Murderous Cartels, Illicit Drugs, and Human Trafficking: The Threat and Atrocity of America’s Porous Southern Border

TOP LINES

- Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) / Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) represent a clear and present danger to stability in Mexico and Central America and have wide-spread secondary and tertiary impacts on the United States.

- Illegal immigration, which has skyrocketed under the Biden Administration, contributes to the growth and power of these dangerous TCOs/DTOs.

- As Communist China is an integral part of the cartels’ drug supply chain, the current paradigm weakens the U.S. and strengthens this adversary.

- These cartels are violent and dangerous groups that exploit, both financially and sexually, the children, women, and men who seek to enter the United States, and as such anything that supports and empowers the cartels is inhumane.

- In addition to the perils faced by illegal immigrants themselves, permitting illegal immigration has ramifications that threaten the safety, health, and welfare of all Americans.

- Confronting these organized crime networks begins with maintaining border integrity and reducing the demand by American citizens for drugs, particularly addictive narcotics. Additionally, the U.S. should support efforts to thwart cartels’ illicit activities and those materially supporting them, and should seek more accountability from the Mexico, and other foreign governments, in combating transnational criminals.

INTRODUCTION

The data released in Fall of 2021 shows that this year has been the worst on record for illegal border crossings and for American drug overdoses. (CBP, 2021; CDC, 2021a) Unfortunately, these two tragic statistics are not disconnected. A porous border allows for an unfettered stream of drugs and people. The Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) and Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) that operate throughout Mexico, and have affiliates in hundreds of U.S. cities, take advantage of that fact and are at the intersection of these dangerous trends.

Beginning on the first day of the Biden Administration, the measurable and lawful progress made during the previous four years toward securing America’s Southern border was upended in a series of sudden Executive actions and policy changes. These ill-advised decisions include Presidential Proclamation 10142 from January 20, 2021 that terminated progress on the border wall, and the same day the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) ended the partnership with the Mexican government on the Migrant Protection Protocols, otherwise known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy. A policy that required a strong stance from the Trump Administration and the willingness to implement punitive tariffs in the absence of cooperation. A couple of weeks later in February 2021, Secretary of State Blinken suspended and then terminated the Asylum Cooperative Agreements with the Governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, which were known as “Safe Third Country” agreements. (Alper, 2021)

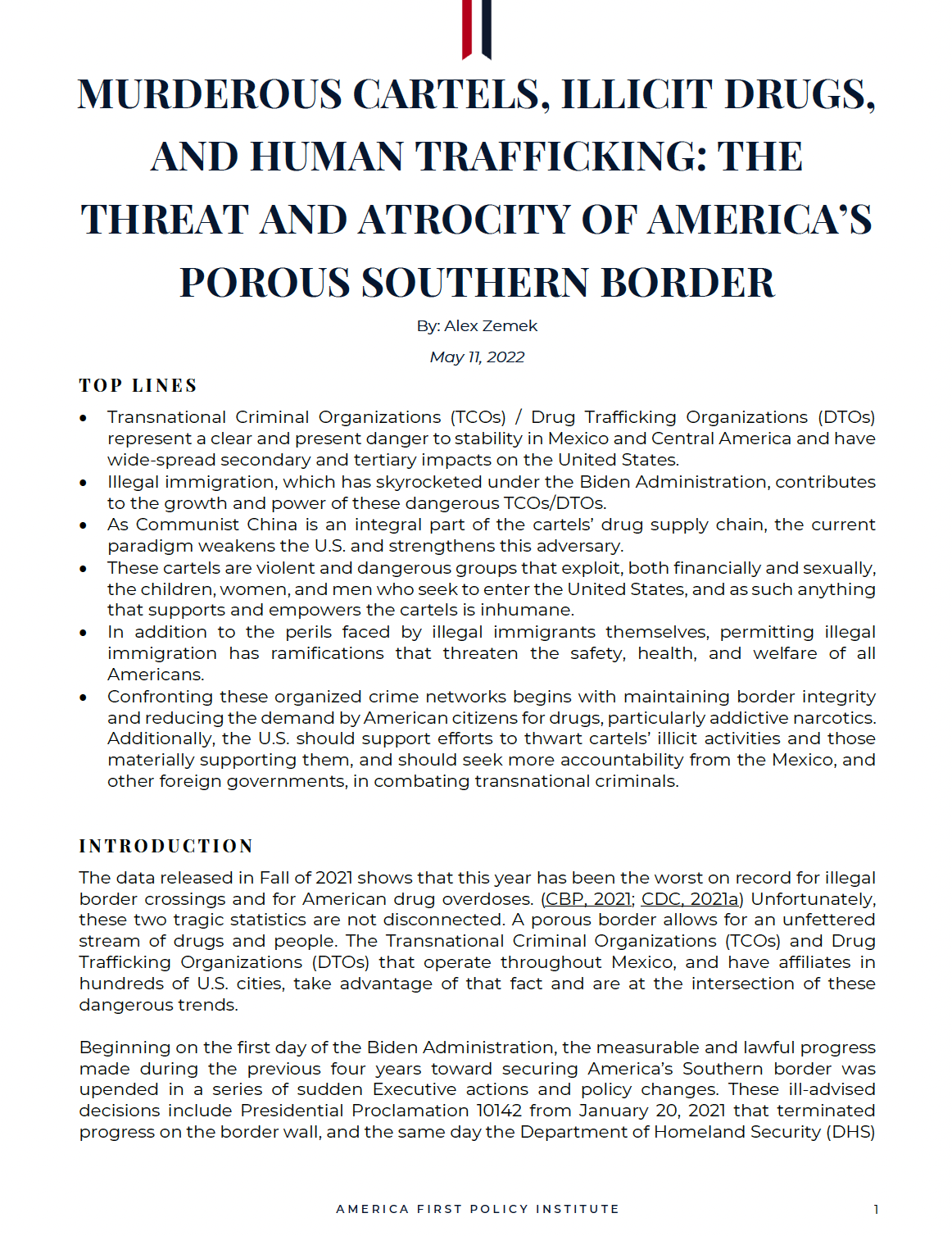

Unsurprisingly, Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 saw the highest number of illegal apprehensions on record at 1.7 million, a 278% increase from FY2020. Given Border Patrol is apprehending over 150,000 illegal immigrants each month, that number will likely exceed 2 million this year. Even more alarming are the estimated 300,000 “got-aways” who have evaded capture since

Figure 1: Example charts reflecting sudden rise in illegal immigrant encounters, particularly during the last year. Graphic Source: Pew Research Center

Abruptly ending these Trump-era policies displayed international weakness and, regardless of the intentions, encouraged masses of people to illegally seek entry to the United States. This was seen in massive caravans of tens of thousands of people starting in Central America and transiting through Mexico. Contrary to the generally innocuous description of illegal immigration, there are stark differences between orderly, secure, legal immigration and chaotic, dangerous, illegal immigration.

