Putting Public Safety First: The First Step Act of 2018

Key Takeaways

The First Step Act tackles the revolving door in and out of prison through more robust rehabilitation and a shift from passive release to earned release.

Early evidence finds a large reduction in recidivism from the First Step Act, taking America closer to a new era of safer streets and fewer people in prison.

The First Step Act is part of a broader public safety first approach to restoring law and order through evidence-based reforms to the criminal justice system.

After decades of improvement, crime rates have deteriorated dramatically in the past few years, shaking Americans’ confidence in their ability to go about their daily lives safely and without fear. Homicides alone increased by 34% from 2019 to 2022 (Rosenfeld, Boxerman, & Lopez, 2023). Calls by progressive activists to strip private citizens of their Second Amendment rights, defund the police, and forgo prosecution of criminal activity are out of touch with the reality of high crime and directly undermine efforts to restore public safety. The social justice approach to public safety delivers neither safety nor justice. As one might expect, being soft on crime by making illegal activity free of consequences is a recipe for more crime and less safety.

However, the opposite of soft-on-crime policies is not to simply make prison sentences as long as possible and hope that the mere passage of time will cause prisoners to be reformed citizens once they re-enter society upon serving their sentences. Every year, about 600,000 people are released from state and federal prisons, in many cases with little rehabilitation and a high likelihood of re-offending. Making prison sentences a few years longer by itself does little to reduce the likelihood that a prisoner reoffends—it just delays their potential return to a life of crime and may even increase the odds of becoming a career criminal. But why do we release people from prison if the probability of re-offense is high? Because for both Constitutional and moral reasons, our justice system cannot impose open- ended sentences on people based on the suspicion of what they might do in the future. That approach is reserved for totalitarian regimes and Hollywood movies like Minority Report. Sooner or later, the vast majority of prisoners will be released from prison. Tackling crime effectively means elevating respect for the rule of law, taking dangerous criminals off the streets, and changing the culture of prison to increase rehabilitation and encourage earned release instead of unearned, passive release.

As things stand, the United States already has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world but employs fewer police per capita—a questionable prioritization of criminal justice resources (CEA, 2016). To tackle crime and restore law and order, public safety policies must take a comprehensive, evidence-based approach to deterrence and rehabilitation that discourages people from committing their first crime and prepares ex-convicts to succeed once they re-enter society.

The effectiveness of public safety policies is not measured by the ranks of the incarcerated. Emptying prisons and neglecting to enforce the law certainly do not improve public safety, but fuller prisons do not always make for safer streets either. Instead, a public safety first approach means discarding bumper sticker slogans and subjecting all criminal justice policies, including policing, prosecution, sentencing, prison programming, parole, and the reintegration of ex-offenders back into society, to the test of whether they most effectively reduce crime and restore safety. Evidence suggests that trying to deter criminal activity with the threat of ever-longer prison sentences falls short amidst ongoing underinvestment in law enforcement that leads criminals to believe they will never get caught in the first place. Shifting the paradigm from ramping up the severity of consequences to increasing the certainty of consequences—with active efforts to rehabilitate offenders—offers a more promising path. It is in that spirit, coupled with recognizing that most prisoners are not serving life sentences and that public safety hinges on their successful reintegration, that the federal government passed the landmark, bipartisan First Step Act in 2018.

Background and Overview of the First Step Act

The components of the First Step Act (FSA) are aligned toward one primary goal: reducing recidivism, which refers to ex-offenders returning to criminal activity after their release from prison. The task is urgent. A study of offenders who were released from state prisons in 2012 found that 62% of offenders were rearrested within five years, and 46% of released offenders ended up back in prison (Durose & Antenangeli, 2021). Among prisoners aged 25–39 at their date of release, the rearrest rate was 74%, and the rate climbed to an astounding 81% for those 24 or younger at release. Given that some individuals were arrested multiple times, this troubling rate of recidivism translated to 1.1 million arrests among the 408,300 prisoners who were released in 2012. Moreover, a separate analysis has found that parole violators account for more than one-quarter of prison admissions (Hawken & Kleiman, 2016).

