acquisition, and the Secretary of the Treasury may appoint assisting agencies as well. Once the purchase is formally submitted to CFIUS, an oversight department is determined, which may occur over about 30 days. The overseeing department or agency then begins an investigative process with the help of CFIUS staffers and researchers to determine if the purchase or acquisition violates any of several thresholds or criteria that CFIUS either maintains on its own or is required by law to evaluate.

Some of these criteria include the following congressional findings, which were included as part of FIRRMA’s text:

[W]hether a covered transaction involves a country of special concern that has a demonstrated or declared strategic goal of acquiring a type of critical technology or critical infrastructure that would affect United States leadership in areas related to national security; the potential national security-related effects of the cumulative control of, or pattern of recent transactions involving, any one type of critical infrastructure, energy asset, critical material, or critical technology by a foreign government or foreign person; […] the control of United States industries and commercial activity by foreign persons as it affects the capability and capacity of the United States to meet the requirements of national security; […] whether a covered transaction is likely to have the effect of exacerbating or creating new cybersecurity vulnerabilities in the United States or is likely to result in a foreign government gaining a significant new capability to engage in malicious cyber-enabled activities against the United States[.] (Public Law 115-232, 2018)

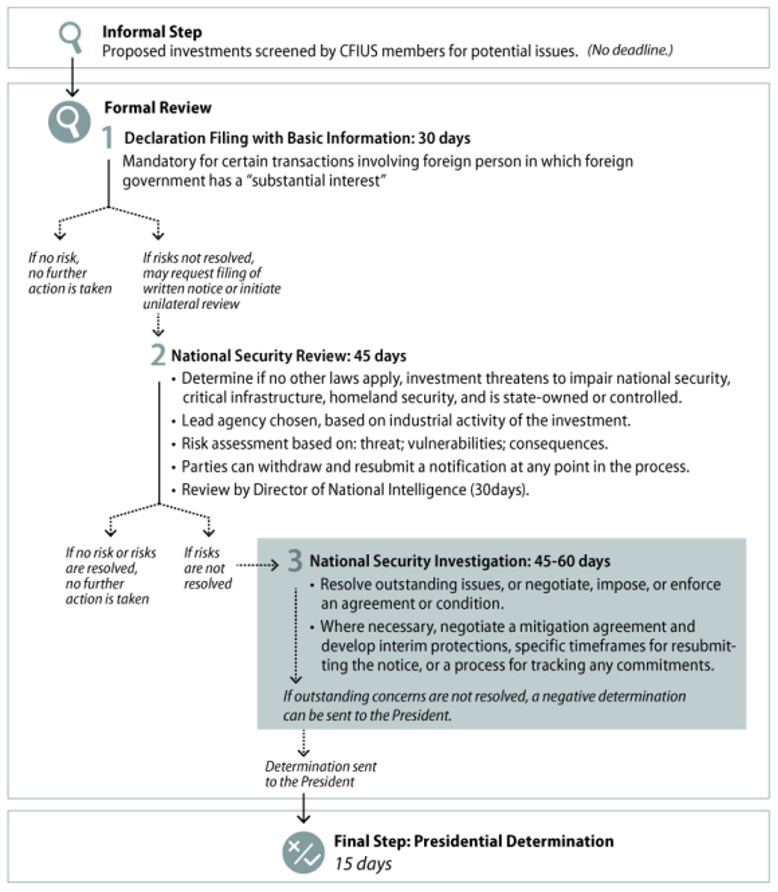

FIRRMA’s revisions to CFIUS brought a variety of ways for deals submitted to the Committee to be resolved. Figure 1 below illustrates these potential paths.

Upon filing any declaration (short-form) purchase with CFIUS, the Committee is required to respond to the purchaser within 30 days. Typically, declarations are used when the exposure of foreign ownership is minimal or when the “substantial interest” originated from a country with friendly relations with the United States. The aforementioned “excepted foreign states” receive minimal or no scrutiny.

The unstated purpose of most CFIUS declarations is to pre-empt further action from CFIUS. When CFIUS grants explicit clearance during the declaration process, it promises not to initiate further investigative proceedings unless something substantively changes in the purchase. CFIUS explains this process as granting a “safe harbor letter.” Alternatively, CFIUS may advance transactions by declining to act, but this does not shield the parties involved from further investigation.

While declarations are voluntary for most commercial transactions, FIRRMA establishes some mandatory filings, particularly those that may involve foreign entities’ ownership of critical technologies. Companies involved in critical technologies, critical infrastructure, or the storage of U.S. citizens’ data are considered TID (technologies-infrastructure-data) businesses, a critical determination relevant to multiple parts of the CFIUS decision-making process.

The filing of notice (long-form) purchases with CFIUS differs from the filing of declaration (short-form) purchases in several ways. First, the process for notice purchases is rigidly guided by time restrictions: If CFIUS is unable to resolve or complete a transaction review within 45 days, the process is escalated to an investigatory period of 45 additional days; if this process fails to complete, or if the determination is unsatisfactory, CFIUS delegates the decision to the president.

