National Review of Retaining Election Records from the 2020 Election

Key Takeaways

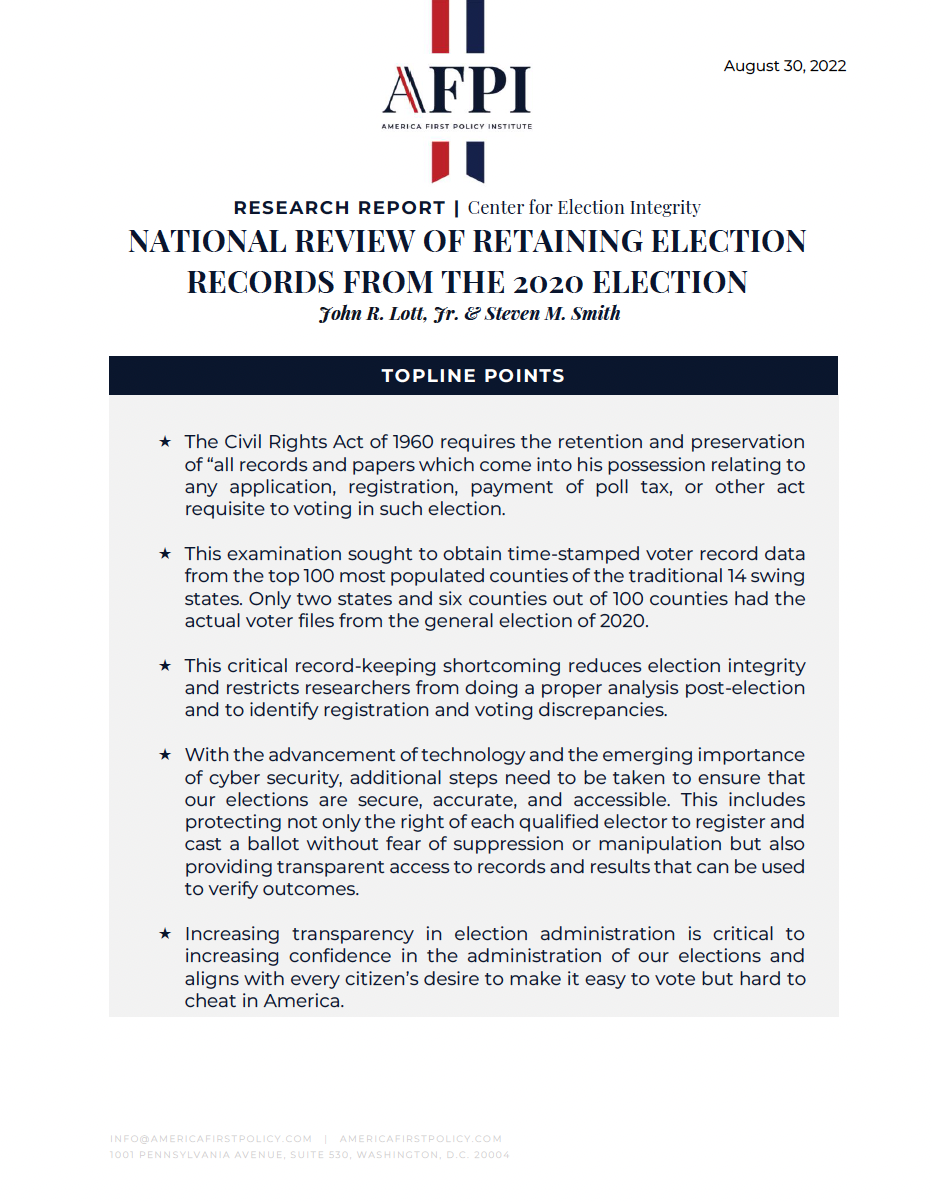

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 requires the retention and preservation of “all records and papers which come into his possession relating to any application, registration, payment of poll tax, or other act requisite to voting in such election.

Increasing transparency in election administration is critical to increasing confidence in the administration of our elections and aligns with every citizen’s desire to make it easy to vote but hard to cheat in America.

With the advancement of technology and the emerging importance of cyber security, additional steps need to be taken to ensure that our elections are secure, accurate, and accessible. This includes protecting not only the right of each qualified elector to register and cast a ballot without fear of suppression or manipulation but also providing transparent access to records and results that can be used to verify outcomes.

This critical record-keeping shortcoming reduces election integrity and restricts researchers from doing a proper analysis post-election and to identify registration and voting discrepancies.

This examination sought to obtain time-stamped voter record data from the top 100 most populated counties of the traditional 14 swing states. Only two states and six counties out of 100 counties had the actual voter files from the general election of 2020.

Who should evaluate the integrity of our Nation’s elections? Is it those in power, leaders of institutions, the media, or the people themselves? Federal law empowers any member of civil society to obtain public records from elections, holding our election officers to a high standard of transparency. But what happens when the data received is inaccurate? Taking advantage of existing legislation, the goal of this project was simple: to see if the number of people who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election equaled the number of ballots cast.

After the last presidential election, there were concerns that ballots may have been counted multiple times (so that there could be more ballots cast than voters who voted) or that ballots were destroyed (so that there could be more voters who voted than ballots cast). By investigating public voter data, the America First Policy Institute (AFPI) believed additional transparency was needed to determine what, if any, discrepancies between these two numbers existed, providing some clarity on the truthfulness of these particular accusations of fraud and malpractice.

To obtain records of voter data from the general election on November 3, 2020, AFPI asked county election officers for their official tabulations of total ballots cast in the election. Most counties have recorders or officials (i.e., County Clerk or Boards of Elections) that oversee the procedures and databases where voters who showed up to vote are recorded (with some different procedures for provisional ballots). If the county officials are not directly tallying the numbers, it is left to precincts and municipal officers. There are usually multiple tiers of data that are reported to the state’s election authority (i.e., Secretary of State) after an election.

