Big Government Reconciliation Bill’s Labor Provisions Undermine Workers’ Freedom

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Congressional leaders want to use the budget reconciliation process to enact sweeping changes in labor law. Reconciliation bills cannot be filibustered and can therefore pass on a party-line vote. Congressional rules limit reconciliation bills to measures that affect taxes or spending. Congressional leaders are trying to fit these labor policy reforms into this framework. If they succeed, the reconciliation bill will severely undermine worker freedom. The reconciliation bill’s labor provisions include:

• Prohibiting staff meetings that discuss union organizing. The draft bill fines employers that hold mandatory staff meetings to discuss union organizing. Employers often use these meetings to educate their employees about the potential downsides of unionizing. Union advocates hope that banning these meetings will make it easier for them to organize firms. But preventing employers from making their case would give workers a skewed perspective. Employees benefit when they hear from both sides before making a major decision.

• Fines for technical ULPs. The draft bill imposes civil monetary penalties of up to $50,000 for each employer unfair labor practice (ULP). The bill also personally subjects business officers to these fines. These fines would apply to all ULPs, not just serious ULPs like firing a union supporter. Since federal labor law is highly complex, this will expose many employers–especially small businesses–to potentially crippling fines for inadvertent violations. This will give union organizers leverage to pressure employers into forgoing secret ballot elections for their employees.

• Tax break for funding union political campaigns. The draft bill provides a $250 above-the-line tax deduction for workers who pay full union dues, including the portion of dues that funds union political activities and lobbying. However, unionized workers who pay agency fees–which do not support political activities–cannot take the deduction. This deduction indirectly subsidizes union political campaigns.

• Tax credit for vehicles made with union labor. The draft bill gives Americans who buy electric vehicles produced by unionized workers a $4,500 tax credit. Americans who buy vehicles made by workers who vote against unionizing could not claim this tax credit. This discriminates against employees on the basis of how they exercise their freedom of association, and encourages employers to deny their employees a secret ballot election before unionizing.

• Attacks independent contracting. The draft bill increases funding for the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division by one-third. This will fund a forthcoming enforcement surge against independent contractors, seeking to reclassify them as employees subject to federal labor laws. Reclassified employees will lose much of the flexibility that independent contracting affords.

• Prohibits lockouts and permanent replacement workers. The draft bill prohibits employers from locking out employees during labor disputes, or hiring permanent replacement workers during strikes. In the short term, this would increase union bargaining leverage. In the long term, it seems likely to lead unions to negotiate contracts that put unionized employers at a competitive disadvantage. This reduced competitiveness could cause unionized employers to shed jobs, further reducing union membership.

• Bans class action arbitration agreements. The draft bill prohibits employers and employees from using arbitration to resolve class grievances, requiring such disputes to go through the court system instead. Arbitration is faster and less expensive than litigation, and also generates far fewer attorney fees. This provision will prevent employees from using an effective and efficient mechanism for redressing their rights, while creating opportunities for trial lawyers.

Current federal law protects employees’ rights to choose whether to unionize. These proposed policies are designed to instead push workers into unions, whether or not they believe it would benefit them. The policies also prevent workers from using systems like independent contracting or arbitration that benefit them. Worker freedom will suffer if the Senate parliamentarian allows these provisions into the reconciliation bill.

Big Government Reconciliation Bill’s Labor Provisions Undermine Workers’ Freedom

Congressional leaders want to use the budget reconciliation process to enact sweeping changes in labor law. Reconciliation bills cannot be filibustered and can therefore pass on a party-line vote. Congressional rules limit reconciliation bills to measures that affect taxes or spending. Congressional leaders are trying to fit these labor policy reforms into this framework. If they succeed, the reconciliation bill will severely undermine worker freedom.