Second, the notice process is much more rigorous than the declaration process. For declarations, CFIUS sets forth a guideline that the filing must not exceed five pages and must include basic information on the transaction, including proposed purchasers, investors, and the business activity of the company to be purchased. For notices, filing is as comprehensive as possible. CFIUS looks upon the intentional omission of data unfavorably. Notices also incur filing fees based on the value of the underlying businesses. CFIUS can only work with documents that companies volunteer, asCFIUSdoes not have subpoena power.

Third, in contrast to declarations, which either result in clearance, no action, or referral for notices, notices are definitive and final. The only outcomes that CFIUS can return to a notice filing are acceptance, acceptance with mitigation, or denial. The escalation of issuing authorities for these acceptances and denials can range from CFIUS itself to the president, but the determinations irrevocable except in case of substantive changes regarding the transaction. Presidential determinations, however, are required to be made public in the Federal Register.

Mitigation measures, as determined by CFIUS, are the conditional monitoring or requirements to which involved parties or companies may be subject. Examples of mitigation measures taken by businesses, as listed in the 2022 annual report, included but were not limited to:

[P]rohibiting or limiting the transfer or sharing of certain intellectual property, trade secrets, or technical information; ensuring that only authorized persons have access to certain technology, systems, facilities, or sensitive information; restricting recruitment and hiring of certain personnel; establishing a corporate security committee, voting trust, and other mechanisms to limit foreign influence and ensure compliance, including the appointment of a U.S. Government-approved security officer and/or member of the board of directors and requirements for security policies, annual reports, and independent audits[.] (CFIUS, 2023)

Recent examples of mitigation measures include those offered to TikTok by the Biden Administration after they canceled the divestment order by President Trump. The measures, which came to be known as Project Texas, are a joint effort between Oracle Corporation and U.S.-based TikTok Data Security Inc., a freshly created subsidiary of TikTok. Project Texas stipulates that Oracle will store the data on their U.S.-based servers while acting as a gatekeeper. TikTok Data Security will monitor the data on an operations level, with CFIUS requiring that all employees either hold green cards or be U.S. citizens. The board of TikTok Data Security is also directly accountable to CFIUS (Culpan, 2023).

TikTok’s agreement with CFIUS, however, was allegedly violated on several occasions, as reported by numerous outlets. ByteDance allegedly allowed access to U.S. users’ data from abroad (Baker-White, 2022), used the app to track U.S. journalists (Murphy, 2022), and stored users’ financial information on Chinese servers (Levine, 2023). Despite numerous documented violations regarding data storage, the Biden Administration did not punish ByteDance via CFIUS.

Compliance with mitigation measures is verified in several ways, including voluntary self-reporting, on-site inspections, third-party audits, or full investigations. Violation of mitigation terms may result in penalties to the relevant company or a re-initiation of the CFIUS review, which may result in re-determinations that force divestment or similar measures.

It is important to note that CFIUS proceedings are not generally open or accountable to the public. There is no public acknowledgment of progress through the program to anyone but the involved parties, except in the case of a presidential determination. Companies may voluntarily disclose information to the public, although there is often no incentive to do so. When presidential decisions are required or when litigation occurs between CFIUS and the parties involved, details of the case are likely to leak, at least in part, through court proceedings. This was the case with Ralls v. CFIUS.

The oversight of interstate commerce is constitutionally assigned to the legislative branch but is ultimately executed by the president. Therefore, presidential agency and fortitude generally govern the use of CFIUS. The Obama Administration’s case against the Ralls Corporation was lost but was pursued to completion in the interests of national security. This tenacity arguably led to the writing of FIRRMA as a tool to resolve problems that came to light because of that case.

The Biden Administration’s reversal of the Trump Administration’s determinations concerning TikTok has undermined CFIUS and U.S. national security. President Biden proposed unique carve-outs for TikTok in the form of Project Texas, even though initially, CFIUS largely concluded that cooperation with ByteDance was untenable in its review under President Trump in 2020. China, as a known hostile actor and constant violator of U.S. norms, requires the strictest mitigation measures.

Analysis of the 2022 CFIUS Annual Report

CFIUS has been fortified by reforms resulting from its controversies and failures. FINSA was drafted in response to the DP World Ports scandal, which would have passed CFIUS’ review at the time. FIRRMA was drafted due to persistent concerns that problem countries like China faced insufficient scrutiny.

Despite FIRRMA, FINSA, and several other powers—emergency and otherwise—that the president and Committee can use, CFIUS remains unable or unwilling to examine all eligible transactions. The annual CFIUS report to Congress reveals gaps in oversight and enforcement, even after recent reforms.