As with other unlawful actions, illegal immigration is an enabler and multiplier for more dangerous scenarios. The prospective illegal immigrants pay thousands of dollars to the organized crime networks whose territories they traverse. To the cartels, these people all have price tags. They are expendable and merely represent another means to increase the cartel’s power and profit. The journey the migrants face are often treacherous, as evidenced by the human smuggling tractor-trailer that overturned in Mexico on December 9, 2021 resulting in the deaths of at least 55 children, women, and men. (Suarez, 2021). Even if the immigrants safely arrive to the United States, they often then break other laws while in the country, such as identity theft to obtain documentation for work. (Hegeman, 2008)

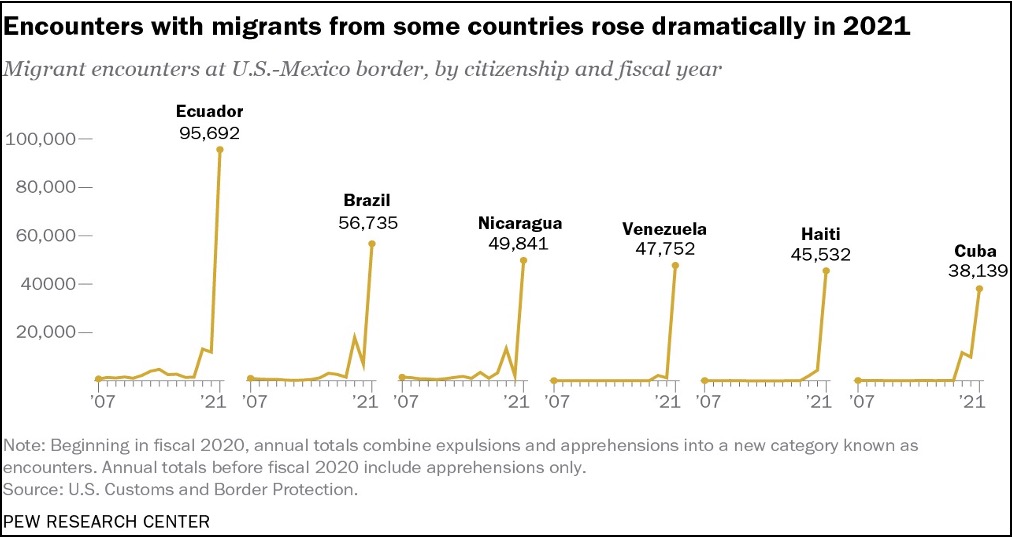

Regarding the health of Americans, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that over 100,000 Americans during the past year died from drug overdoses. (Mann, 2021) Millions of others, who are shackled to drug addiction, fall short of their potential and are a drain on families and society. While adult individuals should be cognizant of the substances they ingest, the nexus of the Mexican cartels, drug trade, and illegal immigration facilitates and perpetuates the American drug epidemic.

Figure 2: Chart shows the rise in drug overdose deaths in the United States, particularly accelerating during the period of time of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador presidency as Mexico has taken a soften stance against the cartels. Graphic Source: Statista

CARTEL OPERATIONS AND NETWORKS

Akin to international terrorist organizations, these Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) / Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) operate outside the customary international norms of nation states and have no regard for the rule of law. In many areas, the cartels in Mexico have supplanted the Mexican government and are a para-state organization. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Mexican TCOs are a great threat to the United States. DEA’s annual National Drug Threat Assessment stated:

“The trafficking and abuse of illicit drugs inflict tremendous harm upon individuals, families, and communities throughout the United States. The violence, intimidation, theft, and financial crimes carried out by TCOs, criminal groups, and violent gangs pose a significant threat to our nation. The criminal activities of these organizations operating in the United States extend well beyond drug trafficking and have a profoundly negative impact on the safety and security of U.S. citizens. Their involvement in alien smuggling, firearms trafficking, and public corruption, coupled with the high levels of violence that result from these criminal endeavors, poses serious homeland security threats and public safety concerns.” (DEA, 2020)

Within Mexico, the power struggle for territorial control between these criminal organizations and their subgroups and splinter organizations is dynamic. The situation in Mexico evolved dramatically in 2006 when former President Felipe Calderon escalated the war against the cartels with significant federal armed forces operations. Though there have been some blows to the cartels, such as the killing of cartel leader Arturo Beltran Leyva and the capturing of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman as well as others on the initial list of 37 most-wanted cartel members published in 2009 by Calderon’s Administration, in many respects the situation has become more complex and more deadly. (Hernandez, 2012) Over the last decade, there has been a shift from a handful of big cartels and some splinter groups to more than 400 gangs operating all over Mexico, with many of those having ties into the United States. This more horizontal network of cartels’ factions and cells provides flexibility and adaptability should a leader become captured or killed. The Mexican police forces at the local, state, and federal level have not been prepared for this development and the proliferation of small gangs and powerful cartels. (Chaparro, 2021)

The less aggressive approach towards the cartels enacted by the subsequent Mexican administrations of Enrique Peña Nieto (December 2012 - November 2018) and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (December 2018 - present) further permitted the cartels and related gangs to engage in deadly turf battles for control of territory across the three main geographic regions of Mexico. (Stewart, 2020) While the territory of control and names of remnant factions change, according to the Mexican government’s Financial Intelligence Unit, presently two the largest, most powerful organized crime groups (delincuencia organizada in Spanish) are the Sinaloa (aka Pacifico) and the Cartel Jalisco New Generation (CJNG). (Express Metropolitano, 2020)

Figure 3: Rendering by the Mexican government's financial intelligence unit displaying the dominant organized crime network in each area. Source: Express Metropolitano

The cartels have the combination of logistic management found in corporate entities and the weapons and firepower found in some militaries. While the drug trade has long been the lifeblood of the cartels, they have diversified to have their tentacles in virtually every sector of the Mexican economy, from avocado farms to nightclubs. (Malone, 2022) Over the past few years, the cartels have further diversified into other crimes such as theft from oil pipelines and cargo shipments, which have siphoned away billions from Mexican government revenue. (CRS, 2020).