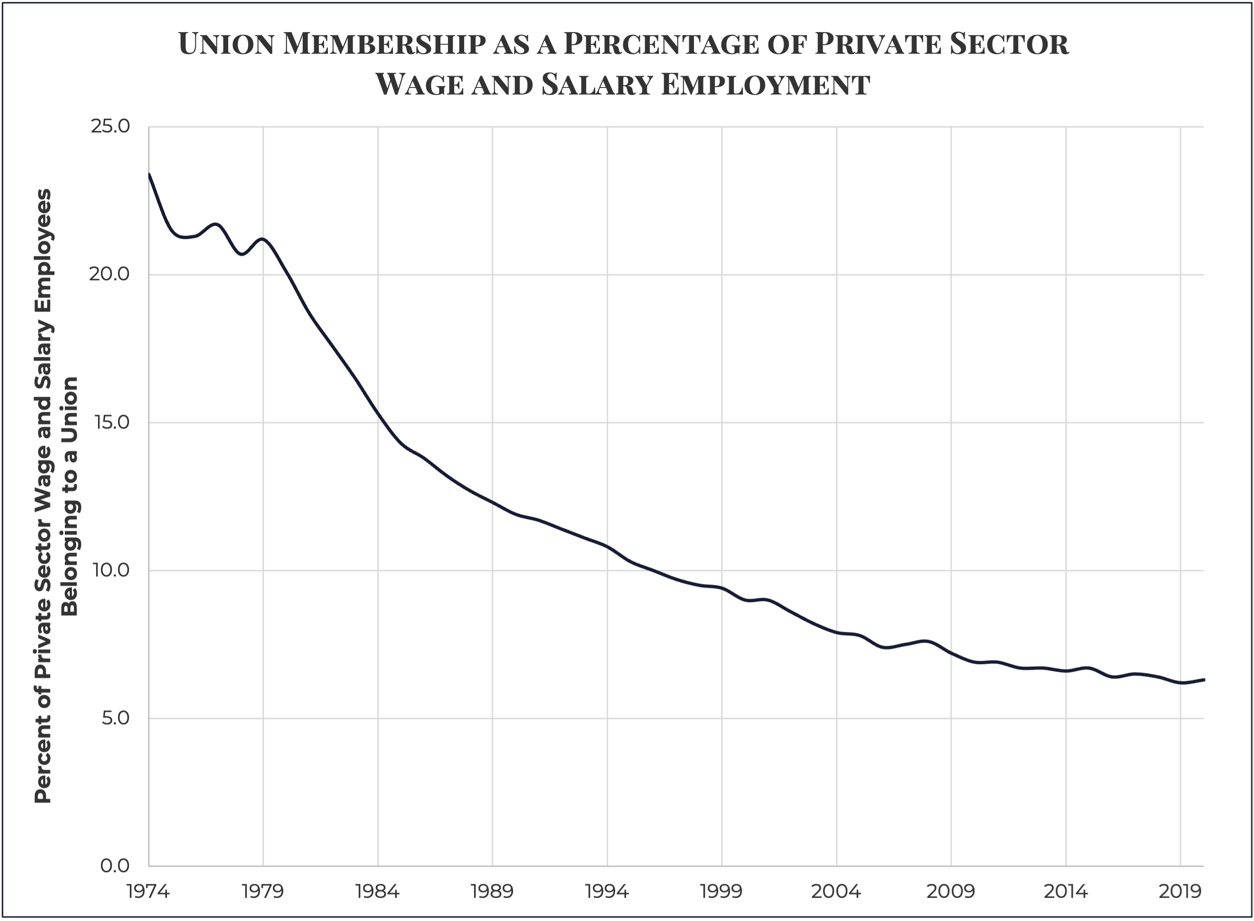

Union membership has fallen sharply over the past half-century. In the early 1970s, a quarter of private sector workers belonged to a union. By 2020, only 6 percent did (Hirsch & Macpherson, 2021). Union membership has largely fallen because unions make the firms they organize less competitive. The average unionized company grows more slowly–or shrinks more quickly–than otherwise comparable nonunion firms (Farber & Western, 2001; Hirsch, 2008). At the same time, research shows relatively few nonunion workers want to unionize (Farber, 1990; Rasmussen Reports, 2009). Researchers find that most employees believe they are on the same team as their employer. Modern workers want to work cooperatively with their company. This limits the appeal of an adversarial collective bargaining model that has changed little since the 1930s (Farber & Rodgers, 2006, pp. 56-58; Hirsch & Hirsch, 2007, pp. 1145-1147). Consequently, unions have not been able to organize enough new workers to replace those lost at unionized firms that shrink or go bankrupt (Farber & Western, 2001; Hirsch, 2008).

Unions would like to increase their membership. However, they have shown little interest in changing their business model to address these challenges. Instead, they have focused on changing federal labor law to facilitate union organizing. In President Obama’s first term, the AFL-CIO pushed to replace secret ballot organizing elections with publicly signed cards. “Card-check” would have forced workers to decide in front of union organizers. This proposal raised widespread concerns about organizers pressuring or harassing workers into joining. Ending secret ballot elections became highly controversial, and the proposal died in Congress (Turl, 2009).

Source: Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson, “Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey,” Unionstates.com, http://unionstats.com/Private-Sector-workers.htm

Unions have now persuaded Congressional leaders to put provisions in the reconciliation bill designed to boost their membership. As Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers explained, “Labor is not only all over supporting it, it has helped craft it” (Mueller, 2021).

There is nothing wrong with higher union membership when workers freely choose it. Federal law gives private sector workers the right to join a union or refrain from doing so. Unfortunately, many provisions in the reconciliation bill are designed to push workers into unions, rather than leaving the choice in their hands. Other provisions would boost union organizing in the short term, while making unionized companies less competitive over the long term.

Unionizing has both pluses and minuses. It can protect workers from corporate abuses. It can also make companies less competitive. Federal law currently gives workers the freedom to decide whether to accept the risks to their employers’ financial health. Provisions in the reconciliation bill undermine that freedom.

WITHHOLDING INFORMATION FROM EMPLOYEES

The National Labor Relations Act’s (1935) guiding principle is employee choice. The bill protects workers’ right to exercise “full freedom of association and select "representatives of their own choosing.”[1] The NLRA makes it an unfair labor practice (ULP) for an employer to punish workers who support unionizing.[2] It prohibits unions from coercing workers who oppose unionizing.[3] The NLRA also provides for the option of government-supervised secret ballot elections when workers organize or decertify a union.[4]

The current standard procedures for union organizing require unions to persuade employees to voluntarily unionize, and employers that want to remain nonunion to persuade employees to voluntarily choose that status. The National Labor Relation Board (NLRB) requires employers to provide union organizers with employee names and addresses (Excelsior Underwear Inc., 1966). Organizers then come to workers’ homes to sell them on the benefits of union representation. The law strictly prohibits employers from communicating with employees at home. Employers instead express their views through staff meetings (National Labor Relations Board, 2017, pp. 349-50). After a short campaign period–typically between 3 and 7 weeks–the NLRB conducts a secret ballot election. If a majority vote to unionize, the employer must begin bargaining. If most workers vote against unionizing, the union must abandon the organizing drive.

The draft House reconciliation bill prohibits employers from holding mandatory staff meetings to discuss unionization. It punishes violations with very steep fines – up to $50,000 per employee who attends each (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, p. 176). This would make it very difficult for employers to communicate their message during union elections.

This change is designed to make it easier for unions to win organizing drives. Union advocates have celebrated how this ban on so called “captive audience meetings” will make union organizing much easier (Campbell, 2020; Magner, 2020; Magner 2021a; Ulin, 2021). But hearing only from one side would make it much harder for workers to make an informed choice. It would give workers a skewed perspective.

Union organizers naturally promote the benefits of unionizing and downplay the risks. Unions train their organizers to deflect topics that make workers less likely to unionize, like strike histories and dues increases (Strengthening America’s Middle Class, 2007). They understandably focus their message on the benefits the union could provide. Employees generally learn the potential downsides of unionizing through employer meetings (Deakins & Wathen, 2009).

A recent article in the left-wing American Prospect illustrates how employer staff meetings help employees cast an informed vote (Dayen, 2021). The American Prospect obtained audio recordings of staff meetings during a United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) organizing drive at No Evil Foods, a plant-based meat alternative manufacturer. The article documents how the company used those meetings to inform workers that:

- UFCW represents employees in meat processing plants that directly compete with No Evil Foods, potentially creating divided loyalties at the bargaining table.

- The former president and secretary-treasurer of the UFCW local seeking to organize them had recently been imprisoned for embezzling over $300,000.

- Thousands of UFCW members have filed ULP complaints against the union for breaching its duty of fair representation.

- The company already offered above-market pay and benefits, and was losing money, so the union had little room to negotiate higher compensation.

- The UFCW accepted significant pay cuts at other establishments it organized, while a number of UFCW-represented firms went bankrupt.

- UFCW’s strike fund only provides $100 a week in strike pay, and striking workers lose their health benefits and cannot collect unemployment insurance.

- The UFCW constitution allows the union to fine members who disobey union directives.

- Top UFCW executives make over $300,000 a year from members’ dues, along with generous perks and benefits.

- UFCW spent $1 million of member dues on a party at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Employees benefit when they get all the information before making a decision–including information the union finds uncomfortable. Unionizing is a significant decision, and difficult to reverse. Under the NLRB’s “recognition bar” and “contract bar” doctrines, employees generally may not remove a union for three to four years after initially organizing.[5] The current system lets workers hear both sides make their strongest case, reflect, and deliberate before they vote.