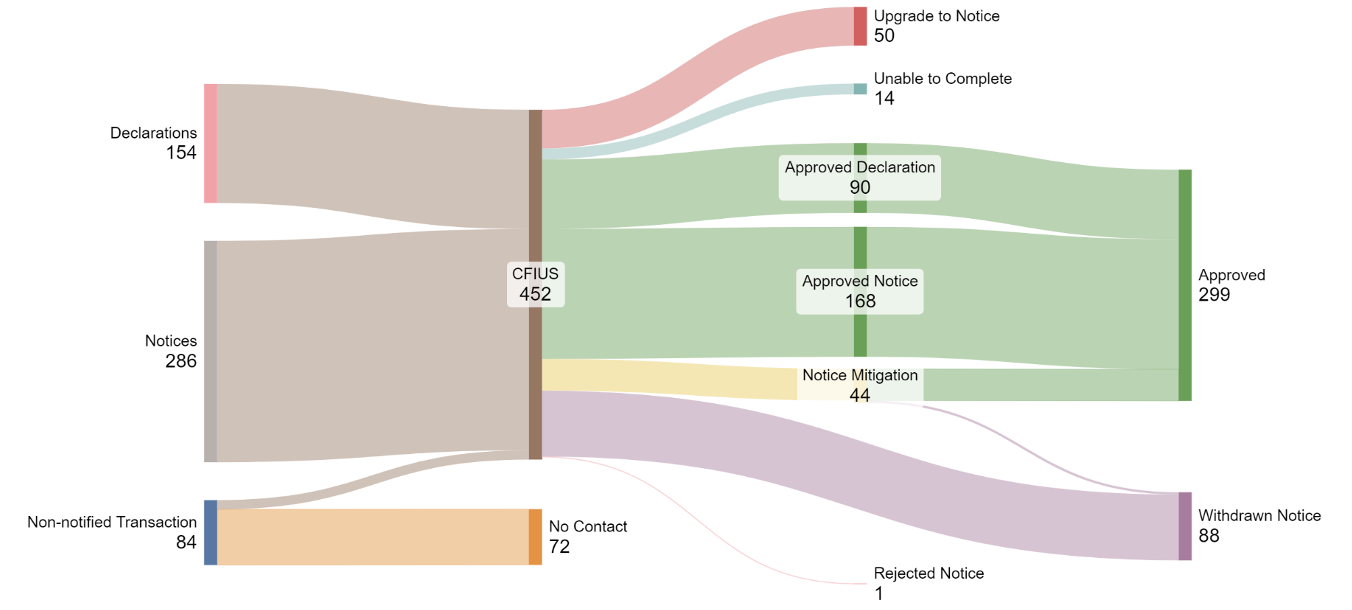

The calendar year 2022 report was the most recent available during the writing of this paper. With the full implementation of the majority of FIRRMA, the shortened “declaration” path for transaction submission received 154 entries, down slightly from 164 in 2021 but still up significantly from 126 in 2020. Of these, 90 received approval, and 50 received a recommendation to perform a full filing. CFIUS advised 14 that they were unable to complete the transaction for various reasons.

There were 286 “notices,” or full information transactions, filed with CFIUS in 2022, up from 272 the previous year and up from 187 in 2020. Of these, 162 received investigations, of which 41 required “mitigation”—national security measures—to control potential exposure to risk on behalf of the U.S. government. After CFIUS returned with requirements for mitigation, three of those 41 filings were withdrawn. Overall, 88 of the 286 notices were withdrawn, and 68 were refiled either in 2022 or 2023. Of the 88 withdrawals, 12 withdrew after CFIUS informed applicants they were unable to identify possible mitigation measures to resolve national security concerns or after they refused proposed mitigation terms. Eight of those 12 withdrew their notices for “commercial reasons.”

However, a large number of deals (84) are hidden in what CFIUS calls “non-notified transactions.” This means that the companies did not notify CFIUS themselves and that CFIUS became aware of the transactions by other means.

Figure 2 below reflects the actions taken by CFIUS in response to individual filers and non-notified transactions.

On a larger scale, the “non-notified transactions” reported by CFIUS constitute about 16 percent of eligible transactions under their authority. They pursued only 12 of the 84 non-notified transactions. While a decision to pursue a transaction is up to the Committee’s discretion, the lack of information on such transactions is concerning. There is no breakdown of non-compliant purchasing companies nor of the sectors to which they belonged.

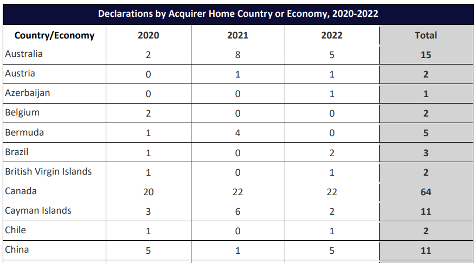

In addition, countries that have been declared or designated as adversarial nations by multiple parts of the federal government continue to use the short-form declaration filing system. For example, the People’s Republic of China submitted five of the 154 short “declaration” filings in 2022.

China is granted the same privileges as any other country to submit short-form declarations. Peter Harrell, former National Security Council and National Economic Council member under President Biden, testified to the United States-China Economic Security Review Commission that CFIUS performs all transactions on a “case-by-case” basis and maintains no “prohibitions on Chinese investment” (United States-China Economic Security Review Commission, 2024, 3:24:40-3:26:00).

Concerningly, there is no guarantee that CFIUS data reflects the applicant’s accurate country of origin, only their stated country of affiliation. The documents submitted to CFIUS are the only documents that CFIUS can access, as the Committee lacks subpoena power and must lean entirely on Office of the Director of National Intelligence for non-volunteered information. Therefore, intentional obfuscation may result in Chinese companies registering under another country’s flag.

China’s international commerce strategy involves deepening ties with third countries that the United States views more favorably than China, allowing Chinese companies to evade sanctions and penalties. Recent state visits by President Xi Jinping to Vietnam underscore this strategy (Anstey, 2023).

