Stumbling into the New Year with More Disappointing Jobs Growth

Key Takeaways:

- After a disappointing month in November, the U.S. economy added even fewer jobs in December and was more than 50 percent below expectations. In total, payrolls only rose by 199,000 jobs as compared to forecasts of 422,000 jobs.

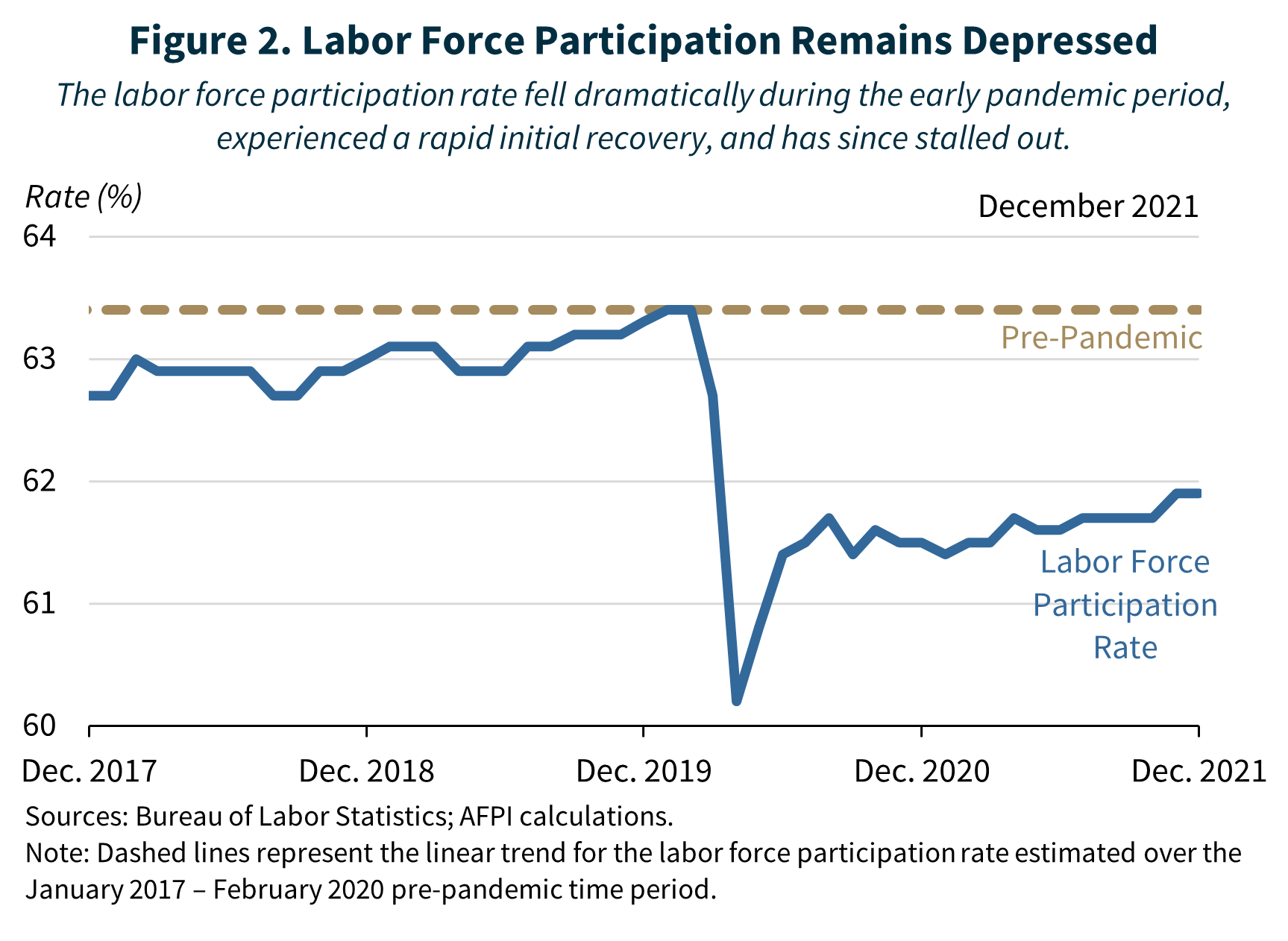

- Although the unemployment rate is back below 4 percent, the labor force participation rate has flatlined, and long-term unemployment remains significantly elevated above pre-pandemic levels.