Most workers in these elections ultimately choose to unionize. NLRB data shows that unions win over 70 percent of organizing elections held.[6] However, a significant number of workers conclude union representation would not benefit them, and vote no. This happened at No Evil Foods. Union organizers initially thought they would win. After the staff meetings employees voted 3-to-1 against unionizing (Dayen, 2021). Preventing employers from providing their employees with additional perspective hurts workers. If a union can only win if employees do not hear the other side, those employees are probably better off without it.

BYPASSING SECRET BALLOT ELECTIONS BY INTIMIDATING EMPLOYERS WITH HEFTY FINES

Provisions in the draft House reconciliation bill also give unions leverage to pressure employers into not requesting a secret ballot election. The NLRA does not guarantee workers a secret ballot election before unionizing. Rather, employers may request a secret ballot election when a union claims majority support. Employers can also recognize the union voluntarily, without asking for an NLRB-supervised vote.

In the 1990s, unions shifted their organizing tactics away from persuading workers in election campaigns and towards pressuring employers to recognize them without a secret ballot election (Brudney, 2004). Union “corporate campaigns” now seek to hurt a nonunion firm badly enough to either convince it to “voluntarily” unionize or to bankrupt it. One union organizing guide explained:

Who do we really need to convince of the advantages of being union? Employees or employers? Organizing is war. The objective is to convince employers to do something that they do not want to do … [o]rganizing without the NLRB means putting enough pressure on employers, costing them enough time, energy and money to either eliminate them or get them to surrender to the union … focus[] on employers and mak[e] them pay for operating nonunion (Crump, 1991, pp. 35-38).

Corporate campaigns deny employees’ choice. They turn the decision to unionize into a question of how badly a union can hurt the employer, not whether the employees want a union. Corporate campaigns enable unions to organize workplaces where few workers support them. Unions understand this. As the former political director of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) explained:

One of the concerns organizers might have about waging economic war on an unorganized company is that it might turn employees against the union. I look at it this way: If you had massive employee support, you probably would be conducting a traditional organizing campaign … You don't need a majority or even 30% support among the employees [in a corporate campaign]. A few people inside and outside are all that's necessary to be successful (Crump, 1991, pp. 42-43).

The draft reconciliation bill substantially increases union leverage for corporate campaigns. It creates civil monetary penalties of up to $50,000 for each employer ULP. It also allows the NLRB to fine corporate officers and directors personally for up to the same amount (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, pp. 172-175).

On the surface, this seems like a minor change, merely strengthening penalties for illegal behavior. However, federal labor law is highly technical and at times counterintuitive. The NLRA prohibits obviously coercive behavior, such as firing workers for supporting a union. But it also prohibits actions that many non-lawyers could assume are unobjectionable. For example, an employer facing a union drive generally cannot ask workers how they feel about the union. Such “interrogation” is a ULP (Swirsky & Stutz, 2017). Neither may employers ask workers why they are dissatisfied and what they would like to see changed. “Soliciting grievances” is also a ULP (Mek Arden LLC, 2017). So is giving workers an unannounced raise during an organizing drive (National Labor Relations Board, 2017, pp. 344-345).

Employers facing an organizing drive often commit technical ULPs. This especially happens to smaller businesses, since they frequently lack in-house counsel to ensure compliance. [7] Current law requires employers to cease-and-desist from prohibited behavior, but generally does not impose serious financial consequences (like paying back wages) unless employers commit serious infractions (like firing a union supporter).

The draft reconciliation bill would make such technical ULPs potentially financially disastrous. The added fines would encourage unions to file over minor ULPs. Union advocates are already predicting that these provisions, if they become law, will substantially increase ULP complaints (Magner, 2021b). The fines would also force businesses to litigate complaints instead of settling them, since correcting the violation would no longer satisfy the law. This would also force businesses to pay substantial attorney fees.

Consider a small business with 50 employees facing an organizing drive. During the campaign the owner asks each employee what they don’t like about the workplace and how it could be improved. That employer has solicited grievances 50 times. A union might normally let minor ULPs like this slide, but the penalties would encourage it to file 50 ULP complaints instead. The small business then faces up to $2.5 million in fines, and up to the same amount again against the owner personally, for a total of $5 million. Defending against the complaints will also potentially cost hundreds of thousands in attorney fees. Those are maximum fines, and the NLRB could seek a lesser penalty.[8] But even an 80 percent reduction still leaves a million dollars in fines, plus attorney fees.

This would give union organizers significant leverage over employers. They can offer to withdraw their ULP complaints and eliminate the employer’s legal liability. In exchange, they would want the employer to accept the union without a secret ballot election. Union corporate campaigns frequently feature exactly such pressure tactics with other legal violations (Crump, 1991, pp. 38-40). Adding $50,000 penalties to each ULP would enable unions to credibly threaten many small businesses with bankruptcy. Notably, the reconciliation bill does not impose similar penalties for technical ULPs on unions–only employers.

These civil monetary penalties advance card-check through the back door. The reconciliation bill does not formally curtail secret ballot elections. But it gives union organizers leverage to pressure employers into not requesting them. Many small businesses, facing massive potential fines, would have no choice but to accept unionization without a vote. If these penalties become law, many workers will be unionized—whether they want union representation or not.

ELECTRONIC VOTING

The House reconciliation bill contains another provision that undermines employee choice: it removes the ban on electronic voting in union elections. NLRB elections currently operates similarly to political elections. In most cases, the NLRB sets up a voting booth on company premises. Employees cast their ballot in privacy, and no one knows how they voted (National Labor Relations Board, 2000). In some cases, the NLRB conducts a mail-in election, which operate similarly to absentee voting. In those cases both employers and unions are strictly prohibited from handling employees’ ballots (Weldon, 2021).

In 2010, the NLRB proposed electronic voting, such as having workers vote by e-mail, text message, or on a website. This produced immediate concerns that it could compromise voting privacy. While workers can vote privately electronically, union organizers can also come to their house and ask to watch their vote. Or unions can host “election parties” where they supervise voting. Even refusing those invitations makes a statement about the employee’s preference (Smith & Carron, 2010). The risks to employee privacy persuaded Congress to prohibit electronic voting in 2011 (Horton, 2021).

The reconciliation bill not only removes this prohibition, it also requires the NLRB to spend $5 million implementing electronic voting (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, p. 167). If it passes, workers will have less privacy when they decide about union representation.

RESTRICTING INDEPENDENCT CONTRACTING AND FREELANCING

The draft House reconciliation bill would also advance the Biden administration’s efforts to restrict independent contracting and freelancing. The bill funds an expected Labor Department enforcement surge against employee “misclassification” and penalizes firms that misclassify workers under the NLRA.

Federal law considers workers either employees or independent contractors. Independent contractors work for themselves. Unlike most employees, independent contracts can usually choose when and where they work. Many workers value this flexibility (Chen et. al., 2017).

