At-Will Employment in the Career Service Would Improve Florida State Government

Key Takeaways

Employees in Florida state government’s career service can appeal dismissals through a process that can take 6 months. However, the legislature made state managers and supervisors “at-will” employees in 2001.

Florida HR directors report these reforms improved state operations.

Other states that made their workforces at-will found doing so made them operate more efficiently. Florida could improve its state government by making all state employees at-will.

Florida’s civil service laws protect state government employees from removal. Most state employees can only be dismissed “for cause.” They can appeal their removal administratively and then in the courts if fired. These removal protections make removing incompetent or intransigent state employees more difficult. Florida partially addressed these problems with the 2001 “Service First” reforms. That legislation made managers and supervisors in state government at-will employees.[1] State Human Resources (HR) directors reported that these reforms improved state government operations. However, union opposition dissuaded Florida from making non-managerial state employees at-will. Other states that have made their entire workforces at-will found it made state government operations more efficient. Florida could make state government work better for Floridians by extending at-will status to all state employees.

Removal Restrictions in Florida State Government

Employees in the Florida state government’s “Career Service” (CS) enjoy for-cause removal protections. Once they pass a one-year probationary period, CS employees may be dismissed only for a “cause” (Fla. Stat. §110.227(1)).[2] If a supervisor believes a CS employee has committed an offense that warrants dismissal, the supervisor must generally provide at least 10 days formal notice.[3] The notice must state specifically what the employee did wrong and the rule or standard violated (Department of Management Services, 2006). The agency must also give the employee an opportunity to respond orally and in writing before dismissing them. Dismissed employees have three weeks after receiving notice to appeal to the Florida Public Employees Relations Commission (PERC) (Fla. Stat. §110.227(5)(a)).[4]

If the employee appeals, PERC appoints a hearing officer who will schedule a hearing within 60 days. Within 30 days of the hearing, the officer submits the case and a recommended outcome to PERC. Either party can file exceptions to the recommendation within 15 days. PERC then reviews the record and may schedule oral arguments. PERC will issue a decision within 45 days of exceptions being filed or oral arguments (Fla. Stat. §110.227(6)). Administrative appeals can thus take 6 months to process (Fla. Stat. §110.227(6)).[5] During appeals, the burden of proof rests solely upon management (Department of Management Services, 2006).[6] If the agency does not meet its burden of proof, PERC can order CS employees reinstated with back pay. If the employee loses before PERC, they can appeal to state courts (Fla. Stat. §110.227(6)(e)). [7]

Service First Ended Supervisors’ Removal Protections

These removal restrictions are a modern innovation. Florida enacted its civil service system in 1967 (Bowman, West & Gertz, 2006, p. 147). In the ensuing decades, governors, legislators, and state commissions repeatedly concluded that the system was making the state government less effective. A 2000 report from the Florida Council of 100, a nonpartisan council of business leaders, documented these shortcomings (2000 Appendix Exhibit 3). They concluded that “[c]urrent restrictions and protections in CS hurt government’s ability to perform … firing underperforming workers takes an inordinate amount of time and paperwork” (2000, p. 9).

The Florida legislature partially addressed these problems two decades ago. The Florida Council of 100’s report proposed systematically overhauling the state workforce, including making all state government employees at-will (2000, p. 22). At-will employees can be fired for any non-discriminatory reason and cannot appeal dismissals. Then-governor Jeb Bush endorsed the Council’s proposal, and the legislature passed what became known as the Service First reforms in 2001. However, strenuous opposition from organized labor prevented Governor Bush from making all state employees at-will (Walters, 2002, p. 32). Instead, Service First moved state managers and supervisors into the at-will Select Exempt Service (SES). The bill streamlined but did not eliminate removal protections for the non-managerial employees who remained in CS (Walters, 2002, p. 34).[8] In total, Service First made about 15 percent of state executive branch employees at-will (Walters, 2002, p. 31).[9] [10]

Service First Successful

Service First succeeded; state HR managers reported that the reforms made state government more flexible. A study a year after Service First passed concluded that “[v]irtually every agency personnel director interviewed expressed the strong opinion that there was life after civil service reform and that it was considerably better” (Walters, 2002, p. 39).[11] Personnel directors reported Service First made taking personnel actions considerably easier (Walters, 2002, p. 35). Interviews with senior HR managers in the Florida Departments of Transportation, Environmental Protection, and Children and Families also reported generally positive evaluations (Bowman & West, 2006, p. 129-30, 134-35, 138).