Congress embraced the importance of reducing recidivism when it passed the First Step Act in 2018 by resounding bipartisan majorities in both the House and Senate. The three major pillars of the First Step Act are:

- Tailor prison programming to the assessed needs of individual prisoners to better prepare them for life after prison and reduce the risk of recidivism.

- Incentivize prisoners to participate in prison programs by enabling the lowest-risk offenders to earn credit toward faster transfer to pre-release custody or supervised release. Prisoners convicted of more serious crimes who are ineligible for early release (which, for ease of writing, refers to pre-release custody and supervised release throughout this report) can still earn other benefits that reward participation.

- Pave the way for these incentives by better tailoring the application of mandatory minimums in sentencing guidelines, focusing on serious drug felonies and serious violent felonies.

Prisoner Risk Assessment

To operationalize the corrections reforms in pillars one and two, the FSA requires the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Bureau of Prisons (BOP) to develop a risk and needs assessment system that evaluates prisoners for their individual recidivism risk and assigns them to tailored, evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and to productive activities that maintain low recidivism risk.

To comply with the FSA, the BOP developed the Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risks and Needs (PATTERN), which classifies prisoners as posing a minimum, low, medium, or high risk of recidivism based on a rubric that includes both static and dynamic factors. Static factors are immutable and include an offender’s history of violence. By contrast, prisoners can engage in behaviors that improve their dynamic factors—such as completing education or drug programming—thus lowering their overall assessed recidivism risk. As of November 2020, PATTERN assessed 15% of the BOP population at minimum risk, 32% at low risk, 20% at medium risk, and 33% at high risk of recidivism (Samuels & Tiry, 2021).

Evidence-Based Recidivism Reduction Programming

Regardless of a prisoner’s PATTERN score, certain criminal convictions—such as those for violent crimes, terrorism, espionage, human trafficking, and sexual exploitation—render a prisoner ineligible for early release. About half of BOP prisoners fall into this ineligible category (Samuels & Tiry, 2021). For eligible prisoners, participation in evidence-based recidivism reduction programs can lead to the accumulation of earned time credits (ETCs) that facilitate transfer to pre-release custody or supervised release.

Evidence-based recidivism reduction programs aim to promote work skills and develop life skills, such as better communication, coping with rejection, family relationship building, and morals and ethics. Such programs also include substance abuse treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, and trauma counseling. The FSA created an independent review committee (IRC) and tasked it with evaluating the risk and needs assessment system, along with the prison programming, to ensure adherence to rigorous evidence-based standards.

The FSA requires the BOP to expand recidivism reduction programming to allow all prisoners to participate, regardless of their eligibility for early release. High- and medium-risk prisoners receive placement priority for the programs to allow them to improve their PATTERN score, while the focus for low-risk prisoners is on productive activities that maintain their low-risk status. Prisoners then receive regular assessments to determine if their risk status has changed, which then dictates potential changes to their program participation.

Incentives for Prisoner Participation

Even for prisoners ineligible for early release, the FSA sets forth benefits for participation in the above programs. These can include additional phone privileges, more visitation, transfer to a facility closer to a prisoner’s home, and other incentives. Prisoners eligible for early release can also earn 10 days of time credits for every 30 days of program participation. Moreover, minimum- and low-risk prisoners who complete recidivism reduction or productive activities programs while maintaining or improving their risk score across two consecutive assessments can earn up to five more days of credits for every 30 days of participation.

Prisoners do not reach eligibility for pre-release custody until they have accumulated time credits equal to the remainder of their prison term. In addition, they must have shown a reduced risk of recidivism or maintained minimum or low recidivism risk status during their term. The warden also has some discretion to determine that prisoners would not pose a danger to society if transferred to pre-release custody, are unlikely to recidivate, and have made good-faith efforts to reduce their recidivism risk through program participation. Prisoners who are required to serve a period of supervised release after their prison term may transfer to that release after accumulating sufficient time credits, assuming their latest assessment shows that they exhibit a minimum or low recidivism risk. James (2019) provides additional details and stipulations for early release, including a discussion of the consequences prisoners face if they violate the conditions of their pre-release custody. In particular, if a prisoner commits a new crime (as distinct from a technical parole violation), the BOP must revoke that person’s pre-release custody.