The Obama Labor Department greatly restricted independent contracting. An Obama administration “Administrator’s Interpretation” reclassified many independent contractors as employees of the companies they contract with. For example, the interpretation generally treated contractors who perform work integral to a firm’s business as employees (Bannon, 2015; Santen, 2015).

This approach would have converted many freelance workers into employees of the companies they contract with. It would have particularly affected the gig economy, converting virtually all rideshare drivers into employees. These workers would have lost the flexibility that independent contracting brings, such as being able to set their own hours and work with multiple companies. The Trump administration rescinded the Obama interpretation shortly after taking office, and issued regulations codifying the traditional test for employment or contracting.

Several state legislatures subsequently redefined independent contracting under state labor law. Most prominently, in 2019 California passed AB 5. AB 5 codified the restrictive ABC test for self-employment (National Law Review, 2020).[9] That test is similar–though not identical–to the standard DOL proposed. AB 5 badly hurt self-employed Californians. Many organizations could not work with freelancers if they had to adhere to expensive labor regulations. Community theaters closed, youth athletic programs were cut, and music festivals were canceled (Steiner, 2019; Joseph, 2020; Grimes, 2020).

AB 5 especially hurt disabled Californians (Biro, 2020). Many employees with disabilities cannot work in a traditional job and need the flexibility of working from home and picking their own hours. Unfortunately, AB 5 sharply restricted these opportunities. Their caregivers also often need to work from home and control their schedule. They could not do this under AB 5. As one California mother explained:

AB5 is why I had to pack up my very ill husband with stage 4 cancer and autistic son and leave the state. There is no way I can take care of our family and work a ‘traditional’ type job. I have always worked for myself and paid my taxes. I was terrified of becoming homeless (Morales, 2020).

The California legislature quickly recognized that AB 5 was hurting workers. Less than a year after passing it, they exempted dozens of occupations from its coverage (Rivera et. al., 2020). A few months later, California voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot initiative returning rideshare drivers to independent contractor status (Ballotpedia, 2020).

The Biden administration is now resurrecting the Obama administration’s campaign against independent contracting. Biden’s Labor Department rescinded the Trump administration’s independent contractor rule (Independent Contractor Status, 2021). President Biden has re-nominated David Weil to head the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD)–the same role he held under President Obama. Weil was the architect of the Obama administration’s policies restricting independent contracting. He is widely expected to resume his legal activism against this business model (Penn, 2021). When that happens, it will bring AB 5-type policies to the entire economy. The Labor Department could reclassify millions of independent contractors–including most “gig economy” workers like rideshare drivers–as employees. These employees would lose the flexibility of working for themselves.

The draft reconciliation bill would facilitate these efforts by increasing WHD’s budget by $400 million over the next five years (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, p. 166). This represents a one-third increase in the agency’s budget.[10] This funding would allow Weil to aggressively pursue cases against companies alleged to have “misclassified” workers under the Labor Department’s forthcoming standard.

The Biden NLRB is similarly expected to issue rulings redefining self-employment under the NLRA (Abruzzo, 2021, p.4). The reconciliation bill also makes it an unfair labor practice–subject to the new civil monetary penalties–for a firm to inaccurately tell employees that they are independent contractors under the NLRA (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, p. 175-176). This will discourage employers from doing business with independent contractors, for fear of incurring massive fines.

Sharply limiting gig work and freelancing would hurt many workers. Academic economists estimate that rideshare drivers—a large portion of the gig economy—would in the aggregate work two-thirds fewer hours if they had to commit to a fixed schedule as employees (Chen et. al., 2017). Uber has internally estimated legislation reclassifying rideshare drivers as employees would have similar effects (Khosrowshahi, 2020). The draft reconciliation bill advances the Biden administration efforts to restrict independent contracting. This will significantly impact workers who want or need the flexibility to choose their own schedule.

SUBSIDIZING UNION POLITICAL ACTIVITIES

The reconciliation bill also pushes workers to join unions and fund their political campaigns. It includes a $250 above-the-line deduction for union dues. Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (2021, p. 9) estimates this deduction will reduce Federal revenues by $4.2 billion over the next decade. However, the deduction is limited to active union members (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, p. 2322) . Nonmembers who pay union fees cannot claim it.

In non-right-to-work states, unions can require unionized workers to financially support their operations. However, the Supreme Court has held that unions cannot force workers to formally join their organization. Nor can they force workers to fund their ideological activities. Unions can only force workers to pay “agency fees” that cover core representational activities (Communications Workers of America v. Beck, 1988). These agency fees are typically a large portion of full membership dues, but they provide workers some savings. Those savings primarily come from not funding union political activities or lobbying. Approximately 1-in-10 union-represented workers in non-right-to-work states pay agency fees instead of becoming full union members.[11]

The reconciliation bill prohibits agency fee payers from claiming the dues deduction. Only full members–who pay for union political activities–get it. This provision discriminates against unionized workers who oppose union political activities.

This deduction also uses the tax code to indirectly subsidize union political activism. It eliminates most of the financial benefits of becoming an agency fee payer.[12] Enacting it encourages workers to become full union members, and fund union political campaigns. Americans do not get a tax deduction for donating to political campaigns. But the reconciliation bill gives unionized workers a tax deduction for paying dues that specifically fund union political activities.

NONUNION LABOR INELIGIBLE FOR TAX CREDITS

The draft House reconciliation bill creates a $4,500 tax credit for purchasing new electric vehicles–but only electric vehicles manufactured by unionized workers (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, pp. 1869, 1878). Electric vehicles manufactured by nonunion workers do not qualify. This provision makes electric vehicles produced by nonunion labor relatively more expensive. This will mean more jobs at unionized facilities and fewer jobs in nonunion facilities.

This tax subsidy undermines employee freedom. It rewards or penalizes companies and their workers based on how those employees exercise their freedom of association. It reduces the corporate competitiveness–and thus job security–of workers who conclude a union would not benefit them. It also pressures nonunion auto manufacturers to unionize their workers without a secret ballot election, as unionizing makes the vehicles they manufacture eligible for a substantial tax credit.

Retaining federal law’s focus on protecting employee choice–rather than pushing employees to unionize–would serve workers better. Workers can have good reasons for not joining a union. This is especially true of the United Auto Workers (UAW), the principal union representing autoworkers. The past two UAW presidents, along with numerous senior UAW officials, have been imprisoned for corruption (Wayland, 2021). These UAW executives embezzled millions from the union (Jones, 2021). They also took bribes from Fiat Chrysler to make bargaining concessions reducing their members’ compensation (Noble, 2021). The UAW now operates under a government-imposed monitor to combat corruption.

Workers can reasonably conclude that they are better off without such representation. The government should not economically pressure workers to accept representatives they do not want or do not trust.

INCREASING UNION BARGAINING LEVERAGE

The draft House reconciliation bill includes two provisions that increase union bargaining leverage. It prohibits both employer lockouts and hiring “permanent replacements” for striking workers (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, pp. 175-176).