By contrast, interviews with the supervisors made at-will showed considerably less enthusiasm. A 2003 survey of affected supervisors reported generally low morale (Bowman et al., 2003, pp. 294-295). Subsequent studies found morale improved as supervisors realized the state was not politicizing the newly at-will career positions (Bowman & West, 2006, pp. 130-133). However, these interviews continued to show many managers saw little benefit to being made at-will. As one told an interviewer, “Someone might as well work for business for more money as there is no security in government” (Bowman & West, 2006, pp. 136).

Job security is a benefit to employees, so it is unsurprising state supervisors would prefer to retain employment protections. However, the HR personnel who manage the managers concluded Service First succeeded. A reporter for Governing Magazine summarized their views:

While it's not hard to find critics of Service First in every corner of state government, there is one notable group of long-time Tallahassee denizens who couldn't be more pleased with the new law: department personnel directors who for years have been laboring under the strictures of what they view as an onerous set of rules that have far outlived their usefulness. David Ferguson, head of personnel for the Department of Transportation for the past 30 years, says unequivocally that Service First is the best thing that's ever happened in Florida with regard to personnel administration (Harney, 2010).

Florida has had at-will managers and supervisors for over two decades. During this period, the state government has operated quite effectively. For example, the state rapidly deployed the COVID-19 vaccine to vulnerable populations as it became available.

Expanding at-will Employment to All State Employees Would Improve State Operations

Florida could build on Service First’s success by making the entire CS at-will. The original Service First proposal called for making all state employees at-will, and the version that passed the Florida House of Representatives did so. However, state employee union lobbying persuaded the Florida Senate to limit at-will status to managers and supervisors—employees not eligible for collective bargaining (Harney, 2010). Several other states, including Texas and Georgia, have made their state workforces entirely at-will. Their experience suggests bringing this policy to the Florida government would improve state operations.

Texas, often called the “grandfather of civil-service-free states,” abolished the Texas Merit Council and thus its civil service system in 1985 (Walters, 2002, p. 16). Every employee in the Texas state government currently serves at-will. A survey of Texas HR directors found that they widely believe at-will employment makes employees more responsive to the goals and priorities of agency administrators, provides essential managerial flexibility, helps remove poor performers, and is an essential component of modern government management. Texas state HR directors also report that nearly all separations occur for good cause, and patronage appointments are virtually nonexistent (Coggburn, 2006, pp. 163-69).

Another study of Texas state HR directors reports they “highly value the discretion they receive as a product of the state’s decentralized approach. In fact, there was widespread agreement—even among those respondents lacking in HR expertise—that HR flexibility was key to state agencies’ effectiveness.” Texas HR managers also report “virtually no pressure on them to make personnel decisions based on someone’s political loyalty or lack thereof” (Walters, 2002, pp. 19-21).

Georgia enacted legislation in 1996 that made all newly hired state employees at-will. Almost all Georgia employees serve at-will. State reporting finds managerial abuses of the new system are almost nonexistent.[12]