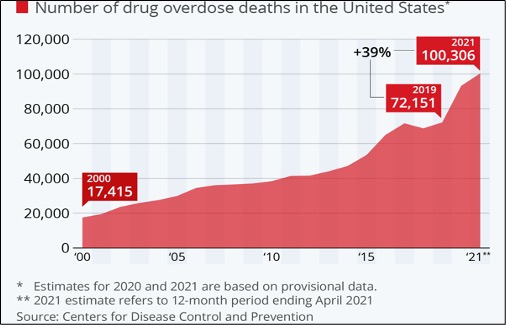

The cartels do not publish revenue filings like legitimate publicly listed companies do with the Securities and Exchange Commission, so there is limited insight into their entire wealth. The drug trade is the bread and butter of the cartels, and while estimates of the Mexican cartels’ annual revenue from the drug trade vary greatly, it likely could be upwards of $64 Billion. (Kolb, 2017) While various drugs including marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine are all produced and transit through the cartels’ hands, synthetic opioids like fentanyl are presently the dominant drug. Based on drug trafficking sentencing statistics, synthetic opioids represented over one-third of all drugs trafficked. (Villa, 2022) These synthetic opioids are easier and cheaper to produce and transport than plant-sourced drugs. China has been the leading supplier of these synthetic opioids and their fentanyl precursor ingredients. As addictive and lethal as previous drugs were, fentanyl is a new breed, potentially 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin. (CRS, 2020) More and more of it is constantly flooding into the U.S., with seizures of the synthetic opioid doubling in 2021. And like the human “got-aways” at the border, much of the fentanyl is not caught or seized when it enters America. To put in perspective the current surge in volume, CBP seized 11,201 pounds (5,080 kg) in FY2021. (Giaritelli, 2021) One kilogram is equivalent to 500,000 lethal doses. Enough fentanyl was caught crossing our border to kill 2,540,000,000 people – or every American seven times over.

Increasingly, drug enforcement agents have found that fentanyl has been laced into other drugs – from cocaine to counterfeit versions of common prescription drugs, like Adderall and Xanax, which has increased the likelihood of overdoses. (DEA, 2021) While Mexican DTOs are working to produce more product domestically, China is the origin of the supplies, including the drug-related manufacturing equipment such as pill presses. (CRS, 2021) A DEA spokesman outlined the process for production:

“Traffickers could typically purchase a kilogram of fentanyl powder for a few thousand dollars from a Chinese supplier, transform it into hundreds of thousands of pills, and sell the counterfeit pills for millions of dollars in profit. If a particular batch has 2 milligrams of fentanyl per pill, approximately 500,000 counterfeit pills can be manufactured from 1 kilogram of pure fentanyl.” (Standaert, 2021).

Typically, the raw chemicals for fentanyl production are shipped in an obscure manner from China for the final product to be constructed by the cartels. For example, the Zheng drug organization aids in drug supplies, money laundering operations, and the criminal enterprise. (Greenwood, 2021; McKay, 2020) The following chart gives a notional summary of the supply chain flow of the fentanyl from China through Mexico to the United States. (Asmann, 2019) The illegal immigrant pipeline across the Southern border of the U.S. represents a key linchpin, as well a diversionary tactic, in the operations and logistics of the cartels and their drug trade.

Figure 4: Overview of a typical route of fentanyl from China through Mexico. Graphic Source: Insightcrime.org

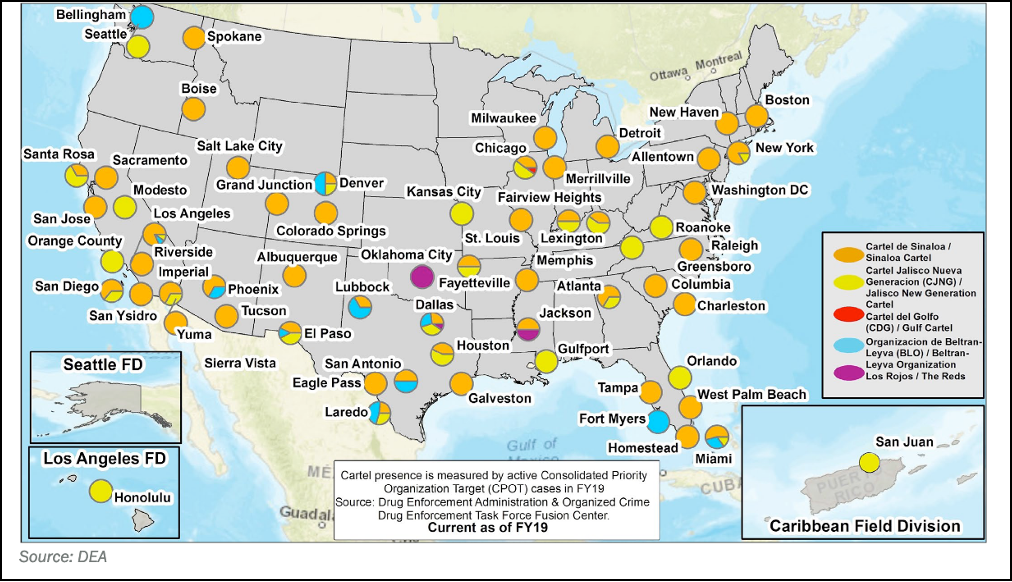

Once the drugs are trafficked across the U.S. border, the American affiliates of these Mexican cartels distribute and peddle their deadly goods. The Mexican cartels reportedly use members of other gangs, such as Mara Salvatrucha (MS 13), for smuggling, transportation, and enforcement purposes. (National Drug Intelligence Center, 2008) The cartels have a polydrug market approach in which the cartels’ distributors sell multiple drugs, permitting flexibility and resiliency to their operations. The Sinaloa Cartel currently has the most prominent presence in the United States, yet multiple cartels are often in a power struggle within the U.S., resulting in further violence and collateral damage. The FBI estimates that there are over 1.4 million gang members in the United States and thousands die each year from gang violence. (FBI, 2022) The cartels have considerable presence in virtually every major U.S. city, as exemplified by the following DEA map. (DEA, 2021) According to the Department of Justice’s National Drug Intelligence Center, the Mexican DTOs have distribution to at least 230 U.S. cities and have a reach directly or via proxy to more than 1,000 cities and towns. (Longmire, 2012).