E-commerce giant Shein has moved its corporate address to Singapore, and founders and executives of other Chinese companies, such as TikTok and Alibaba, have also made their way to the city-state (Vasagar, 2023), introducing large amounts of Chinese capital. Singapore (Reuhl and Lewis, 2022) has also seen a significant amount of offshoring from China to avoid potential future consequences of a U.S.-China trade war.

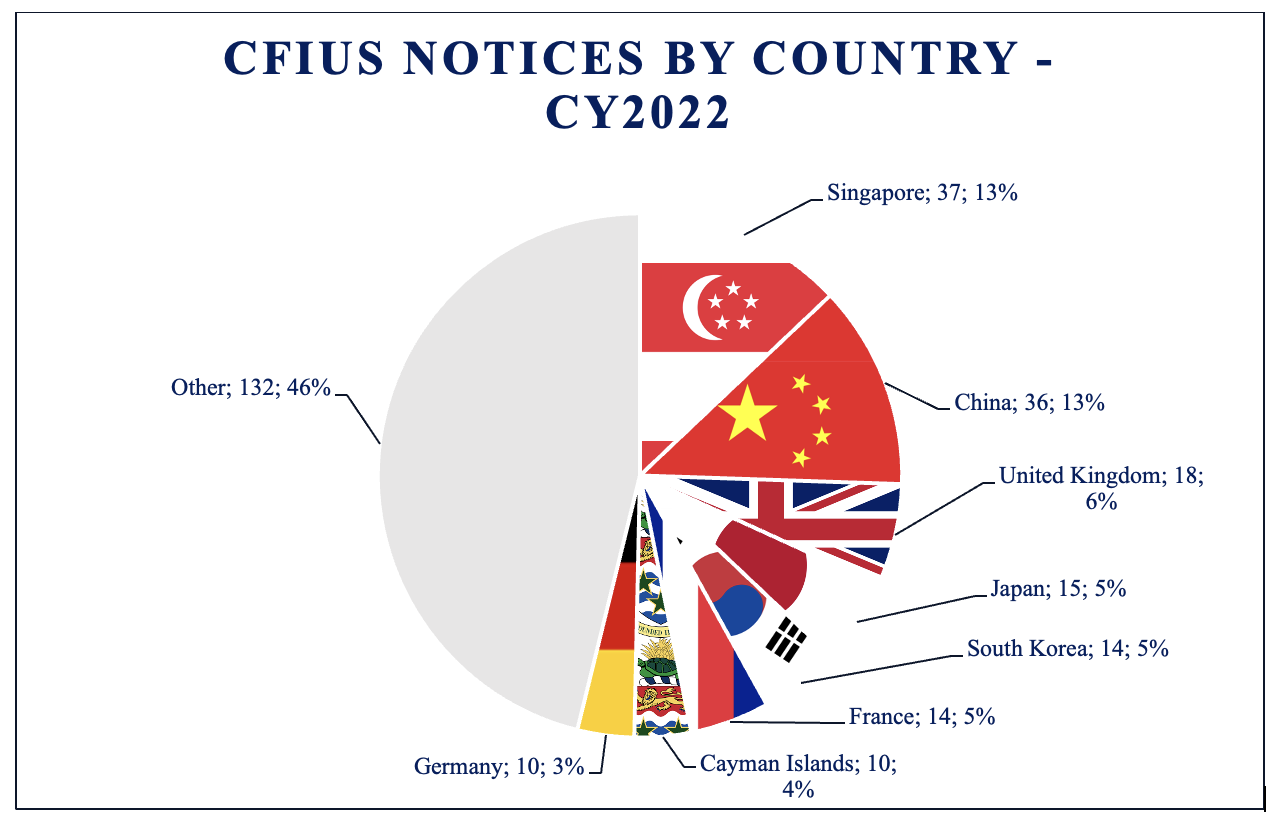

It should raise concern that Singapore, which barely has the equivalent GDP of the state of Missouri, is purchasing more U.S. companies through notices than France or Germany is purchasing through declarations and notices combined.

The Cayman Islands is also a commonly used address for Chinese companies to incorporate abroad (Coy, 2023). For example, ByteDance, the owner of TikTok, is incorporated in the Cayman Islands.

As illustrated in Figure 4 below, of all notices filed in 2022, 83 of 286 were filed by China, the Cayman Islands, and Singapore combined.

The higher proportion of Chinese notices to Chinese declarations is important. Case-by-case skepticism by CFIUS toward Chinese purchasers will often cause them to submit long-form notices to avoid rejected declarations, but some Chinese companies still escape notice review by simply submitting declarations. As demonstrated in the Wyoming missile silo example, there are even Chinese companies that, without CFIUS’ detection, evade review entirely by not submitting documentation.