Sentencing Reforms

To further enhance the potency of incentives to participate in the recidivism reduction programming, the FSA includes several reforms to sentencing practices, beginning with changes to the use of strict mandatory minimum sentences. Specifically, the FSA narrows the application of mandatory sentences from applying to all drug felony offenses to applying only to serious drug felonies; it also expands the application of mandatory minimums to include serious violent felonies, whether or not they involve drugs (Breyer, Reeves, Cushwa, & Wong, 2020). Moreover, the FSA reduces the 20-year mandatory minimum to a 15-year mandatory minimum for offenders with one prior qualifying drug conviction, and it reduces the life sentence mandatory minimum to a 25-year mandatory minimum for those with two or more prior convictions.

In addition, the FSA restricts stacking, which allows multiple convictions from a single case to trigger the stricter 25-year mandatory minimum. The FSA also expands the safety valve eligibility criteria, whereby judges have discretion to sentence low-level, non-violent drug offenders to prison terms shorter than the mandatory minimum.

Last among the major sentencing reforms, the FSA gives courts authority to apply the Fair Sentencing Act retroactively and gives prisoners the ability to apply for compassionate release—the latter of which can result in either a reduced sentence or supervised release with or without conditions. Offenders who violate the conditions of their supervision return to BOP custody. To be considered for compassionate release, the offender must be at least 70 years old, have served at least 30 years, be deemed not a danger to society, and fall into at least one major category that is considered an “extraordinary and compelling reason” for a sentence reduction.

Select Other Provisions

The above description is not an exhaustive compendium of provisions in the FSA. Other provisions include a requirement for the BOP to provide a secure storage area for qualified law enforcement officers to store firearms, thereby facilitating their self-defense while safeguarding the correctional environment. The law also prohibits using restraints on prisoners giving birth (except when such prisoners are a flight risk or pose an immediate danger), provides de-escalation training to officers, and expands prisoner employment through the Federal Prison Industries. Importantly, the FSA also reauthorized the Second Chance Act of 2007, which included grant programs for career training, substance abuse treatment, community-based mentoring, and more.

Public Safety First Principles Behind the First Step Act

The FSA springs from a public safety first approach to criminal justice policy that makes crime reduction the standard against which all reforms are judged. It differs from criminal justice policies that place retribution, restoration, or any other value above the simple test of whether a reform will make America’s streets safer. Subjecting policies to this test requires straying from all preconceived notions and articles of faith about the optimal severity of punishment and instead letting rigorous evidence be the guide.

The origins of the conceptual framework behind a public safety first criminal justice policy can be traced to Becker (1968). In a seminal work, Becker challenges the notion that the decision to engage in crime is a purely irrational and impulsive act falling outside the scope of analysis. Instead, he posits a framework whereby criminal behavior resembles decisions individuals make in other contexts, which are shaped by their perception (however skewed) of expected costs and benefits—psychic, pecuniary, and otherwise. A wealth of subsequent empirical research confirms the validity of Becker’s framework. Note also that if Becker is wrong, and if criminal behavior is a wholly unpredictable byproduct of uncontrollable deviant impulses, then the only way to reduce crime successfully is to lock up offenders for as long as possible to ensure their inability to commit further crimes.

The act of taking criminals off the streets in this manner is called incapacitation, and it must undoubtedly be an important component of criminal justice policy. However, if one views crime through the lens of Becker, then the criminal justice policy stool takes on two additional legs—deterrence and rehabilitation—that rely on altering the opportunity cost of crime in order to influence behavior and reduce the commission of crime in the first place. To achieve greater public safety under an incapacitation-only framework, the ranks of the incarcerated must necessarily swell, whereas, with deterrence and rehabilitation as part of the criminal justice arsenal, one can have both lower crime rates and fewer people in prison.