Figure 5: The cartels and related gangs in the U.S. have a vast presence and reach. Graphic Source: DEA

CHAOTIC, ABUSIVE, AND DEADLY HUMAN TOLL

There is a severe human toll resulting from the triangle of illicit drugs, illegal immigration, and the Mexican cartels. Piles of bodies have been left in the wake of cartel turf battles and gunfights with Mexican government forces. From 2006 through 2018, estimates are that between 125,000 and 150,000 homicides related to organized crime took place in Mexico. This number does not include the 73,000 considered to be missing or disappeared over the past 14 years. (CRS, 2020) Unfortunately, the rate of homicides has even further increased during the past few years and has not abated during the COVID-19 pandemic government restrictions. During the last two years, record numbers of homicides have been reported, with more than 36,000 murders each year. (Associated Press, 2021) The cartels care about power and profits, not about their victims nor the ripple effect of their actions on society. Their killings are not limited to rival cartel members or Mexican soldiers. Whether it was the Langford family massacre in northern Mexico in 2019, German tourists shot in the southern Yucatan Peninsula resort town of Tulum in 2021, or numerous innocent children, all are amongst the dead at the cartels’ hands.

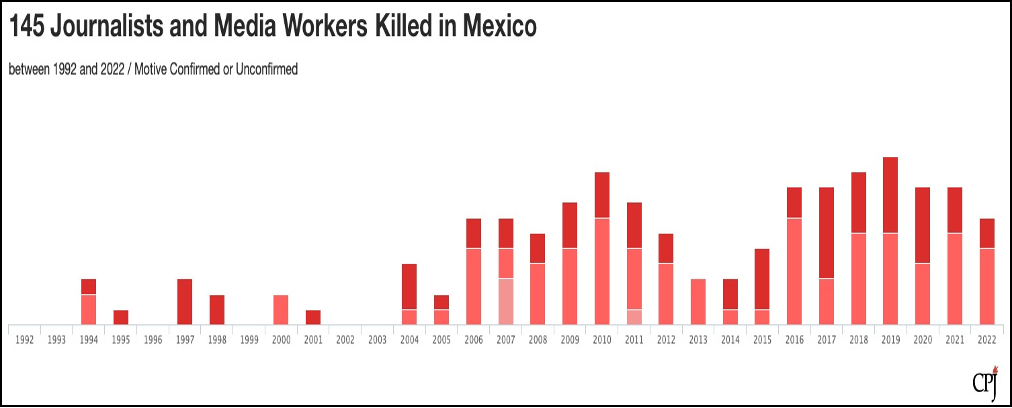

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Mexico has nearly half of the global deaths against journalists and media workers in 2022, and topped the charts in 2021, and 2020; making it the most dangerous country for journalists. Since Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office in December 2018, over 40 journalists and media workers have been killed, many at the hands of the cartels. (CPJ, 2022)

Figure 6: Mexico has recently been considered the most dangerous country in the world for journalists; many of the attacks are pre-meditated due to a journalists coving of the cartels or government corruption. Graphic Source: Committee to Protect Journalists

Beyond the violence and previously mentioned health impacts, there is countless human suffering from the cartels’ operations. The Mexican cartels operate one of the world’s largest human trafficking networks. In a global business estimated to be worth $150 billion a year, Mexico is a key origin, transit, and destination country for human trafficking. (Reuters, 2020) With illegal immigrants and their family members each paying thousands of dollars in smuggling fees, the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol estimates that the cartels can make more than $14,000,000 per day in human trafficking. (Moore, 2021) In addition to those who are consensually smuggled, though they likely may be victimized later, en route to the United States, there are many others who are forced, coerced, or deceived into exploitation. According to the Global Slavery Index, Mexico has approximately 341,000 victims of modern-day slavery - more than any country in the Americas. (Golub, 2019) Women, children, and people with mental and physical disabilities are particularly at risk. They can be forced into prostitution, coerced into forced labor, or used by the cartels to pack drugs and work as lookouts. (Reuters, 2020) These drug organizations take advantage of children in multiple ways. Young adolescents can start working as informants or helping to supply safe houses, and as they mature into their mid-teens, the criminal organizations ask them to conduct murders and kidnappings. The chaos caused by the cartels and the wave after wave of illegal immigrants to the U.S. has overwhelmed the Mexican government and their willingness and ability to address human trafficking. The U.S. State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report assessed that the Government of Mexico fails meet the minimum standards of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000. (U.S. Department of State, 2021)

Knowing that the appearance of a family unit may be less conspicuous for smuggling illicit goods and that if picked up by U.S. border patrol agents the “family” will receive special treatment in the United States, the cartels particularly exploit migrants with young family members or unaccompanied minors. In many instances, children are placed with illegal immigrants or drug runners who are not their parents. Children are often “recycled” – meaning they are used multiple times or discarded after crossing once they fulfilled their use to the cartels. This use of children is so significant that when DHS conducted a one-month pilot program in Texas in 2019 that administered rapid DNA tests of immigrant adults who were suspected of arriving at the southern border with children who weren't theirs, the results were extremely troubling, as approximately 30% of the adults were not related to the children (Giaritelli, 2019). A weak border exacerbates this crisis, as the number of unaccompanied minors encountered by CBP increased by 339% from 2020 to 2021. (CBP, 2020; CBP, 2021)

The Southwest border has become a feeding zone for traffickers, and the Biden Administration has only made it easier for them to gain access to these children. Because effective border security measures were eliminated in the early days of the Biden Administration, smugglers have effectively persuaded migrant children and parents that they had a better chance of being allowed to stay in the U.S. now than under President Trump. The Biden Administration also removed the FBI fingerprint background check requirement for staff and volunteers directly caring for children at the border. (Merchant, 2021) Traffickers could now more easily use false identities to access children at these emergency sites and lure them into trafficking.