- The stalled labor market recovery is a startling reversal from the record job growth in the second half of 2020 that was facilitated by pro-worker supply-side policies like the Paycheck Protection Program.

- The fate of the labor market recovery going forward depends in part on whether policy returns to a pro-work consensus or whether the Big Government Socialism Bill institutes permanent work disincentives that enshrine an entitlement-focused universal basic income approach to policy.

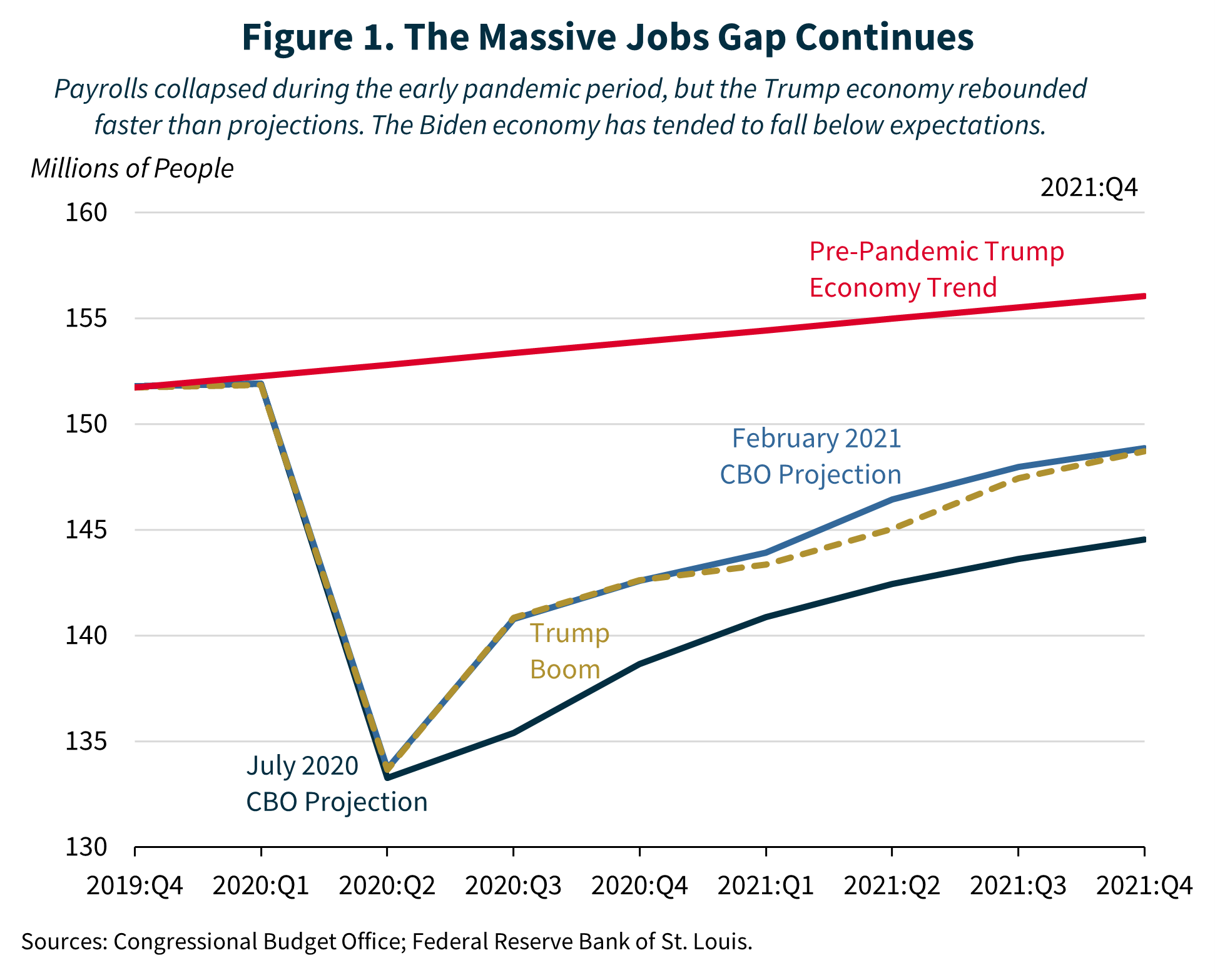

A new year brings new beginnings, but unfortunately for American workers and small businesses, some things stay the same: Another month of lackluster jobs growth. After payrolls fell below expectations in November’s jobs report, data just released from the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveals a further stalling of the economic recovery in December. Forecasters had expected job growth to come in at 422,000, yet the U.S. economy delivered less than half that amount at only 199,000 jobs—even more sluggish than the 249,000 jobs the previous month. With job openings still near record highs, the labor shortage remains very real for small businesses, while families continue to struggle under a generational surge of inflation. In total, payrolls are still 7.7 million jobs short of their pre-pandemic trend.

This limping of the labor market from one month to the next marks a startling reversal from the record job growth in the second half of 2020, when Trump Administration policies were aggressively geared toward accelerating the return to economic normalcy by stabilizing demand and strengthening supply. As evidence for the success of the previous administration’s approach to economic recovery, figure 1 shows that, following the passage of the CARES Act in spring 2020, the ensuing economic boom caused payrolls to vastly exceed CBO projections and set record highs for monthly job growth that placed the recovery on a permanently higher trajectory. The Paycheck Protection Program, in particular, helped lay the foundation for such a robust early recovery by preserving small business finances and strengthening labor market attachment to prevent temporary layoffs from becoming permanent job losses that turn into long-term unemployment, as occurred during the 2007-09 financial recovery and subsequent slow recovery during the Obama-Biden Administration. Unfortunately, the Biden Administration has to date followed a supercharged version of the Obama-Biden Administration playbook by “stimulating” the economy with a raft of policies that discourage work—most notably through enhanced unemployment benefits that paid people more not to work than to work and by stripping the Child Tax Credit of work requirements, which research suggests could drive 1.5 million workers out of the labor force.