Evidence-Based Deterrence

Few would dispute the importance of deterrence in the abstract, but wide disagreement exists on how to achieve it in practice. The movement to defund the police has not explicitly articulated a coherent view of its own on the role of deterrence. However, its rhetoric seems to downplay the well-established idea that negative consequences for committing crimes deter lawbreaking. Advocates of defunding the police perpetuate the idea that individuals engage in crime only out of material or psychological desperation and thus effectively lack the mental agency to behave otherwise. In effect, advocates deny the efficacy of punishment as a deterrent—claiming that criminals have no choice but to act that way in light of the pervasive social injustice afflicting them. This radical worldview undergirds the activist campaign to take police off the streets and replace them with mental health counselors. While there is little doubt that America is suffering from a mental health crisis, that fact does not absolve people of individual responsibility, and it does not rebut the compelling evidence showing that the threat of consequences does deter crime.

The damage caused by the defund movement’s efforts to stigmatize law enforcement and tolerate supposedly low-level crime is readily apparent in the dramatic rise in organized retail theft over the past few years. Rigorous studies have confirmed the devastating real-world impacts of de-policing, finding significant increases in homicides and total crime (Cassell, 2020; Devi & Fryer, 2020; Piza & Connealy, 2022). Whether such de-policing is explicit policy or is the result of police pulling back in the face of stigmatization (Cheng & Long, 2022), the verdict from the data is clear: When police are missing from the front lines, public safety suffers.

To admit the obvious—that holding criminals accountable deters crime—does not imply that all consequences are equally effective deterrents. Conceptually, increasing either the likelihood that offenders face consequences or the severity of those consequences will act as a deterrent to criminal activity. However, an extensive body of research finds that offenders respond more to the immediate prospect of consequences than to penalties that are either ambiguous or occur down the road (Nagin, 2013). Stated another way, “random draconianism is a bad substitute for swift, certain, and fair responses to misconduct” (Hawken & Kleiman, 2016).

Consider the hypothetical scenario of extending a mandatory minimum sentence from 15 years to 20 years. The marginal deterrent effect of this change is the five years of additional prison time tacked on 15 years down the road. For this change to dissuade criminal activity in a manner that the original 15-year minimum might fail to do, would-be offenders would have to exhibit a high sensitivity to consequences occurring in the distant future. However, criminals are not often known for their patience and foresight. On the contrary, research concludes that the marginal deterrent effect of extending already lengthy sentences is modest at best (Durlauf & Nagin, 2011). A more effective alternative is to shift from a severity-oriented to a certainty-oriented criminal justice policy regime—for example, by directing more resources to police to increase the probability of apprehension (DeAngelo & Charness, 2012). Raising the visibility of police—both by hiring more officers and by allocating officers in a way that heightens the perceived risk of getting caught—has substantial deterrence value and reduces crime (Durlauf & Nagin, 2011; Evans & Owens, 2007). It is notable that, on a per capita basis, while the U.S. employs 2.5 times as many corrections officers in jails and prisons as the rest of the world, America has 30% fewer police officers (CEA, 2016).

Incapacitation: A Double-Edged Sword for Recidivism

The research is clear that, when assessing the tradeoff between certainty and severity in the design of criminal sanctions, certainty prevails in its potential for deterrence. This line of argument applies most directly to discussions about how best to spend a predetermined supply of criminal justice resources. However, it does not directly rebut the possibility that society ought to double down on both margins through more spending, both on police and prisons. After all, prison has more than just a deterrent effect. It can also take offenders off the streets to stop them from committing more crimes—the incapacitation channel of criminal justice policy. Ignoring the importance of incapacitation by myopically pursuing a smaller prison population for its own sake misses the target and endangers public safety.