Lockouts are a mirror image of a strike. In a strike, unionized workers withhold their labor to pressure an employer to make concessions. In a lockout, an employer prevents employees from working–or getting paid–to pressure the union to make concessions. This proposal reduces employer leverage and will help unions resist concessions.

The ban on “permanent replacements” operates similarly. The NLRA does not allow employers to fire striking employees, but it does permit companies to hire replacement workers. When the strike ends, the replacement workers keep their jobs, returning strikers fill any vacancies, and the remaining strikers get the right-of-first refusal for future vacancies (National Labor Relations Board, n.d.). This system allows companies to continue to operate during a strike. Very few replacement workers would take positions they were guaranteed to lose when the strike ends. The NLRA allows thus workers to withhold their own labor, but it does not give them the right to prevent a firm from operating altogether.

Unions have long opposed this system.[13] The prospect of being permanently replaced makes unionized workers reluctant to strike. Being able to shut down a company entirely also makes strikes more painful for employers. Prohibiting permanent replacements would substantially increase union bargaining leverage.

In the short-term, prohibiting lockouts and permanent replacements would benefit unions. It would substantially increase their bargaining leverage, enabling them to avoid making concessions they would otherwise grant.

In the long-term, these changes may hasten organized labor’s decline. Union membership has fallen primarily because unionized companies are–on average–less competitive than similar nonunion firms. Over time, less competitive unionized companies fall behind their non-union competitors and lose jobs. This dynamic explains virtually the entire drop in union density since the 1970s (Farber & Western, 2001; Hirsch, 2008).

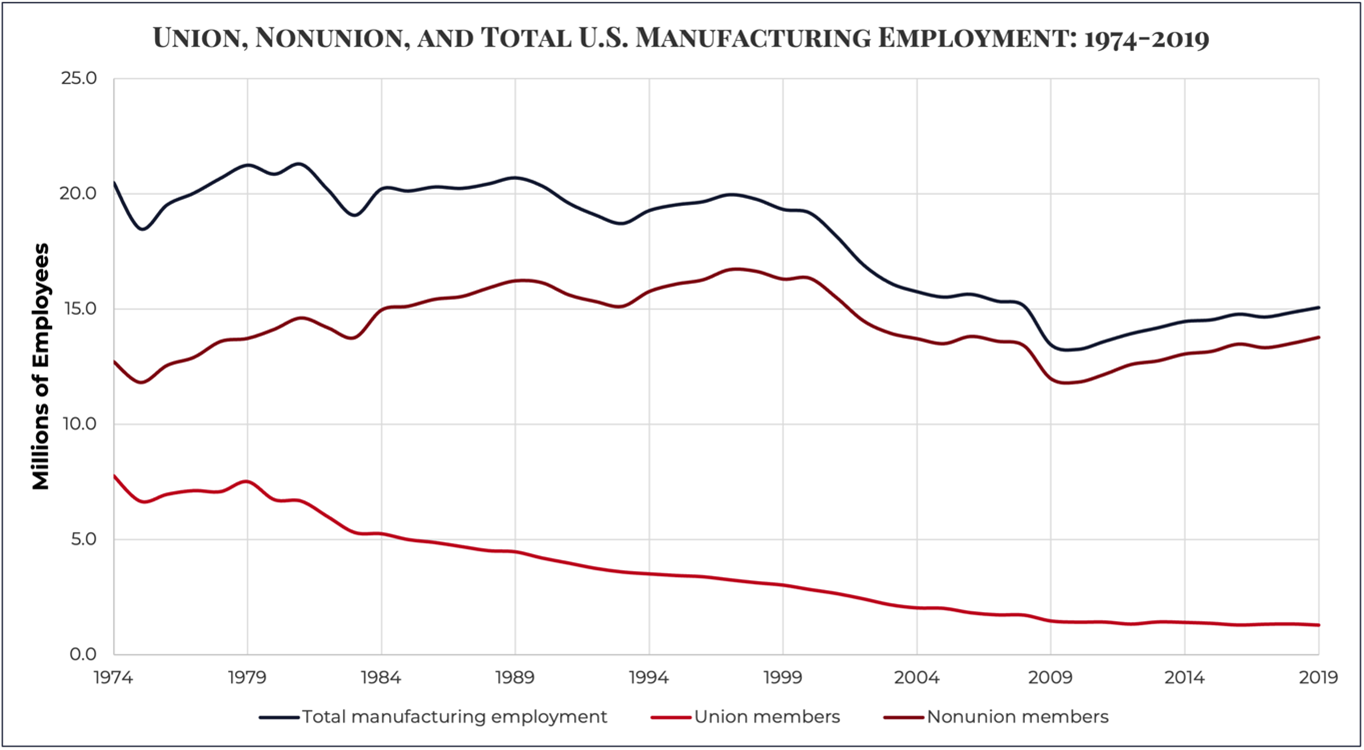

For example, it is widely known that manufacturing employment has dropped since the 1970s. What is less well known is that the entire net decrease in manufacturing employment occurred in unionized firms. In 1974, America had 12.7 million nonunion manufacturing workers and 7.8 million unionized workers–20.5 million manufacturing workers total. By 2021 manufacturing employment fell to 15.1 million workers. That included 13.8 million nonunion workers and just 1.3 million union workers.[14] The five-sixths net decline in unionized employment accounted for the entire drop in manufacturing jobs. Nonunion employment grew slightly. While many nonunion manufacturers went bankrupt during this period, and some unionized manufacturers grew, in the aggregate union job losses drove the entire net decline in manufacturing jobs (Hirsch, 2008).

Source: Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson, “Union Membership and Coverage Database from the Current Population Survey,” Unionstates.com, http://unionstats.com/Private-Sector-workers.htm and from the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics

The labor movement’s fundamental problem is union contracts frequently make firms less competitive. Prohibiting lockouts and permanent replacements could make this problem worse. These provisions will increase union leverage, making it easier for them to stick to their demands at the bargaining table. That seems likely to promote contracts that make unionized firms less competitive in the marketplace.

The ban on permanent replacement workers would also hurt nonunion employees at unionized firms. Currently workers outside the bargaining unit can keep their jobs during a strike–the company can keep operating with replacement workers. If companies facing a strike can only hire difficult-to-recruit temporary replacements, they will often cease operations entirely. This means nonunion workers also lose their jobs and paychecks during the strike.

BAN ON CLASS ACTION ARBITRATION

The reconciliation bill further prevents employers and employees from agreeing to resolve potential class-action lawsuits through arbitration instead of the courts (A bill to provide for reconciliation, 2021, pp. 176-177). Under arbitration agreements, a professional arbitrator resolves legal disputes, and the arbitrator’s decision is binding.