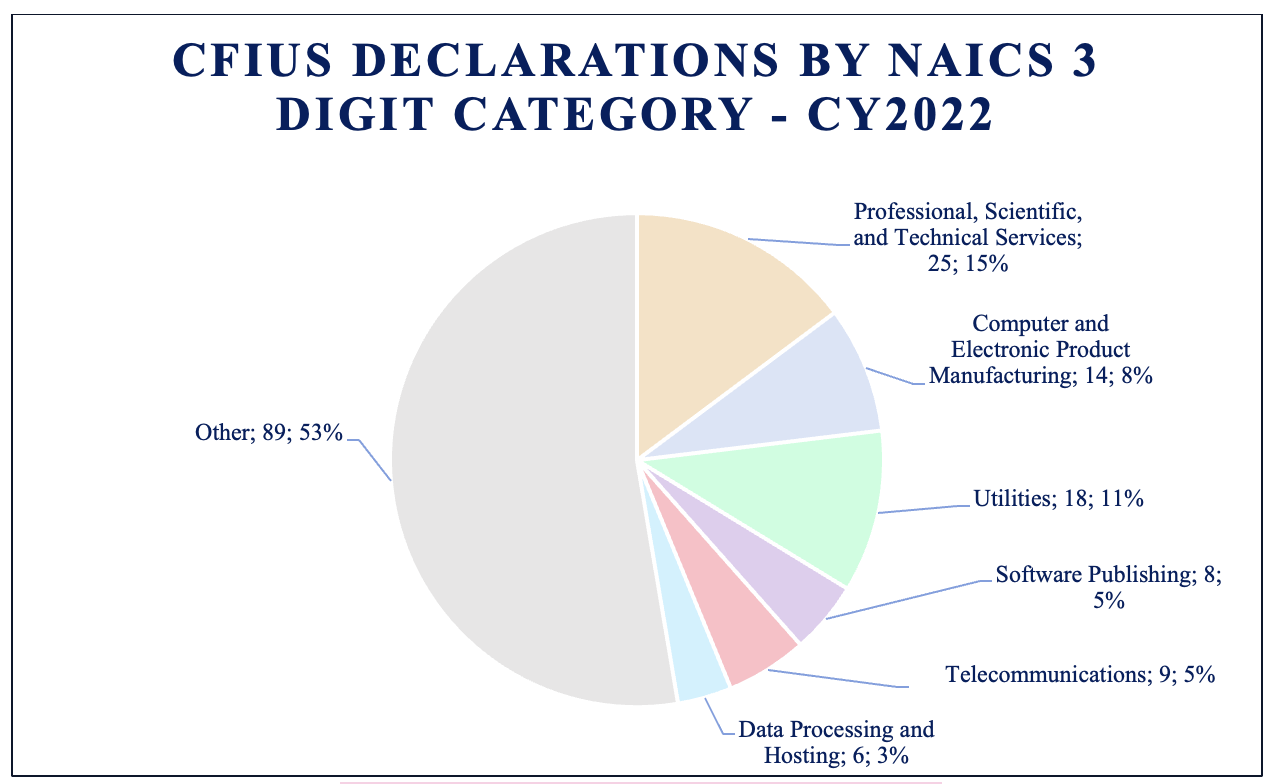

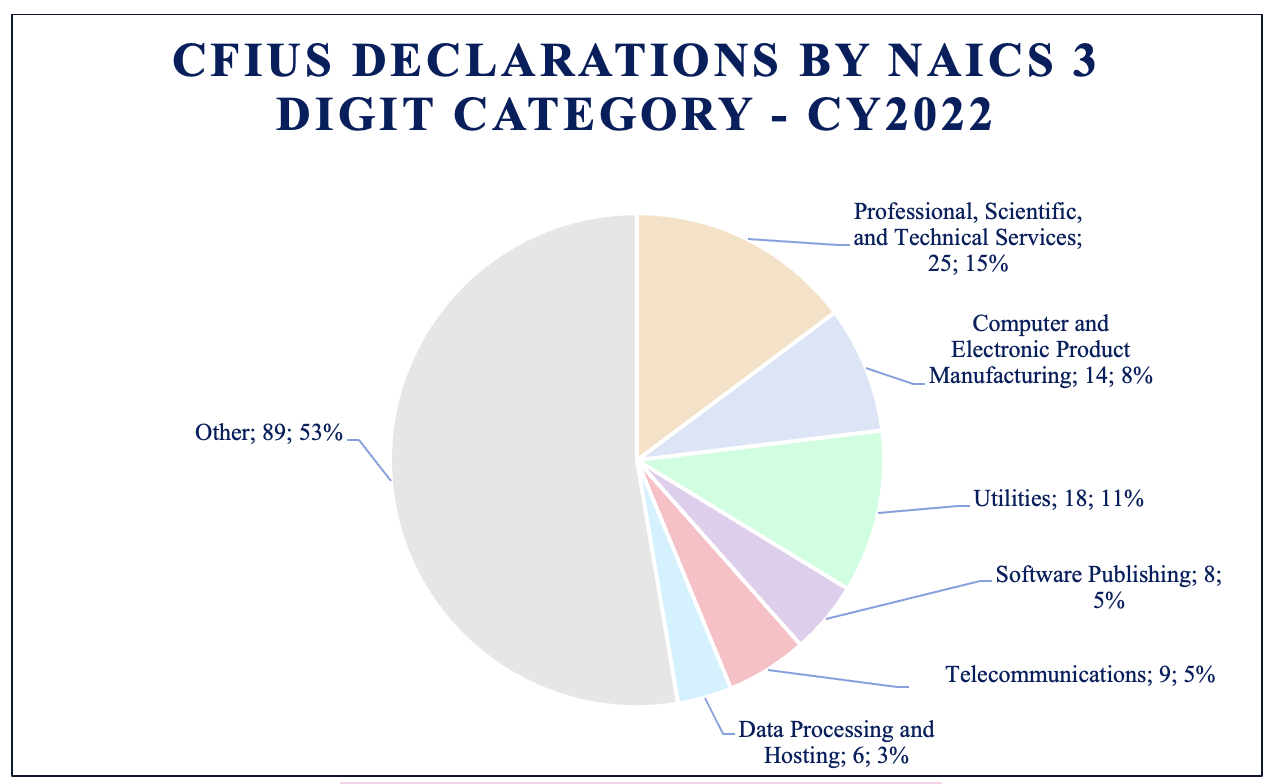

Examining the categories of purchases reveals potential national security vulnerabilities affecting infrastructure, manufacturing, and communications. While specific companies or stock listings are not disclosed to the public, the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) numbers are available for the sectors in which the purchases occur. The totals for the short-form declarations show a particular focus on certain sectors: Of the 154 declarations, 25 were in “professional, scientific and technical services,” 18 were in “utilities” (of which 15 were in “electric power generation”), 14 were in “computer and electronic product manufacturing,” nine were in “telecommunications,” and eight were in “software publishing.” Comparisons of these statistics to their proportional representation in the broader U.S. economy can be found in Figure 7 on page 19.

The six categories found in Figure 5 below make up just under half of the declaration acquisitions filed in 2022, with a myriad of smaller categories (more than 100 NAICS codes are listed as having transactions in the last three years of CFIUS review) making up the other half. Chief sectors of concern include utilities, where control of water or electricity from foreign firms is problematic, and publishing, where control of software content by foreign companies who might implement back doors (as has been explored previously with TikTok) would be dangerous.