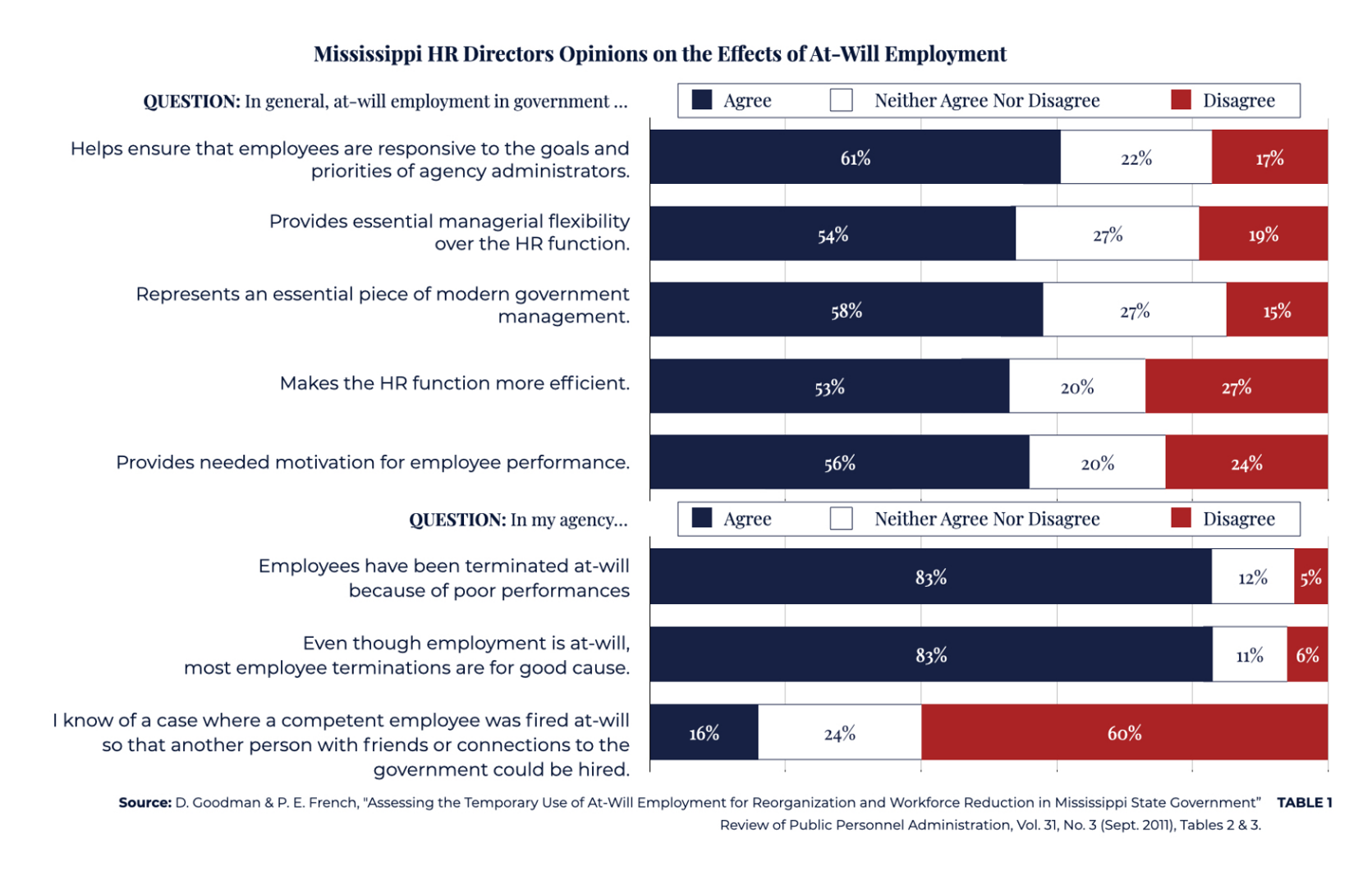

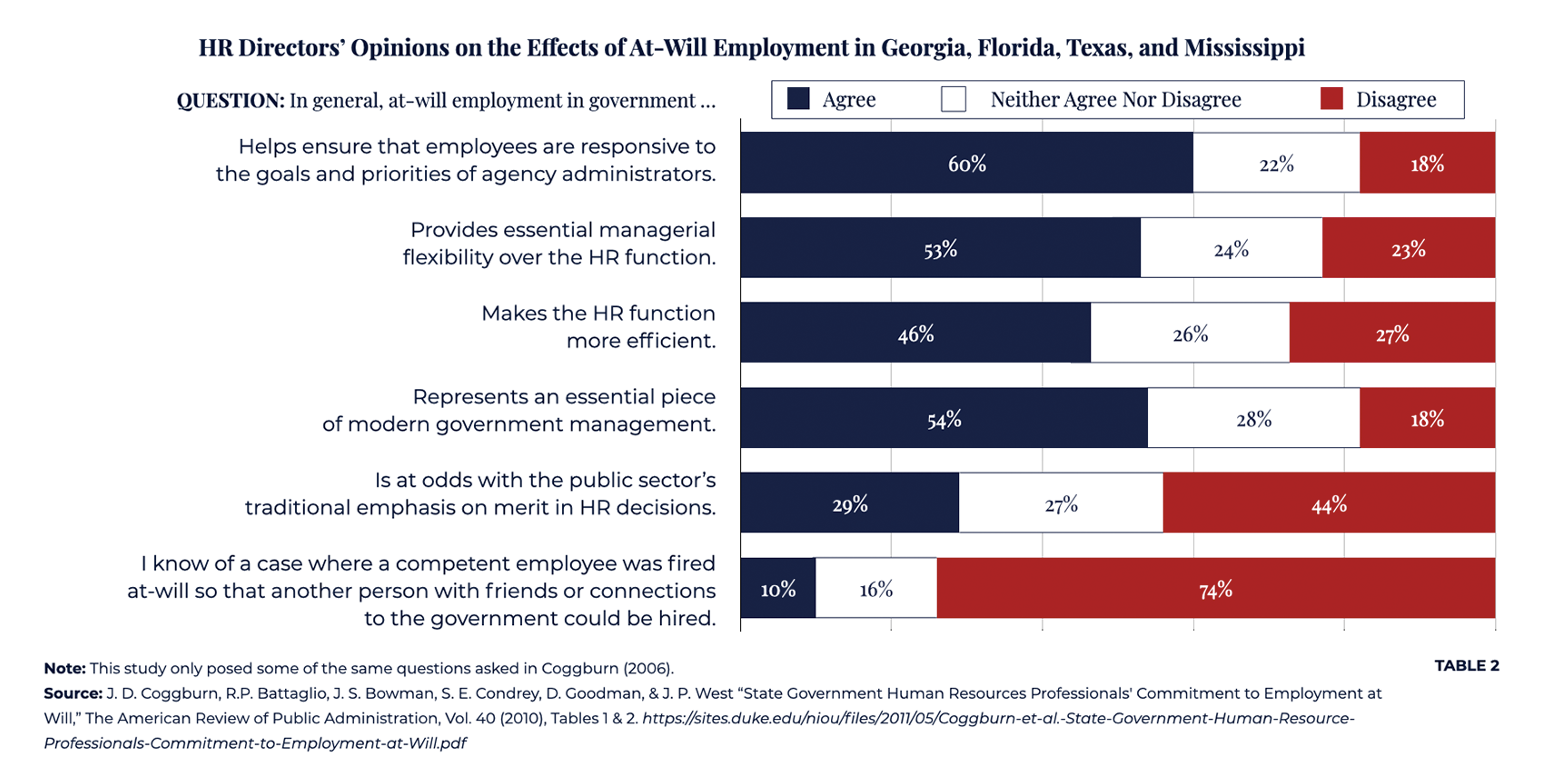

Mississippi has also expanded the use of at-will employment in state government, though most state employees remain covered by the civil service system. Researchers surveyed more than 250 state HR professionals across Florida, Georgia, Texas, and Mississippi about their experiences with at-will employment (Coggburn et al., 2010, p. 196-97). That survey showed these professionals widely believe that at-will employment makes employees responsive to agency administrators’ goals and priorities, make HR more efficient, provides essential managerial flexibility, and provides an essential piece of modern government management. Only 10 percent report knowing of a case where a competent employee was fired at-will to make room for another person with friends or connections to the government (Coggburn et al., 2010, p. 196-97).

States that have implemented at-will employment find that it improves government operations, while feared abuses have not materialized. Florida could realize these benefits across its entire state workforce – not just supervisory positions – by extending at-will employment to all employees. An appendix to this report presents model legislation that would make Florida CS employees at-will.