Litigating class-action suits through the courts is time-consuming and expensive. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2015, Table 11, p. 355) reports attorney fees consume over 40 percent of the value of the average class-action settlement (2015, p. 351). Class action lawsuits also rarely provide any benefits to consumers. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2015, p. 351) also found that only 4 percent of consumers receive any relief from the class action lawsuits successfully brought on their behalf.

Arbitration provides a faster and less expensive method for resolving disputes. Trial lawyers oppose arbitration for exactly that reason–it reduces their opportunities to collect attorney fees (Institute for Legal Reform, 2015). Banning employers and employees from arbitrating class action disputes creates job opportunities for trial lawyers, but it would hurt workers. Surveys show that Americans who go through arbitration are highly satisfied with the process (Kaplinsky & Levin, 2015, pp. 3-4). Replacing a timely and efficient mechanism for resolving disputes with one that generates huge attorney fees benefits lawyers, not employees.

SENATE PARLIAMENTARIAN RULING CRUCIAL

It is unclear how many of these proposals will become law. Under Senate rules, reconciliation bills cannot be filibustered. This allows them to be passed by a simple majority on a party-line vote. This procedural benefit comes at a price–Senate rules limit reconciliation bills to measures that directly affect taxes or spending. Policy changes that have “merely incidental” fiscal effects are excluded. The Senate parliamentarian recently ruled that the reconciliation bill cannot include amnesty for illegal immigrants for exactly that reason.

Congressional leaders structured many of these provisions as fines and penalties to maximize their prospects of remaining in the bill. Fines and penalties raise revenue for the government. The Senate has increased civil monetary penalties previously through the reconciliation process. However, there are strong arguments that these reforms would have major policy impacts and only minor budgetary effects. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the civil monetary penalties for ULPs would raise only $4 to $5 million annually in revenues (H. Rep. No. 116-347, 2019, p. 81.). Their primary impact is in changing employer behavior–not raising federal revenues. Nonetheless, until the parliamentarian rules it is not clear which provisions will make it into the final legislation.

CONCLUSION

For almost three-quarters of a century, federal labor law has protected employees’ rights to decide how to negotiate with their employers.[15] Workers have the right to form a union and collectively bargain. They also have the right not to unionize, or to remove an unwanted union. Under the National Labor Relations Act, workers decide. Unions and employers can try to convince employees to unionize or not, but the choice ultimately remains with the employee.

Provisions in the draft House reconciliation bill instead reduce employee freedom. These provisions include measures:

- Preventing employers from discussing the downside of unionizing with employees, making it harder for workers to cast an informed vote;

- Imposing punitive fines for technical violations, giving unions financial leverage to pressure employers into not asking for secret ballot elections and further threatening officers with personal liability;

- Providing tax breaks for workers who pay full union dues, including those that fund union political campaigns;

- Denying electric vehicles manufactured at nonunion facilities eligibility for tax credits; and

- Heavily funding a forthcoming Labor Department initiative to reclassify freelancers and independent contractors as employees.

If they become law, these measures will hurt American workers. Workers benefit when they have the freedom to choose, not when the government makes the choice for them.

Author Biography

James Sherk, is the Director of the Center for American Freedom at the America First Policy Institute, and a senior fellow with the Institute for the American Worker. He previously served as the President’s top labor policy advisor on the White House Domestic Policy Council during the Trump administration.

WORKS CITED

A bill to provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of the Concurrent Resolution on the Budget for Fiscal Year 2022, S. Con. Res. 14., H.R. _____, 117th Cong. (2021). https://docs.house.gov/meetings/BU/BU00/20210925/114090/BILLS-117pih-BuildBackBetterAct.pdf

Abruzzo, J. (2021, Aug 12). Memorandum GC 21-04 to all regional directors, officers-in-charge, and resident officers: Mandatory submissions to advice. National Labor Relations Board, Office of the General Counsel. https://apps.nlrb.gov/link/document.aspx/09031d4583506e0c

Ballotpedia (2020). California Proposition 22, App-Based Drivers as Contractors and Labor Policies Initiative. https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_22,_App-Based_Drivers_as_Contractors_and_Labor_Policies_Initiative_(2020)

Baltimore Sun (1994, July 13). Bill to protect jobs of strikers rejected by Senate. https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1994-07-13-1994194177-story.html

Bannon, P. J. (2015, July 15). DOL issues guidance on independent contractor classification interpreting FLSA broadly to cover most workers as employees. Seyfarth News & Insights. https://www.seyfarth.com/news-insights/dol-issues-guidance-on-independent-contractor-classification-interpreting-flsa-broadly-to-cover-most-workers-as-employees-1.html

Biro, S. (2020, Jan. 24). The Devastating Impact of AB5 on People with Disabilities and Their Families. Gutting the Gig-economy. https://medium.com/@staceybiro/the-devastating-impact-of-ab5-on-people-with-disabilities-and-their-families-fae1b47a76ec

Brudney, J. J. (2004). Neutrality agreements and card check recognition: Prospects for changing paradigms. Iowa Law Review. 90(1), 819-886. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1138&context=faculty_scholarship

California Labor & Workforce Development Agency. (n.d.) ABC test. https://www.labor.ca.gov/employmentstatus/abctest/

Campbell, B. (2020, Nov. 16). Senate split will hamper Biden's labor policy reforms. Law360. https://www.law360.com/articles/1328772/senate-split-will-hamper-biden-s-labor-policy-reforms

Chen, M. K., Chevalier, J. A., Rossi, P.E., Oehlsen, E. (2017, June). The value of flexible work: Evidence from Uber drivers. Working Paper No. 23296, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23296/w23296.pdf

Communication Workers of America. v. Beck, 487 U.S. 735 (1988). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/487/735/

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2015). Arbitration study: Report to Congress, pursuant to Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act § 1028(a). https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201503_cfpb_arbitration-study-report-to-congress-2015.pdf

Crump, J. (1991). The pressure is on: Organizing without the NLRB. Labor Research Review. 1(18), 33-43. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/102578/Issue_18____Article_5.pdf

Dayen, D. (2021, Aug. 2). Anatomy of an anti-union meeting. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/labor/anatomy-of-an-anti-union-meeting/

Deakins, H. L. & Wathen, R. (2009, Apr. 27). Consequences of the Employee Free Choice Act: Union and management perspectives. Heritage Lectures No. 1119. The Heritage Foundation. http://s3.amazonaws.com/thf_media/2009/pdf/hl1119.pdf

Excelsior Underwear, Inc. (1966). 156 NLRB 1236. https://casetext.com/admin-law/excelsior-underwear-inc

Farber, H. S. (1990). The decline of unionization in the United States: What can be learned from recent experience? The Journal of Labor Economics. 8(1), 75-105. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/298245

Farber, H. S. & Western, B. Accounting for the decline of unions in the private sector, 1973-1998. Journal of Labor Research, 22(2), 459-485. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24096266_Accounting_for_the_Decline_of_Unions_in_the_Private_Sector_1973-1998

Freeman, R. & Rodgers, W. (2006). What workers want. ILR Press.