Unfortunately, incapacitation can be a double-edged sword with unintended criminogenic consequences, given that prison is very rarely a one-way trip. For the 95% of prisoners not serving life sentences, incapacitation is not forever. Someday, they will emerge from prison and re-enter society. Thus, the experience of prison itself and the effects it has on convicts’ ability to cope upon release from prison matters for their propensity to recidivate. Relative to other sanctions and punishments, lengthy incarceration can even increase crime by placing offenders in an environment where their productive human capital deteriorates and their criminal knowledge increases as they learn deviant behaviors from other convicts (Bayer, Hjalmarsson, & Pozen, 2009; Durlauf & Nagin, 2011; Guler & Michaud, 2018). In other words, the simple intuition that longer prison sentences reduce crime by keeping criminals off the streets for longer is an oversimplification—an overly broad and untargeted use of mandatory minimums could worsen public safety by causing offenders to be released back onto the streets as even more hardened criminals. Whether prison has this criminogenic effect or instead can rehabilitate depends on the programming offered and the incentives prisoners face to participate and engage in good behavior.

The empirical evidence presents a nuanced narrative. One prominent study finds that prison time reduces recidivism risk but that parole boards play a critical role in this outcome. The study analyzed the aftermath of a reform that eliminated parole for certain offenders and found an uptick in disciplinary infractions, lower completion of rehabilitative programs, and higher recidivism rates for these inmates compared to convicts not impacted by the reform (Kuziemko, 2013). Intuitively, eliminating parole gutted the incentive for inmates to engage in good behavior and participate in rehabilitative prison programs. The fact that such programs increase ex-convicts’ odds of success on the outside was apparently not a sufficiently strong incentive to participate—the opportunity to earn parole played a critical role in encouraging program uptake. The study further concluded that eliminating parole for all prisoners would swell the prison population by 10% and, worse yet, would increase the crime rate by exacerbating recidivism.

Other studies also find mixed and nuanced results on whether more stringent incapacitation has positive or negative knock-on effects on recidivism. One recent study found that incarceration reduces rates of reoffending but that these effects diminish with the duration of incarceration (Rose & Shem-Tov, 2021). Adding to this fact is that recidivism rates fall dramatically with age (Piehl, 2016). One important implication is that a budget-neutral redeployment of resources from prisons to police to facilitate higher arrest and conviction rates—that is, capturing more criminals and sending more of them to prison but for less time in select cases—could decrease crime. In short, swift and certain sanctions can deter offending at lower costs to society than relying on long sentences alone (Chalfin & McCracy, 2017).

Another study casts doubt on the efficacy of long prison sentences when they are coupled with collateral consequences—a term that refers to a range of legal and regulatory restrictions ex-convicts encounter upon their release into society. These restrictions often take on an economic nature, such as barriers to obtaining an occupational license needed for many jobs. The study found that combining longer prison sentences with collateral consequences increases recidivism (Doleac, 2023).

The logic is simple, compelling, and completely in line with the earlier framework laid out by Becker. Specifically, if ex-convicts have limited opportunities to engage in legitimate activities to make a living, then the cost to them of returning to crime is lower—they simply have less to lose. In this way, harsher is not always better when it comes to fighting crime. That said, going to the extreme of eliminating prison for first-time adult felony defendants or pursuing indiscriminate large-scale decarceration is a bridge too far and would increase crime (Barbarino & Mastrobuoni, 2014; Muller-Smith, Pyle, & Walker, 2023). Similarly, eliminating long prison sentences entirely would be foolhardy in light of evidence showing that they are an effective deterrent for the most harmful criminals (Mastrobuoni & Rivers, 2019).

The Importance of Rehabilitative Programming

Given that the answer to whether incarceration exacerbates or ameliorates recidivism is “it depends,” the details of prison programming take on greater importance. Unfortunately, no comprehensive evaluation of prison programming yet exists to provide authoritative guidance on which program elements work best. In fact, one of the central provisions of the FSA is to authorize more rigorous investigation.