When examining long-form filings (“notices”), the numbers are just as concerning: 66 were in “professional, scientific and technical services,” 30 were in “computer and electronic product manufacturing,” 24 were in utilities, 20 were in “software publishing,” 22 were in “telecommunications,” 12 were in “fabricated metal product manufacturing,” and nine were in “machinery manufacturing.” This is illustrated in Figure 6 below

The main sectors of foreign purchase are similar to the short-form filings: manufacturing of sensitive hardware and electronics, control of electrical systems, publishing of software, manufacturing of industrial products, etc. These sectors are vulnerable under foreign ownership, as disruption or arbitrary changes in service in these sectors have the potential to disrupt American life. This is especially so under ICTS, or information and communications technology security, in the case of data control or publishing.

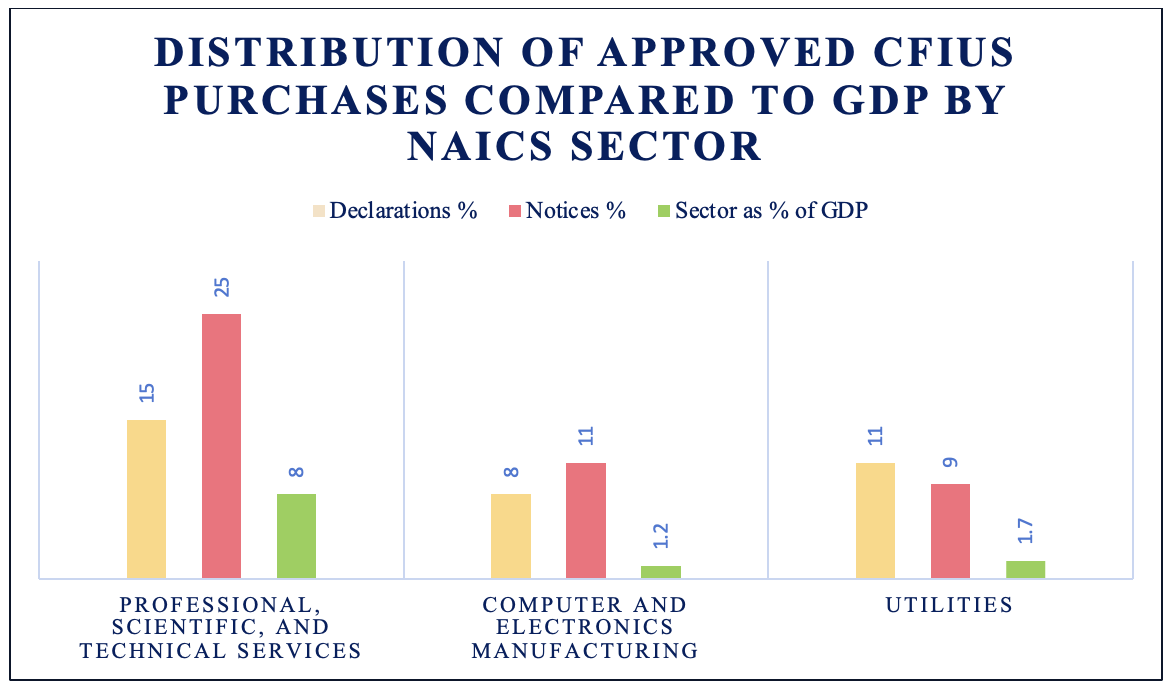

When comparing the share of CFIUS declarations and notices to the share of the economy as a whole, several disparities emerge, as seen in Figure 7 below.