The sex trade is another means by which girls and women are exploited by the cartels. According to the Texas Department of Public Safety, children as young as eight years old are sold into prostitution. Many women, up to about age 25, are forced to engage in the sex trade to pay off debts to the human smugglers. (Comins, 2021) Some of the children never reach the United States; it is estimated that out of approximately 150,000 children living on the streets in Mexico, 50 percent are victims of trafficking for sexual purposes. (Golub, 2019)

Even for those who might not be directly impacted by the destruction, carnage, and abuse that stems from the cartels, there are secondary and tertiary impacts. Within Mexico, studies have found that there is broad societal impact. Due to the large amounts of bribery and corruption emanating from the cartels, there is naturally less trust in public officials. (Kim, 2014) Cartels use a portion of their revenue to bribe Mexican judges, police, and politicians. Economists have tried to assess the economic consequences of drug trafficking violence in Mexico, and while the precise impact is hard to measure, some assessments are that the death toll, loss of productivity, and reduced stability negatively impact annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) across Latin America by about 14 percent. (Robles, 2013) The U.S. economy is also damaged by the cartels. Merely looking at the sliver of the financial impact represented by drug overdoses from the narcotics peddled by the cartels and related gangs, the U.S. Commission on Combatting Synthetic Opioid estimates drug overdoses cost the United States $1 trillion annually. (Taylor, 2022)

The cartels seek to make money in any way they can. They are not ideologically driven, unlike Islamists or anarchists. While political, religious, or social change are not the objective of the cartels, they nonetheless employ violence and terror tactics in their quest for territorial control and money. In many respects, this dynamic is equally dangerous since the cartels thrive when there is lawlessness and chaos. The TCOs are free to ally with whomever is most advantageous. The chaotic situation of mass illegal migration is exploited by the cartels in their transiting of drugs, weapons, and people.

The cartels are not the only ones who exploit this chaos; known or suspected terrorists (KSTs) can and have as well. When U.S. Border Patrol agents are spending their time and energy inside facilities tending to the health of children and illegal immigrants, they are not patrolling the border to stop those with more nefarious intentions.

During FY 2021, the Border Patrol pulled more than 40% of its agents from the field to help transport, process, and care for people in custody during the massive waves of caravans. (Giaritelli, 2021) In FY 2021, agents apprehended at the Southwest border a record 1,659,206 illegal immigrants. (Arthur, 2021) More surely snuck across who were not formally apprehended in the middle of night in-between ports of entry. For example, during a May 2021 Senate homeland security committee hearing, it was revealed that DHS estimated in the month of April 2021 alone that more than 40,000 “got-aways” illegally entered America. (Arthur, 2021) The numbers continue to rise.

In August 2021, the Chief of the U.S. Border Patrol revealed that an unprecedented number of KSTs crossed the Southern border during the chaos of the migrant caravans this summer. (Giaritelli, 2021) There continue to be terrorist suspects that take advantage of the porous southern border and the chaos brought on by the cartels and illegal immigrants. For example, in December 2021, it was reported that agents caught a potential terrorist from Saudi Arabia linked to several Yemeni subjects of interest by the border in Arizona. (Dinan, 2021) The illegal transit of terrorists across our border could bring devastatingly deadly consequences for Americans.

During the Biden Administration, more illegal aliens are entering the country, and yet the number of removals of illegal aliens who are already inside our borders, continues to drop. Knowing that there will be able to remain in the U.S. with little consequence of their law breaking, further encourages others to attempt illegal access. During the first fiscal year of the Biden Administration, U.S Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests and deportations for 2021 were over 29,000 less than fiscal year 2020, a 29% drop, and down 50%, from the yearly average during the first three years of the Trump Administration. Regarding deportations, President Biden halted all deportations for the first 100 days of his presidency. According to ICE, deportations have dropped 80% since 2020’s low point, which was during the early stages of restrictions stemming from COVID-19 policies. (Vaughan, 2021) The number of criminal aliens removed (with serious convictions) also dropped by 50%. With hamstrung border security and limited interior enforcement, TCOs and DTOs are able to operate with much greater impunity, and greater wealth as they profit from those who move through their territorial control.

The situation at the border and the resulting national security, economic, and public health ramifications are not expected to improve with current political leadership and their policies. Furthermore, the Biden Administration seems to be adding fuel to the fire. On April 1, 2022, the Biden Administration caused bipartisan outrage by announcing that it would be repealing another lawful and pragmatic Trump Administration policy, called Title 42, which allowed border agents to immediately expel illegal border crossers due to the COVID 19 public health crisis. (Evans, 2022) Once Title 42 is removed, estimates are that 90,000 illegal immigrants per month, who are currently subject to immediate removal under Title 42, will likely be admitted and released into America’s towns and communities. The cartels, traffickers, and smugglers will also advertise this change in policy to encourage even more illegal migration to the United States, furthering their power and criminal enterprise.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The challenges posed by the Mexican TCOs, illegal immigration, and the drug crisis are significant. However, actions can be taken to mitigate the immense damage these are causing.