That said, several studies point to the powerful potential of rehabilitative programming. In a summary of the literature, Byrne (2019) identifies modest reductions in recidivism owing to residential substance abuse treatment. Similarly, prison-based mental health programs using a range of methods, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and group counseling, significantly reduced recidivism. Noted criminologist Byron Johnson has also published extensive peer-reviewed research on the benefits of faith-based prison programs. For example, one study examines the Prisoner Entrepreneurship Fellowship, a faith-based correctional rehabilitation program, finding that those who participated exhibited just a 7% recidivism rate over a three-year period compared to 24% for non-participants (Johnson, Wubbenhorst, & Schroeder, 2013). In a wide-ranging analysis, the Council of Economic Advisers finds considerable variation in the quality of rehabilitative programs—making the evidence-based evaluation in the FSA important. The report suggests considerable upside potential, however, reporting that each dollar of taxpayer money spent on prisoner mental health and substance abuse programs reduces the cost of crime and incarceration by between $1.47 and $5.27 (CEA, 2018). The CEA report finds less conclusive effects for programs that focus primarily on education, which naturally raises an important point: Learning how to “succeed” behind bars is different from learning skills that translate to life on the outside. Model prisoners may not make for model citizens, which highlights the need for further research on program effectiveness.

Quality education, vocational, and job training programs also reduce recidivism and may represent one of the primary mechanisms by which prison time can reduce reoffending rates. In a study using Norwegian data, researchers found that incarceration lowers the probability that an individual will reoffend but that this effect is limited to people who were not employed before their prison sentence (Bhuller, Dahl, Loken, & Mogstad, 2020). For these people, prison exposed them to programs directed at improving their employability. In this way, time spent in prison with a focus on rehabilitation can be a powerful force for future crime prevention. Although the evidence of these mechanisms comes from non-U.S. data, Byrne (2019) buttresses this evidence on the salutary impact of such programs using U.S. studies.

Summarizing Evidence-Based Public Safety First Lessons

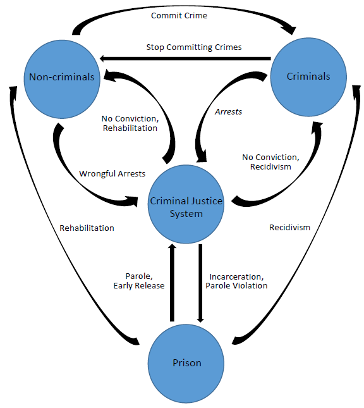

The only core conviction of the public safety first approach is that criminal justice policies exist primarily to protect the public and reduce crime. To effectuate this goal, the evidence must guide reforms. The previous discussion suggests some guideposts, and the flow diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the rich interplay of forces driving the dynamics of crime and the criminal justice system.

Guideposts:

- Effective criminal justice policies must rely on a mix of deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation.

- Swift and certain criminal sanctions have a stronger deterrent effect than marginal increases in the severity of punishment taking place in the distant future.

- The U.S. underinvests in police and could better deter crime by deploying more police resources to increase the probability of apprehension. Such a change would achieve a higher “bang for the buck” than extending prison sentences.

- Incarceration lowers the immediate probability of repeat offenses via incapacitation, but it may either increase or decrease future recidivism. Parole violators account for more than a quarter of prison admissions.

- Rehabilitative programming focused on life skills, education, and job skills is important for reducing recidivism, but prisoners need incentives to participate in such programs, such as the ability to earn early release.

Following these guideposts can reduce the flow of people in Figure 1 into the “criminals” bubble. Deterrence reduces the commission of crime to begin with, while incapacitation prevents repeat criminal activity during a convict’s incarceration period. However, because recidivism represents another path back to the “criminals” bubble, rehabilitation is of the utmost importance. The higher the opportunity cost of crime perceived by both first-time and repeat offenders, the less likely they are to engage in criminal activity. As discussed, a higher opportunity cost of crime is a distinct notion from making sanctions ever harsher. If criminal activity is akin to a permanent scarlet letter that erects barriers to re-integrating back into society, then ex-convicts are likely to see little to gain from staying on the straight and narrow—that is, a low opportunity cost of crime. These insights and guideposts serve as the basis for the FSA.