Conclusion

Civil service protections mean removing Florida state CS employees can take as long as 6 months. Several states have made their workforces at-will. These states’ HR professionals report doing so made state government more efficient, flexible, and responsive to senior leadership’s priorities. At the same time, patronage-type abuses rarely occur.

Two decades ago, the Florida legislature made state managers and supervisors at-will. Florida’s human resource directors also widely report that this change improved government operations. Florida state government could operate more efficiently if all CS employees were made at-will.

Appendix – Model Legislation

Be It Enacted by the Legislature of the State of [State]:

Section 1. This act may be cited as the Public Service Reform Act.

Section 2. [Appropriate sections and subsections] of [State] statutes are amended by:

- Amending [appropriate (sub)section of state code] to read:

An employee may be dismissed for good cause, bad cause, or no cause at all; provided that an employee may not be dismissed for any reason prohibited by law, including but not limited to [section of state code prohibiting racial discrimination] and [section of state code prohibiting whistleblower retaliation].

- By striking [sections of state code that allow employees to grieve or appeal personnel actions outside their agency]

Section 3. This Act shall take effect July 1, 2023.

[1] Fla. Stat. §447.203 (4) defines managerial employees.

[2] Cause is defined to include, but be not limited to, “poor performance, negligence, inefficiency or inability to perform assigned duties, insubordination, violation of the provisions of law or agency rules, conduct unbecoming a public employee, misconduct, habitual drug abuse, or conviction of any crime” (Fla. Stat. §110.227(a)).

[3] In extraordinary situations, such as when the retention of a tenured CS employee would result in damage to state property, would be detrimental to the best interest of the state, or would result in injury to the employee, a fellow employee, or some other person, an employee may be suspended or dismissed without 10 days prior notice (Fla. Stat. §110.227(5)(b)).

[4] PERC is a quasi-judicial state agency. PERC is made up of three commissioners appointed by the governor for overlapping terms of 4 years. One of the commissioners is designated as the chair and serves as the chief executive and administrative officer of the agency. PERC also employs eight hearing officers, who are members of The Florida Bar with more than 5 years of experience (Morton, 2019).

[5] Employees have 21 days to appeal to PERC. The hearing officer schedules a hearing within 60 days and issues a recommended order within 30 days of the hearing. The employee has 15 days to file an exception to the recommended order. If PERC does not grant oral arguments, the agency has 45 days to issue a final order. This adds up to 171 days. If PERC grants oral arguments, the appeals will take longer.

[6] See, for example, Falk v. Scott (2009), where the court explained that “where an agency terminates an employee for certain stated grounds, reason, logic and the law would require that the agency affirmatively carry the burden of proving the essence of its allegations … the fact that the aggrieved employee must initiate a hearing before the Commission or that such action is denominated as an appeal does not alter the proposition that the burden of proving the basis for termination rests with the employing agency.”

[7] Judicial review is only available to “[a] party who is adversely affected by final agency action” (Fla. Stat. §120.68(1)(a)).

[8] For example, the legislation expanded the definition of “cause” for employee dismissal or suspension to include poor performance and any crime other than just those involving unethical behavior; reduced the number of days to complete appeals processes; extended the probationary period from 6 months to 1 year; and eliminated the PERCs ability to mitigate penalties upon appeal.

[9] This figure does not include state university employees or state legislative and judicial employees, who also serve at-will (Fla. Stat. §110.205 (b-d)).

[10] While managers and supervisors now serve at-will, agencies still may not dismiss them for discriminatory reasons. Agency civil rights offices, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the Florida Commission on Human Rights hear discrimination claims. Florida whistleblower protection statutes also protect at-will employees who report fraud or other illegal conduct from retaliatory dismissals.

[11] This report included interviews with state personnel directors in Georgia and Texas—two other states with at-will employment, as well as Florida.

[12] “According to a University of Georgia report on the impacts of Act 1816, there’s been no decipherable pattern of abuses. One experienced personnel director in a large agency reports that he can ‘count on the fingers of two hands the number of questionable hires he’s seen under the current administration” (Walters, 2002, p. 28).

Works Cited