For example, the computer and electronics manufacturing sector, which is susceptible to the insertion of hardware vulnerabilities, is overrepresented by a factor of six in declarations and nine in notices. The utilities sector, including power generation and distribution, gas distribution, and sewage and water supply, is vulnerable to deliberate service disruption and sabotage. This sector is overrepresented by a factor of six in declarations and five in notices.

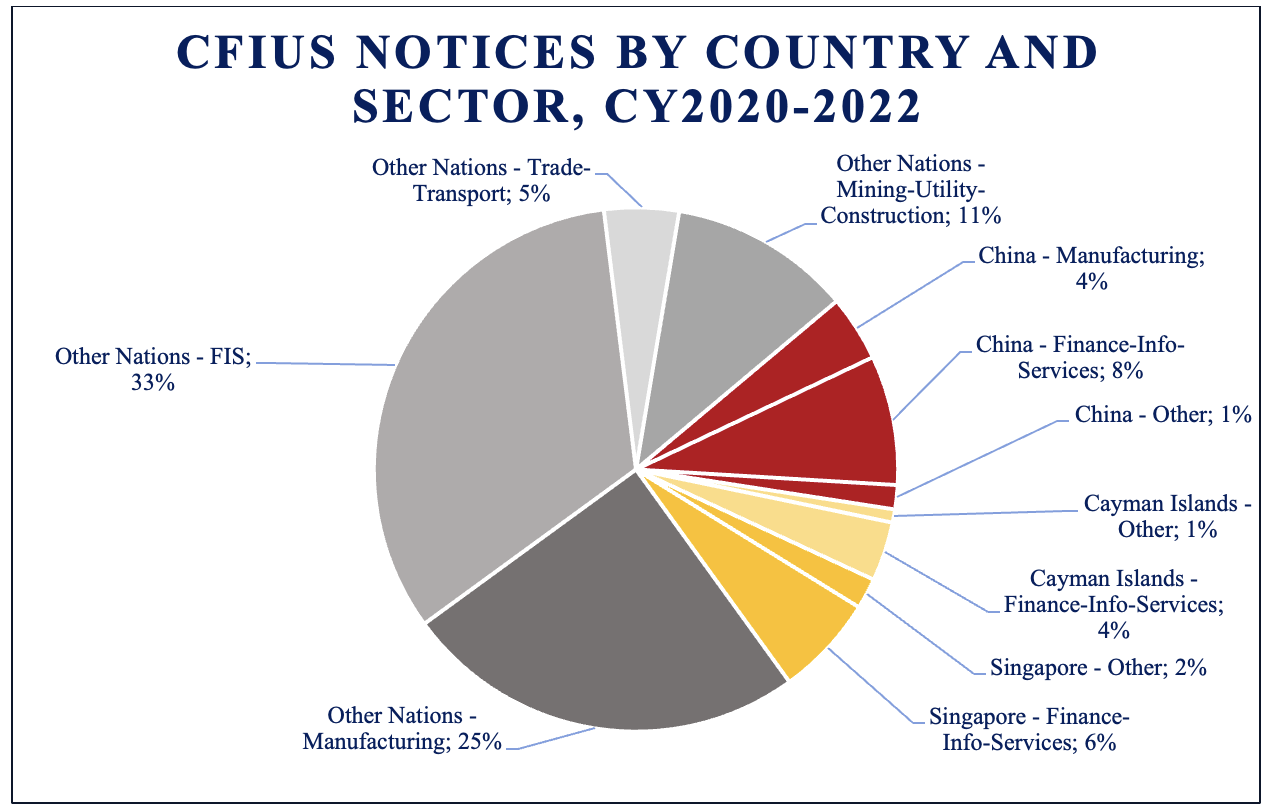

Each report also provides a broad view of purchases by country. CFIUS’ reporting splits the data into four categories: manufacturing, finance/information/services, mining/utilities/construction, and trade/transportation. The results from 2020 to 2022 are presented in Figure 8 below.

For the calendar years 2020–2022, just over one-fourth of all transactions made through CFIUS notices have been made by China, the Cayman Islands, or Singapore.