Grimes, K. (2020, Mar. 1). California's AB 5 kills off 40-year Lake Tahoe music festival. The California Globe. https://californiaglobe.com/articles/californias-ab-5-kills-off-40-year-lake-tahoe-music-festival/

Hirsch, B.T. (2008). Sluggish institutions in a dynamic world: Can unions and industrial competition coexist. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 22(1), 153-176. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.22.1.153

Hirsch, B. & Hirsch, J. (2007). The rise and fall of private sector unionism: What next for the NLRA. Florida State University Law Review. 34(4), 1133-1180. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=933493

Hirsch, B. T. & Macpherson, D. A. (2021). Union membership and coverage database from the current population survey. Unionstats.com. http://unionstats.com/

Horton, C. M. (2021, July 22). E-voting in union elections at the NLRB? Labor & Employment Report. Shawe Rosenthal LLP. https://www.laboremploymentreport.com/2021/07/22/e-voting-in-union-elections-at-the-nlrb/

H. Rep. No. 116-347 (2019). https://www.congress.gov/116/crpt/hrpt347/CRPT-116hrpt347.pdf

Independent Contractor Status Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA): Withdrawal, 86 FR 24303 (May 6, 2021). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/05/06/2021-09518/independent-contractor-status-under-the-fair-labor-standards-act-flsa-withdrawal

Institute for Legal Reform (2015, Nov. 2). Dog bites man: New York Times prefers lawyer-controlled class actions over fair arbitration that enables individuals to protect themselves. U.S. Chamber of Commerce. https://instituteforlegalreform.com/dog-bites-man-new-york-times-prefers-lawyer-controlled-class-actions-over-fair-arbitration-that-enables-individuals-to-protect-themselves/

Joint Committee on Taxation, 117th Congress, 1st Session (2021, Sept. 13). Estimated budgetary effects of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to the revenue provisions of subtitles F, G, H, I, and J of the budget reconciliation legislative recommendations relating to infrastructure financing and community development, green energy, social safety net, responsibly funding our priorities, and drug pricing, scheduled for markup by the Committee on Ways and Means on September 14, 2021. JCX 42-41. https://www.jct.gov/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=bedec4a2-9df7-439c-b0fa-549987b35ca5

Jones, S. (2021, Sept. 9). Former UAW presidents Jones and Williams report to prison for embezzling millions in workers' dues money. World Socialist Web Site. https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2021/09/10/corr-s10.html

Joseph, J. (2020, Feb. 25). California youth athletic programs cut back because of freelancer law AB 5. The Epoch Times. https://www.theepochtimes.com/youth-athletic-programs-cut-back-because-of-california-freelancer-law-ab-5_3249945.html

Kaplinsky, A.S. & Levin, M. J. (2015, Aug. 9). CFPB makes consumer arbitration a numbers game - and the numbers overwhelmingly support consumer arbitration. Consumer Financial Services Law Report. 19(7). https://www.consumerfinancemonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2015/09/article_cfslr1907.pdf

Khosrowshahi, D. (2020, Oct. 5). The high cost of making drivers employees. Uber Newsroom. https://www.uber.com/newsroom/economic-impact/

Labor Management Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. § 141 et seq. (1947). https://www.law.cornell.edu/topn/labor_management_relations_act_1947

Magner, B. (2020, Nov. 8). Ten things Biden's NLRB can do to jumpstart industrial democracy. Labor Law Lite. https://brandonmagner.substack.com/p/ten-things-bidens-nlrb-can-do-to

Magner, B. (2021a, Apr. 13). To unionize Amazon, we need to pass the PRO Act. Labor Law Lite. https://brandonmagner.substack.com/p/to-unionize-amazon-we-need-to-pass

Magner, B. (2021b, Mar. 19). The PRO Act would pay for itself. Labor Law Lite. https://brandonmagner.substack.com/p/the-pro-act-would-pay-for-itself

Mek Arden, LLC. (2017, July 25). 365 NLRB 109. https://www.laborrelationsupdate.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2017/07/Mek-Arden-LLC-dba-Arden-Post-Acute-Rehab-365-NLRB-No.-110-July-25-2017.pdf

Morales, I., (2020, Dec. 22). List of personal stories of those harmed by California's AB5 Law. Americans for Tax Reform. https://www.atr.org/ab5

Mueller, E. (2021, Sept. 21). Unions squeeze pro-labor priorities into Democrats’ spending bill. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/21/unions-reconciliation-bill-513423

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 151 - 169 (1935). https://www.nlrb.gov/guidance/key-reference-materials/ley-de-relaciones-obrero-patronales

National Labor Relations Board (n.d). The Right to Strike. https://www.nlrb.gov/strikes

National Labor Relations Board (2000). Your government conducts and election for you—on the job: Information for voters in NLRB elections. https://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/pages/node-184/election.pdf

National Labor Relations Board (2010). Distribution of Unfair Labor Practice Situations Received, by Number of Employees in Establishments, Fiscal Year 2010. https://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/pages/node-149/table18.pdf

National Labor Relations Board, Office of the General Counsel. (2017). An outline of law and procedure in representation cases. https://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/basic-page/node-1727/OutlineofLawandProcedureinRepresentationCases_2017Update.pdf

National Labor Relations Board (2021). NLRB case activity reports. Representation cases: Representation petitions - RC. https://www.nlrb.gov/reports/nlrb-case-activity-reports/representation-cases/intake/representation-petitions-rc

National Law Review (2020, Aug. 28). California AB 5 and the status of independent contractors. Volume X, No. 241. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/california-ab-5-and-status-independent-contractors

Noble, B. (2021, Aug. 17). FCA sentenced for paying more than $3.5M in bribes to UAW leaders. The Detroit News. https://www.detroitnews.com/story/business/autos/chrysler/2021/08/17/fiat-chrysler-sentenced-paying-bribes-uaw-leaders/8166891002/

Penn, B. (2021, Apr. 28). Biden aims to pick Uber critic Weil for return as DOL wage chief. Bloomberg Law. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/daily-labor-report/biden-aims-to-pick-uber-critic-weil-for-return-as-dol-wage-chief-17

Rasmussen Reports (2009, Mar. 16). Just 9% of non-union workers want to join union. https://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/business/jobs_employment/march_2009/just_9_of_non_union_workers_want_to_join_union

Rivera, M., Keyes, J. D., Bosley, J. S., & Capell, J. M. (2020, Sept. 23). California legislature passes sweeping clean-up bill to AB 5. Employment Advisor. Davis Wright Tremaine LLP. https://www.dwt.com/blogs/employment-labor-and-benefits/2020/09/california-ab-2257-independent-contractor-law