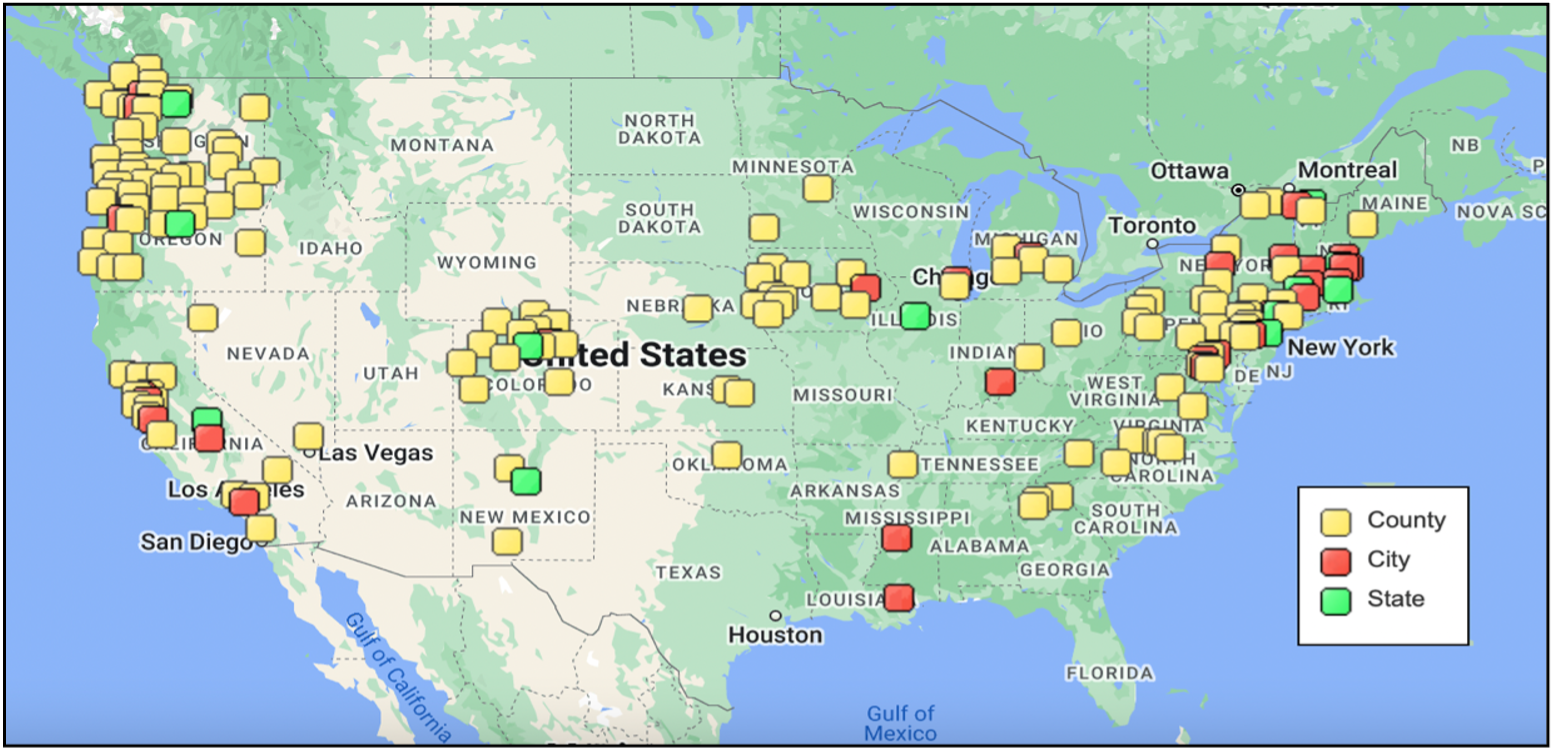

First and foremost, it is critical to re-establish border integrity and reduce pull factors that encourage chaotic and unfettered mass migrations. Resuming the construction of the Southern border wall with Mexico is essential to slowing the cartels movement of people and contraband. Additionally, Federal grants to so-called “sanctuary cities” that do not abide by Federal immigration laws nor cooperate with DHS officials, must be terminated.

Figure 7: There are over 5 sanctuary states, numerous large cities, and scores of countries that do not follow or abide by Federal immigration law or have limitations on their cooperation with immigration officials. Graphic Source: Center for Immigration Studies

The Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), which required asylum seekers to remain in Mexico for their U.S. court hearings, is also a lawful policy that was effective during the Trump Administration. A Federal judge recently ruled the Biden Administration must reinstate this policy that was deemed illegally terminated on January 20, 2021. MPP can help stop the draw of future caravans, which in turn might make a dent into the cartels’ money and the flow of drugs into the United States. Only recently has the Biden Administration begun to follow this court order, but at only a fraction of the rate as before.

Efforts to disrupt the drug supply chain and the demand for drugs can also help to lessen the wealth and power of the cartels. Public awareness campaigns regarding the impact of drugs in financing TCOs and supporting inhumane actions, such as child prostitution and human trafficking, could perhaps dissuade potential future drug consumers. Nearly twenty years ago, after 9-11, the Office of National Drug Control Policy ran similar such ads. (Zabanga Marketing, 2021)

Figure 8: Re-connecting from a public service/messaging standpoint the greater crime and harm that can come from drug use might impact some who are swayed by social issues. Graphic Source: Zabanga Marketing, from Office of National Drug Control Policy

During the Felipe Calderon presidency, the U.S. government’s homeland security, drug enforcement, and intelligence agencies had close and willing partnerships with the Mexican authorities. For the last decade, however, the Mexican government has been winding down many of its anti-cartel operations. The current Obrador Administration has proclaimed its approach to be “Abrazos, no balazos” translated as “Hugs, not bullets.” (Partlow, 2018) However, the cartels are not giving up their guns, and this soft approach, which also saw lessening of cooperation with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, has only resulted in more death. As the impact of the cartels is transnational, the U.S. should use diplomatic pressure on Mexico to pursue a harder stance towards the cartels and illegal immigration. Should Mexico change course, the U.S. could enhance, where possible, support and collaboration with the Mexican government in counter drug operations.

Another way to address the drug supply chain is to limit the supply of fentanyl, methamphetamines, and pill processing equipment from China. Prior to the emergence of COVID-19, President Trump used tariffs and sanctions to build leverage to pressure Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, (CCP), to rein in the flow of fentanyl to America. President Biden has not yet followed suit. The National Security Council admitted that the shipment of fentanyl from China was not part of the topics discussed during the November 2021 virtual summit between Biden and Xi. (Nelson, 2021) While the CCP might not have the will nor the power to rein in every shipment, little can be lost from efforts to increase awareness and pressure on China to stem the flow of fentanyl.

One approach is for the U.S. to apply diplomatic pressure on China to increase its pharmaceutical inspectors and regulators. Reportedly, China has 5,000 pharmaceutical manufacturers, but only a small portion are scrutinized by regulators. For example, in 2017, national Chinese authorities conducted only 15 inspections of manufacturers of narcotics and controlled substances. (Pardo and Kilmer, 2017) For comparison, in 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration conducted 694 inspections of narcotics and controlled substance related drug facilities. (FDA, 2020)

As the cartels operate in many ways like an international terrorist organization, each could be designated by the U.S. Department of State as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) under 8 U.S. Code 1189. While the statute, as presently crafted, has some challenges that could trigger broad secondary and tertiary sanctions, the Secretary of State can quickly and legally designate cartels as an FTO noting that “the terrorist activity or terrorism of the organization threatens the security of the United States national or the national security of the United States.” (U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2014) This designation, if appropriately crafted, can be a powerful tool and lead to broader freezing of assets and blocking financial transactions that could impact the power of the cartels.

The Mexican-based TCOs/DTOs represent a clear and present danger. Addressing the cartels and the closely tied issue of illicit drugs and illegal immigration require significant efforts and focus. Passively downplaying the drug epidemic and excusing away the lawlessness of illegal immigration and ignoring connection of these issues to the cartels is not the right nor humane approach. Admittedly, because cartels have much wealth and power at risk, it is possible that efforts to threaten their current paradigm may be met with increased violence, corruption, and collateral damage. However, even if the challenge to rein in illegal drugs, illegal immigration, and transnational organized crime might be a long and difficult one, it is essential for the safety, health, economic well-being, and security of the United States and its citizenry.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Alex Zemek is a Senior Fellow for AFPI’s Center for Homeland Security and Immigration, and was the Acting Assistant Secretary for Counterterrorism and Threat Prevention at the Department of Homeland Security.