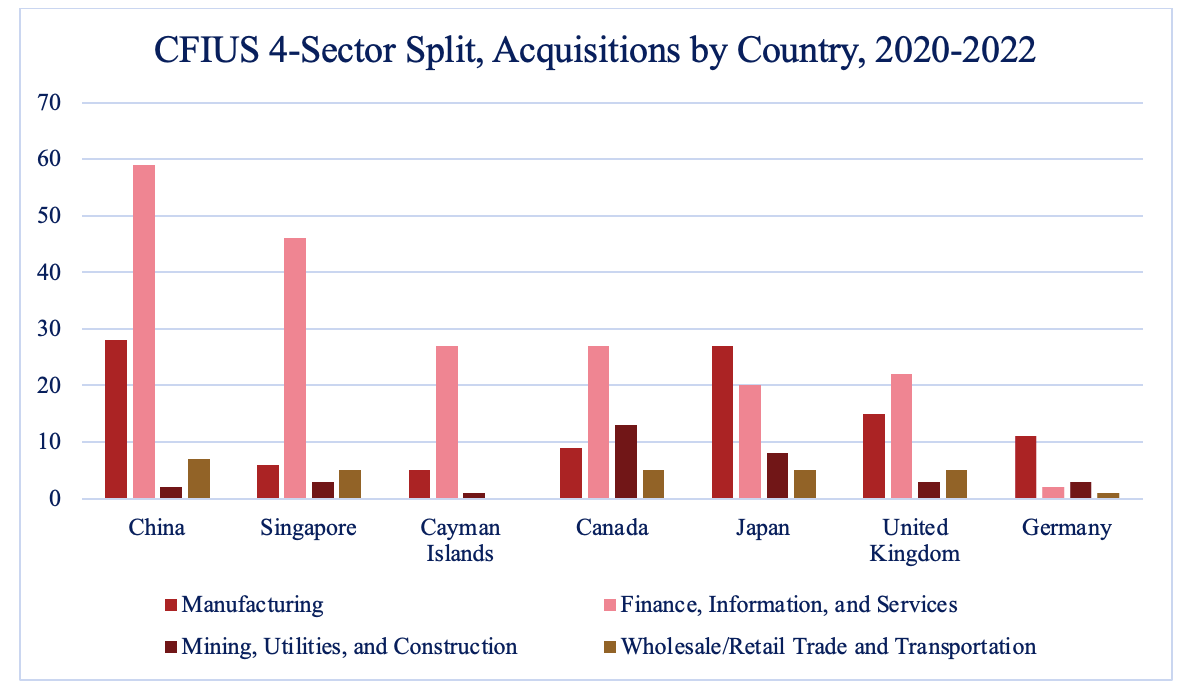

A drill-down in the sectors by country shows a disproportionate acquisition of manufacturing and finance, information, and services companies by Chinese interests. This is illustrated in Figure 9 below. Other top purchasing countries are shown for perspective.

Recommendations

The CCP’s malign intent and access to plentiful capital make it a unique threat that requires extraordinary vigilance. Protecting our sensitive corporate entities, critical infrastructure, and citizens’ personal data must be part of a comprehensive national security posture to combat CCP penetration.

CFIUS, codified by FINSA and augmented by FIRMMA, has undoubtedly prevented many serious security breaches, and the efforts of the Committee and supporting agencies are to be commended. However, congressional and executive reforms, including a series of rule changes and internal policy changes, are required to make CFIUS a comprehensive tool to meet the challenge of the CCP.

We recommend the following:

1. CFIUS must adopt a list of countries of concern in line with lists developed by the Department of Commerce, Department of Defense, or both. These designations should be informed by lists such as 15 C.F.R. § 791.4, developed by the Department of Commerce, which includes the following nations and regimes:

- The People’s Republic of China, including Hong Kong

- The Republic of Cuba

- The Islamic Republic of Iran

- The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)

- The Russian Federation

- The Republic of Venezuela under the control of Nicolás Maduro

2. China, as well as other nations that might be identified as serving as fronts for purchasing American companies with foreign capital, should be restricted from submissions through the declaration process. True ownership and capital origin must always be determined before a purchase is approved. Although few purchases from these nations are permitted through the declaration process, that number should be zero. Any potential commercial acquisitions of American businesses by a hostile nation or its citizens should receive comprehensive treatment.

3. Data requirements and onshoring requirements should be aggressively enforced through mitigation measures. The ongoing failures of TikTok’s Project Texas as a weak negotiated settlement between the Biden Administration and ByteDance exemplify this. Companies that traffic in significant amounts of consumer data—commercial, personal, or genetic—should be required to maintain that data entirely in the United States. Access from overseas should be forbidden and aggressively policed, with severe financial and legal penalties for violations. In essence, a foreign company would be required to establish a subsidiary exclusively accessible from inside the United States dedicated to storing user data.

4. Foreign investors seeking to purchase commercial entities in the United States should not be entitled to comprehensive due process. CFIUS is a creation of the executive branch. Currently, cases that require presidential determinations are not subject to judicial review. That same exemption should be extended to all CFIUS reviews. As stated above, if due process is not granted during presidential decisions, that same due process exemption should be extended to the entire decision-making process.

5. Additions such as further restrictions on physical property and proximity to military installations should be considered as an additional level of physical security. Suggestions made by the House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party should be adopted as remedies. Members of the Select Committee introduced legislation to require screening of all land purchases of foreign adversarial nations and mandating filings for transactions concerning all land near sensitive sites.

6. The list of sensitive sites, as defined in the Appendix of 31 C.F.R. § 802, must be simplified and made far more comprehensive. The current model of individually designating sensitive sites and adjacent lands is insufficient and unwieldy. Sensitive sites must be defined categorically to include military installations, flight paths, firing ranges, and facilities operated by the Department of Defense or the intelligence community.

7. Oversight might be enhanced by adding members to the Committee, such as the Secretary of Agriculture, for greater compliance and awareness of foreign ownership of rural land. Cooperation with state governments in this regard should be encouraged.

Works Cited