An Early Look at the Results of the First Step Act

The limited time since the FSA’s phased-in implementation and the disruption of COVID-19 complicate any early evaluation of the law. However, some recent studies provide promising evidence that the public safety first logic undergirding the FSA is coming to fruition in the data.

Accuracy of the Risk and Needs Assessment System

Studies that have assessed the accuracy of the PATTERN system for assigning recidivism risk levels to prisoners rely on a metric called the area under the curve (AUC). The AUC value represents the probability that a randomly selected ex-convict who recidivates after release from prison has a higher PATTERN score than a random ex-offender who does not recidivate. Thus, higher numbers indicate better accuracy.

The first version of PATTERN, which was released in July 2019, had an AUC of 0.8 for the men’s general tool and 0.78 for the men’s violent tool. For women, the numbers were 0.79 and 0.77, respectively. For reference, the criminal justice field considers anything above 0.7 to be good (Samuels & Tiry, 2021). PATTERN then underwent some changes to its risk factors, weighting scheme, and cutoff points for different risk levels. As a result of the changes, 1.9% of men lost eligibility for being able to earn early release because of a recategorization of their risk from low to medium, while 2.3% gained eligibility because of a risk level downtick. The percentages for women were 3.2 and 1.3, respectively.

For reference, the early release eligibility criteria are set to yield a 30% probability of general recidivism and 10% of violent recidivism. Recall that the recidivism rate for ex-offenders as a whole is about 50%. Nevertheless, it is natural to wonder why the thresholds are not set even lower. After all, why should prisoners ever be released early if there is an even moderate chance that they recidivate? The rationale starts with the recognition that these prisoners are not serving life sentences, so they will get out someday, despite the grim recidivism statistics for ex-offenders as a whole. In addition, it is worth recalling the study discussed earlier that established the essential role that parole plays in incentivizing incarcerated prisoners to enroll in rehabilitative programming that reduces their future likelihood of recidivism. Taking these two factors into account, the FSA seeks to reduce crime by transitioning more prisoners into this positive programming through the incentive of being able to earn early release, with the idea being that their recidivism risk after early release is much lower than it would be if they were to be released later without participating in any programs. Choosing never to release these prisoners is not on the table. The criminal justice system does not have the authority—nor should it—to extend prison sentences indefinitely until predicted recidivism risk falls below some tolerable threshold.

The FSA mandates an annual reassessment of the PATTERN system. In addition to testing predictive strength, the assessments evaluate the dynamic validity of PATTERN—that is, the ability of individuals to change their risk designations based on prescribed behavior—as well as its racial/ethnic neutrality. After the first assessment, two changes made to PATTERN were the removal of age at first arrest and whether the individual voluntarily surrendered, as well as the inclusion of two dynamic (changeable) factors—the time since a prisoner’s last violation incident report and the time since the last serious rule violation incident report.

The most recent assessment—conducted by independent researchers and published in a peer-reviewed journal—finds a 0.03 increase in AUCs for PATTERN’s predictive strength relative to the first assessment (Labrecque, Hester, & Gwinn, 2023). The study also finds that prisoners can meaningfully change their PATTERN risk scores. Convicts who lowered their risk scores exhibited less likelihood of recidivating. Lastly, the study arrived at mixed results on the racial/ethnic neutrality of PATTERN, with the algorithm overpredicting general recidivism among Black, Hispanic, and Asian people relative to White individuals but underpredicting violent recidivism for Black males relative to the White reference group. As a caveat, the study explains that “as numerous scholars writing in this space have documented, when base rates of recidivism differ by group as is the case in the current study, it is not possible to satisfy all definitions of racial and ethnic fairness due to competing conceptions of what constitutes bias.” Overall, the authors conclude that “the results of this revalidation study indicate that PATTERN is one of the most accurate risk assessment systems used in the criminal justice system.”