WORKS CITED

“8 U.S. Code 1189: Designation of Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” U.S. Government Publishing Office, accessed at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2014-title8/html/USCODE-2014-title8-chap12-subchapII-partII-sec1189.htm

“2020 Drug Enforcement Administration: National Drug Threat Assessment,” U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, March 2021, DEA-DCT-DIR-008-21, accessed at: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/DIR-008-21%202020%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_WEB.pdf

“2021 Trafficking in Persons Report: Mexico.” U.S. Department of State, Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, accessed at: https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/mexico/

Ainsley, Julia. “18 percent of migrant families leaving Border Patrol custody tested positive for Covid, document says,” NBC News, August 7, 2021, accessed at: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/18-percent-migrant-families-leaving-border-patrol-custody-tested-positive-n1276244

Alper, Alexandra. “Biden administration suspends Trump asylum deals with El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras,” Reuters, February 6, 2021, accessed at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-immigration-centralamerica/biden-administration-suspends-trump-asylum-deals-with-el-salvador-guatemala-honduras-idUSKBN2A702Q

Arthur, Andrews. “All-Time Record for Southwest Border Apprehensions in FY 2021” Center for Immigration Studies, October 22, 2021, accessed at: https://cis.org/Arthur/AllTime-Record-Southwest-Border-Apprehensions-FY-2021

Arthur, Andrews. “More than 40,000 ‘Got-Aways’ at the Border in April,” Center for Immigration Studies, May 21, 2021, accessed at: https://cis.org/Arthur/More-40000-GotAways-Border-April

Asmann, Parker. “US Mailing System Key to Future Fentanyl Trafficking Prevention,” March 6, 2019, accessed at: https://insightcrime.org/news/analysis/us-mailing-system-key-future-fentanyl-trafficking-prevention/

Bier, David. “Let immigrant families pay us - not cartels - to come,” CATO Institute, May 1, 2019, accessed at: https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/let-immigrant-families-pay-us-cartels-come#

Chaparro, Luis. “Mexico’s war on cartels has created 400 new gangs that are taking on the police and the cartels that are left,” Business Insider, October 13, 2021, accessed at: https://www.businessinsider.com/fragmentation-in-mexico-war-on-drugs-created-400-new-gangs-2021-10

“CBP Releases Fiscal Year 2020 Southwest Border Migration and Enforcement Statistics,” DHS/CPB, October 14, 2020, accessed at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-releases-fiscal-year-2020-southwest-border-migration-and

“CBP Releases Operational Fiscal Year 2021 Statistics,” DHS/CBP, January 3, 2022, accessed at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-releases-operational-fiscal-year-2021-statistics

“China Primer: Illicit Fentanyl and China’s Role.” Congressional Research Service, January 29, 2021, accessed at: https://china.usc.edu/sites/default/files/article/attachments/crs-2021-illicit-fentanyl-china%27s-role.pdf

Comins, Joshua. “Migrant women forced into sex trade by traffickers at southern border; Sara Carter reports on ‘Hannity’” Fox News, June 18, 2021, accessed at: https://www.foxnews.com/media/migrant-women-sex-trade-traffickers-southern-border-sara-carter-hannity

“DEA Counterfeit Pills,” DEA, May 2021, accessed at: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-05/Counterfeit%20Pills%20fact%20SHEET-5-13-21-FINAL.pdf

“DEA Threat Assessment.” DEA, March 2021, accessed at: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/DIR-008-21%202020%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment_WEB.pdf

“Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 17, 2021, accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm

“Drug Threat Overview,” National Drug Intelligence Center, April 2008, accessed at: https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs27/27513/drugover.htm

Evans, Zachary. “Moderate Democrats Sound Alarm as Biden Repeals Title 42 amid Border Crisis,” National Review, April 1, 2022, accessed at: https://www.nationalreview.com/news/moderate-democrats-sound-alarm-as-biden-repeals-title-42-amid-border-crisis/

“Fentanyl Flow to the United States,” DEA Intelligence Report, DEA-DCT-DIR-008-20, January 2020, accessed at: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-03/DEA_GOV_DIR-008-20%20Fentanyl%20Flow%20in%20the%20United%20States_0.pdf

“First drugs, then oil, now Mexican cartels turn to human trafficking”. Reuters, April 29, 2020, accessed at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/first-drugs-then-oil-now-mexican-cartels-turn-human-trafficking-n1195551

Firth, Shannon. “Growing Array of Street Drugs Now Laced with Fentanyl,” MedPage Today, July 17, 2018, accessed at: https://www.medpagetoday.com/primarycare/opioids/74071

“FIU reveals drug trafficking map: CJNG and Sinaloa Cartel dominate the country,” Express Metropolitano, September 22, 2020, accessed at: https://www.expressmetropolitano.com.mx/uif-revela-mapa-del-narcotrafico-cjng-y-cartel-de-sinaloa-dominan-el-pais/

Giaritelli, Anna. “DNA tests reveal 30% of suspected fraudulent migrant families were unrelated,” Washington Examiner, May 18, 2019, accessed at: https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/defense-national-security/dna-tests-reveal-30-of-suspected-fraudulent-migrant-families-were-unrelated

Giaritelli, Anna. “Record Fentanyl Seizures at Border Contributed to Soaring Overdose Deaths in the US,” Washington Examiner, November 2, 2021, accessed at: https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/record-fentanyl-seizures-at-border-contributed-to-soaring-overdose-deaths-in-us

Giaritelli, Anna. “Suspected terrorists crossing border 'at a level we have never seen before,' outgoing Border Patrol chief says,” Washington Examiner, August 16, 2021, accessed at: https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/border-patrol-chief-suspected-terrorists-coming-across-southern-border

Golub, Orly. “10 Facts About Human Trafficking In Mexico.” November 2, 2019, accessed at: https://borgenproject.org/10-facts-about-human-trafficking-in-mexico/

Greenwood, Lauren, and Kevin Fashola. “Illicit Fentanyl from China: An Evolving Global Operation,” US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, August 24, 2021, accessed at: https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-08/Illicit_Fentanyl_from_China-An_Evolving_Global_Operation.pdf

Gutierrez, Gabe. “Fentanyl Seizures at the U.S. Southern Border Rise Dramatically,” NBC News, June 29, 2021, accessed at: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/fentanyl-seizures-u-s-southern-border-rise-dramatically-n1272676

Hegeman, Roxanna. “Illegal immigrants turn to identity theft,” NBC News, January 8, 2008, accessed at: https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna22562690

Hernandez, Daniel. “Two-thirds of most-wanted Mexican drug lords in custody, dead,” Los Angeles Times, October 18, 2012, accessed at: https://latimesblogs.latimes.com/world_now/2012/10/mexican-drug-lords.html