Santen, M. (2015, July 16). Independent contractor of employee: DOL's latest guidance on employee status. Ogletree Deakins. https://ogletree.com/insights/independent-contractor-or-employee-dols-latest-guidance-on-employee-status/

Smith, S. & Carron, R. (2010, June 14). NLRB: Is electronic voting on the horizon? ASAP. Littler https://www.littler.com/files/press/pdf/2010_06_Labor_NLRB_ElectronicVoting.pdf

Steiner, T. (2019). Is AB5 closing the curtain on community theater. The Clayton Pioneer. https://pioneerpublishers.com/is-ab5-closing-the-curtain-on-community-theater/?fbclid=IwAR06vv3b4bMSDuFLXxhzbWRSIAEba9zVsHXTodu2OKx_HbJ5nYbOviTneuY

Strengthening America's Middle Class Through the Employee Free Choice Act: U.S. House Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions, Committee on Education and Labor, 110th Cong. (2007) (Testimony of Jennifer Jason). https://edlabor.house.gov/imo/media/doc/020807JenniferJasontestimony.pdf

Swirsky, S. M. & Stutz, L. A. (2017, June 19). NLRB holds supervisor’s text messages to employee were unlawful interrogations – Rejects employer’s argument for “safe harbor." Epstein Becker Green. Management Memo. https://www.managementmemo.com/2017/06/19/nlrb-holds-supervisors-text-messages-to-employee-were-unlawful-interrogations-rejects-employers-argument-for-safe-harbor/

Turl, A. (2009, July 23). Who killed EFCA?Socialist Worker. https://socialistworker.org/2009/07/23/who-killed-efca

Ulin, M. (2021, Sep. 9). Featured in Dems' newest budget draft: A transformative labor law proposal. OnLabor.org. https://onlabor.org/featured-in-dems-newest-budget-draft-a-transformative-labor-law-proposal/

U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). 2010 SUSB annual data tables by establishment industry. Data by enterprise employment size: U.S. & states, totals. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2010/econ/susb/2010-susb-annual.html

U.S. Department of Labor. (2020). Fiscal year 2021 congressional budget justification: Wage and Hour Division. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/general/budget/2021/CBJ-2021-V2-09.pdf

Wayland, M. (2021, June 10). Second UAW president sentenced to 28 months in prison in union corruption probe. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/10/second-uaw-president-sentenced-to-prison-in-union-corruption-probe.html

Weldon, D. G. (2021, June 10). New NLRB rule prohibits solicitation of voters' mail ballots in union elections. Labor Relations. Barnes & Thornburg LLP. https://btlaw.com/en/insights/blogs/labor-relations/2021/new-nlrb-rule-prohibits-solicitation-of-voters-mail-ballots-in-union-elections

[1] 29 U.S.C. § 151.

[2] 29 U.S.C. § 158(a)

[3] 29 U.S.C. § 158(b)

[4] 29 U.S.C. § 159

[5] Under the recognition bar, employees may not vote to remove a newly organized union within 12 months of voting to certify the union (National Labor Relations Board, 2017, pp. 117-119). Under the contract bar, the NLRB will not process a decertification petition while a union and employer have a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) in effect, except for a 30 day window when the CBA nears expiration (National Labor Relations Board, 2017, pp. 85-114). Collective bargaining agreements typically last three years. Thus a newly formed union cannot be removed during the first year of its existence, and if the union negotiates a CBA with the employer during that period, it cannot be removed for a further three years.

[6] In Fiscal Years 2018, 2019, and 2020, unions won 2,200 of 3,042 NLRB conducted certification elections, a win rate of 72 percent (National Labor Relations Board, 2021).

[7] Small businesses receive a disproportionately large portion of ULP complaints relative to their share of the U.S. economy. U.S. Census Bureau (2013) data shows that 51 percent of private sector employees worked in enterprises with fewer than 500 employees in 2010. In that year–the last for which the National Labor Relations Board (2010) published such statistics–employers with fewer than 500 employees received 80 percent of ULP complaints against employers.

[8] The reconciliation provisions tell the NLRB to consider imposing lower penalties for less serious violations. However, it also tells the NLRB to consider imposing higher penalties for ULPs committed during union organizing drives. It is not clear how the NLRB would reconcile these conflicting directives.

[9] The ABC test defines a worker as an employee and not an independent contractor unless all three of the following conditions are met:

- The worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract and in fact;

- The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

- The worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed (California Labor & Workforce Development Agency, n.d).

[10] The Department of Labor (2020, p. 2) reports the Wage and Hour Division spent $242 million in FY 2020. The $405 million the draft reconciliation bill appropriates to supplement WHD operations over FY 2022 and FY 2026 thus represents one-third of the $1.2 billion WHD would spend over five years if Congress held its funding constant.

[11] More precisely, 9.1 percent of private-sector workers that are covered by collective bargaining agreements in states without right-to-work laws are not union members. Source: author’s calculations based on 2020 Current Population Survey compiled by Hirsch and Macphereson (2021). Unions cannot compel agency fee payments from government employees or private sector workers covered by the NLRA in states with right-to-work laws.

[12] For example, consider an employee in a non-right-to-work state who has the choice of paying $500 in union dues or 90 percent of that amount ($450) in agency fees. Although precise numbers differ for each union local, these are typical figures for union dues and the proportion of dues that agency fee payers must pay. If this employee is in the 22 percent tax bracket (e.g. earning between $40,500 and $86,400 for an individual) the $250 tax deduction reduces tax obligations by $55. If that employee joins the union they will pay full dues of $500 and get the deduction–reducing their tax bill by $55–for total costs of $445. If the employee pays agency fees they will forfeit the tax deduction, while reducing their union obligations by $50, for total costs of $450. In this example the employee would be slightly worse off financially becoming an agency fee payer.

[13] The union movement lobbied heavily for legislation prohibiting permanent replacement workers in 1994. That legislation was defeated in the Senate and never became law (Baltimore Sun, 1994).

[14] Author’s calculations using Current Population Survey data compiled by Hirsch & Macpherson (2021) on union membership among private sector manufacturing employees.

[15] The National Labor Relations Act (1935), informally known as the Wagner Act in honor of its main Senate sponsor, protected the right of private sector workers to unionize but did not protect workers from union coercion or provide them a means to remove an unwanted union. The Labor Management Relations Act (1947), also known as the Taft-Hartley Act, amended the National Labor Relations Act to center federal labor law on protecting employees’ freedom to choose. Taft-Hartley reaffirmed employees’ right to collectively bargain in the private sector, while also protecting their right to refrain from collective bargaining. Taft-Hartley made it an unfair labor practice for unions to coerce workers in their selection of a union representative and created decertification elections to remove unwanted unions.