If making labor force participation optional is the goal of such policies, they appear to be working. While the headline unemployment rate is back in sub-4 percent territory, recall that the unemployment rate falls not just when unemployed workers get jobs but also when they give up and leave the labor force entirely. According to the latest data, the labor force participation rate has stalled out at 61.9 percent—a full one and a half percentage points below its pre-pandemic value. The employment-to-population ratio also remains depressed at 59.5 percent, below its pre-pandemic value of 61.2 percent. Some have pointed the finger at early retirements rather than bad policies as the reason for the disappearance of millions of workers, but the labor force participation rate for prime-aged workers (those between the ages of 25 and 54) also remains down, at 79 percent versus 80.5 percent before the pandemic. Similarly, the prime-age employment-to-population ratio is 81.9 percent now, whereas it had been 83.1 percent. Put another way, there are 2.5 million fewer prime-aged Americans in the labor force relative to the pre-pandemic trend. In other words, the labor shortage is not a matter of mere population aging. Biden Administration policies have incentivized individuals to sit on the sidelines of the workforce.

Looking forward, the U.S. labor market still has a big hole to recover from. The number of workers who have permanently lost their jobs is still 32 percent higher than before the pandemic, and 31.7 percent of unemployed workers have been jobless for over half a year, compared to only 19.1 percent in February 2020. This long-term unemployment creates the serious risk of a one-way street to lifetime government dependency, which in times past would have raised alarm bells for policy makers across the ideological spectrum. Whether that pro-work consensus remains intact is uncertain, considering that the Build Back Better Bill—known as the Big Government Socialism Bill—would enshrine permanent work disincentives and take an entitlement-focused universal basic income approach to economic policy. The path of future jobs growth depends in part on whether this pro-work consensus survives.