“Inspection Observations,” FDA, November 24, 2020, accessed at: https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/inspection-references/inspection-observations

Kolb, Joseph. “Mexican official: Cartels send $64B in drugs into US annually,” FoxNews, February 13, 2017, accessed at: https://www.foxnews.com/us/mexican-official-cartels-send-64b-in-drugs-into-us-annually

Kim, Jacob JiHyong. “Mexican Drug Cartel Influence in Government, Society, and Culture,” UCLA thesis, 2014, accessed at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6tg3z64q

Longmire, Sylvia. “Mexican DTO Influence Extends Deep into United States,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, July 2012, Volume 5, issue 7, accessed at: https://ctc.usma.edu/mexican-dto-influence-extends-deep-into-united-states/

McKay, Hollie. “Chinese 'cartels' quietly operating in Mexico, aiding US drug crisis.” Fox News, November 12, 2020, accessed at: https://www.foxnews.com/world/chinese-cartels-mexico-us-drug-crisis

Malone, Michael. “Mexico cartels blamed for squeezing avocado industry,” University of Miami, February 22, 2022, accessed at: https://news.miami.edu/stories/2022/02/mexico-cartels-blamed-for-squeezing-avocado-industry.html

Mann, Brian. “Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. have topped 100,000 for the first time,” NPR, November 17, 2021, accessed at: https://www.npr.org/2021/11/17/1056484849/drug-overdose-deaths-100000-us?ft=nprml&f=1056484849

Melugin, Bill. “62,000+ Illegal Immigrants Got Past Border Patrol in March,” Fox News, April 1, 2022, accessed at: https://www.foxnews.com/politics/62000-illegal-immigrants-border-patrol-agents-march

Merchant, Nomaan. “US waives FBI check on caregivers at new migrant facilities,” AP News, March 27, 2021, accessed at: https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-health-immigration-child-welfare-coronavirus-pandemic-c4c87f6e76a7fd3ab6e4850ed028c002

“Mexico,” Committee to Protect Journalists, accessed April 7, 2022, accessed at: https://cpj.org/americas/mexico/

“Mexico: Events of 2019,” Human Rights Watch, World Report 2020, accessed at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/mexico#

“Mexico Homicides Remained at High Levels Despite Pandemic,” Associated Press, July 27, 2021, accessed at: https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2021-07-27/mexico-homicides-remained-at-high-levels-despite-pandemic

“Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations,” Congressional Research Service, July 28, 2020, accessed at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R41576

“Encounters with migrants form some countries rose dramatically in 2021,” Pew Research Center, November 8, 2021, accessed at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/09/whats-happening-at-the-u-s-mexico-border-in-7-charts/ft_21-11-01_mexicoborder_5a/

Moore, Mark. “US-Mexico border traffickers earned as much as $14M a day last month,” New York Post, March 22, 2021, accessed at: https://nypost.com/2021/03/22/us-mexico-border-traffickers-earned-as-much-as-14m-a-day-last-month/

Nelson, Steven. “Biden fails to mention top fentanyl exporter China in comments on 100K US drug overdoses,” New York Post, November 17, 2021, accessed at: https://nypost.com/2021/11/17/biden-doesnt-mention-chinese-role-on-100k-drug-overdoses-in-us/

Pardo, Bryce and Beau Kilmer. “China's Ban on Fentanyl Drugs Won't Likely Stem America's Opioid Crisis,” RAND, May 22, 2019, accessed at: https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/05/chinas-ban-on-fentanyl-drugs-wont-likely-stem-americas.html

Partlow, Joshua. “Mexico’s Presidential front runner AMLO doesn’t want to escalate the drug war,” Washington Post, June 30, 2018, accessed at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/mexicos-presidential-front-runner-amlo-doesnt-want-to-escalate-the-drug-war/

Richter, Felix. “U.S. Drug Overdoses Spike Amid the Pandemic,” Statista, November 18, 2021, accessed at: https://www.statista.com/chart/18744/the-number-of-drug-overdose-deaths-in-the-us/

Robles, Gustavo, and Gabriela Calderón, Beatriz Magaloni. “The Economic Consequences of Drug Trafficking Violence in Mexico,” 2013, accessed at: https://cddrl.fsi.stanford.edu/crimelab/publication/economic-consequences-drug-trafficking-violence-mexico

“Sanctuary Policy FAQ,” National Conference of State Legislatures, June 20, 2019, accessed at: https://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/sanctuary-policy-faq635991795.aspx

“Southwest Land Border Encounters,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, December 2021, accessed at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters

Standaert, Michael. “China’s Fentanyl Connection: The Suppliers Fueling America’s Opioid Epidemic.” Post Magazine, February 28, 2021, accessed at: https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/3123109/chinas-fentanyl-connection-suppliers-fuelling

Stewart, Scott. “Tracking Mexico's Cartels in 2020,” Stratfor, February 4, 2020, accessed at: https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/stratfor-mexico-cartel-forecast-2020

Taylor, Chloe. “Drug overdoses are costing the U.S. economy $1 trillion a year, government report estimates,” CNBC, February 8, 2022, accessed at: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/02/08/drug-overdoses-cost-the-us-around-1-trillion-a-year-report-says.html

“USCIS naturalized 834,000 new citizens in FY 2019 – an 11 year high in new oaths of citizenship.” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service, January 16, 2020, accessed at: https://www.uscis.gov/news/alerts/uscis-final-fy-2019-statistics-available

Vaughan, Jessica. “Deportations Plummet Under Biden Enforcement Policies,” Center for Immigration Studies, December 6, 2021, accessed at: https://cis.org/Report/Deportations-Plummet-Under-Biden-Enforcement-Policies

Vaughan, Jessica. “Map: Sanctuary Cities, Counties, and States,” Center for Immigration Studies, March 22, 2021, accessed at: https://cis.org/Map-Sanctuary-Cities-Counties-and-States

Villa, Lauren. “Trafficking Statistics,” American Addition Centers, January 4, 2022, accessed at: https://drugabuse.com/statistics-data/drug-trafficking/

Wen, Clarice Lim Hui. “Mexico’s Drug War: Failure of the “Hugs, Not Bullets” Approach,” Singapore Management University's Premier Economic Research Club, June 14, 2021, accessed at: https://www.smu-seic.com/post/mexico-s-drug-war-failure-of-the-hugs-not-bullets-approach

Zabanga Marketing, “Linking Drug Use with Terrorism,” April 14, 2021, accessed at: https://www.zabanga.us/marketing-communications/linking-drug-use-with-terrorism.html