Recidivism

Several studies conducted at different times have assessed the recidivism rates for people released under the First Step Act relative to other ex-offenders. One of the earlier studies reports an 11% general recidivism rate for the FSA based on a 10-and-a-half-month follow-up period. A linear extrapolation to the typical three-year horizon implies a 38% recidivism rate, which is below the 47% rate for the population on which PATTERN was developed. However, it is worth noting that recidivism rates decelerate over time—that is, people who fail tend to fail early (Piehl, 2016). Thus, the actual general recidivism rate for the FSA is likely to be lower than this—perhaps significantly so.

Luckily, one need not speculate because a more recent study has analyzed the latest data (Bhati, 2023). Based on an analysis of 29,946 people released from BOP facilities under the FSA between 2020 and January 2023, the study finds an overall recidivism rate of just 12.4%. While this rate is dramatically lower than the 46.2% recidivism rate for all people released from BOP facilities in 2018, this comparison is not a fair evaluation of the impact of the FSA because the two populations may differ in significant ways. For a better apples-to-apples analysis, the study compares recidivism among those released under the FSA to a group of people released prior to the FSA who had been released for a similar amount of time and who would have received a similar PATTERN risk assessment. The adjusted recidivism rate for the control (i.e., pre-FSA) group was 19.8%. Therefore, the actual FSA recidivism rate of 12.4% represents a marked 37% (7.4 percentage point) improvement. Moreover, of the 20 million arrests made nationally between 2020 and 2022, only 0.02% of them were re-offenders previously released under the FSA. While this number would be 0.00% in an ideal world, one must also consider the many people released under the FSA who did not commit crimes because of the improvements to rehabilitation from the FSA but who would have committed crimes upon their eventual release without the FSA. On net, the drop in recidivism mentioned above translates to 3,125 fewer arrests. The study provides the caveat that it does not prove causality and that future analysis will benefit from more data, but the early signs are positive for the crime-reducing potential of the FSA.

Correctional Officer Safety

Note that, while this piece focuses on the benefits of the FSA reforms for protecting public safety, fostering quality prison programming and incentivizing participation also improves prison safety—especially for corrections officers who put themselves on the line each and every day. Prior to the FSA, prisoners had less of an incentive to engage in good behavior and a weaker support system to equip them with the tools and coping skills to de-escalate conflict and avoid trouble. Although it is premature to say whether the trend will continue, the number of BOP staff physically assaulted by federal prisoners fell by 23% from 2019 to 2022 (BOJ 2021, BOJ 2023).

Conclusion

The FSA represents a landmark effort to restore law, order, and safety to America’s streets by breaking the chain of recidivism that forms a revolving door in and out of prison. The FSA finds its basis in an extensive body of empirical research on the factors that influence criminal behavior, from the deterrent potential of sanctions to the double-edged sword of incapacitation that can increase recidivism unless accompanied by robust rehabilitation and a shift from passive release to earned release. The driving force behind the FSA is that evidence-based prison programming and stronger incentives for participation will lower recidivism by equipping offenders to succeed outside of prison and opening their eyes to life after crime. None of this is to say that the FSA is perfect. The PATTERN risk assessment and needs tool will continue to undergo refinement, just as ongoing analysis will suggest improvements to prison programming. Such inevitable tweaks are not evidence of failure—instead, they are the hallmark of what the FSA represents: a new era of criminal justice policy grounded firmly in evidence-based practices and driven by a public safety first approach. Perhaps most importantly, the FSA cannot be the end of the road for public safety reforms, and it must be applied in a way that recognizes the severity of the ongoing public safety challenges, including the fentanyl crisis—an assault on Americans that is a call to action to marshal law enforcement and criminal justice resources in the most effective data-driven way possible. The message to would-be criminals must be loud and clear: Crime will not be tolerated, actions have consequences, and law and order will never be sacrificed to wayward social justice ideologies that deny Americans the right to enjoy safe streets and to be able to live without fear.

Works Cited