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 requires the retention and preservation of “all records and papers which come into his possession relating to any application, registration, payment of poll tax, or other act requisite to voting in such election.” Section 301 states that “Any officer of election or custodian who willfully fails to comply with this section shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.” Section 302 states that “Any person, whether or not an officer of election or custodian, who willfully steals, destroys, conceals, mutilates, or alters any record or paper required by section 301 to be retained and preserved shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned not more than one year, or both.”

After requesting data on both the state and county level from the top 100 most populated counties of the traditional 14 swing states, many officials only responded with current voter records (i.e., as composed at the time of the request, not as of the last election) or a general voter roll to reflect when someone in their district moved or died. The findings of this report confirm that virtually no one (only 6% of county election officials and two Secretary of States of the states and counties reviewed) on the state or county level are correctly retaining the data they are required to preserve regarding voter rolls on the day of each election. As the Civil Rights Act of 1960 stipulates, ballots are part of the records and papers meant to be retained and preserved. In the vast majority of cases, data from the general election was not timestamped nor saved separately. While this may be with the best intentions by election officials to maintain updated voter rolls, it clearly goes against the aforementioned federal law, which mandates election data must be retained and preserved for 22 months after all federal elections. The Civil Rights Act is not outdated or arbitrary; it is a vital safeguard to prevent bad actors from covering up their tracks and to bring transparency to our system, thereby ensuring trust and confidence that everyone’s vote is accounted for in the vote totals.

Even in the six counties that did keep records, there was on average a 2.89% discrepancy between the number of people voting and the number of ballots cast. Below is the list of discrepancies found by county:

- Miami-Dade County, FL: 1.6% (12% of the precincts are missing)

- Orange County, FL: 3.82%

- Cobb County, GA: 8.8% (Secretary of State data 0.68%)

- Woodbury County, IA: 3.06%

- Buncombe County, NC: 0.14%

- Johnston County, NC: 0.07%

In the vast majority of cases, the information necessary to compare the number of ballots cast with the number of people who voted does not exist. In other cases, when that data is available, the numbers don’t match. That is not to say there was incompetence, voter fraud, or stolen elections. It is a question of transparency and accurate records.

Transparency is essential if we are to restore confidence, considering there are roughly 29% of Americans who did not believe the proper winner was declared in either the 2016 or 2020 general elections and that only 59% of Americans feel confident that their votes will be accurately counted. Having these federally (and in some cases state) mandated records retained and timestamped, preferably digitally, would significantly reduce doubt in our democratic process and immediately restore confidence. This should be easily achievable in the digital age, and Americans should expect this sort of retention to happen. It’s not only a civil rights issue but a transparency issue that has eroded confidence in our electoral system.

METHODOLOGY

Public record requests to county officials occurred over several months, beginning in March 2022. This examination sought to obtain time-stamped voter record data from the top 100 most populated counties of the 14 swing states: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Only six of these top county’s election officers responded with their county voter record data of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election without disclaimers (meaning some claim that the data was not exactly retained). For these, we calculated the absolute difference between the total ballot count and the number of voters listed as voting in each precinct as a percentage of the total ballot count.

For subsequent analyses, three main datasets were used: the state dataset we received from the Secretary of State (SoS)/state’s election authority, the county datasets, and the canvasses. The state and county datasets gave us detailed voter data: the names, voter IDs, address, county, precinct, and vote history. This allowed us to calculate registered voters’ ballots cast (RVBC), which we analyzed on a precinct-level, trying to discern how many voters from the state/county data voted in the 2020 general election in each precinct. The canvasses gave us the official tabulations for the precincts from election night or the total ballots cast (TBC), as reported for election results. The analyses we conducted compared these three numbers: TBC (canvass), Secretary of State’s RVBC (state voter file), and county RVBC (county voter file).

FINDINGS

PRECINCT LEVEL DATA AND SECRETARY OF STATE DATA

The county examination grew out of the AFPI’s previous investigation conducted in October 2021, which sought public voter data for 18 states in the 2020 election. AFPI had attempted to obtain and analyze official tabulations on total ballots cast for candidates in the November 3, 2020, election (seven were won by Trump and 11 were won by Biden). The states were: Alaska, Connecticut, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Analysis of these records revealed significant discrepancies between the number of ballots cast and the number of people who voted. Thus, it was necessary to investigate further at the county level, where election data is initially recorded.

AFPI’s original efforts were centered around the Voter Reference Foundation’s (VRF) work to analyze the difference between total ballots cast in various states in the 2020 general election and the total number of voters who cast ballots in that election. Listed below are the discrepancies between the number of ballots cast and voters found from VRF’s data from Secretaries of State, which were obtained through public records requests. For the states marked with “precinct-level data,” this indicates the statistics AFPI obtained from our public records requests to the precinct level, which the VRF did not have at the time of this review.

State | Discrepancy Between the Number of Ballots Cast and the Number of Voters

- Alaska | 3,326

- Connecticut | 37,256

- Colorado | 439

- Florida | 158,319

- Georgia | 52,703 Precinct level data

- Idaho | 11,147

- Michigan | 280,605

- Montana | 1,896

- Minnesota | 48,328

- Nevada | 14,738 Precinct level data

- New Jersey | 56,563

- New Mexico | 3,844

- North Carolina | 21,040

- Ohio | 55,330 Precinct level data

- Pennsylvania | 91,086 Precinct level data

- Virginia | 63,607

- Wisconsin | 14,507

There are some precincts where the total number of ballots cast is greater than the total number of people who actually voted, and other precincts where the total number of voters recorded as voting is greater than the number of votes. There could be one precinct with 100 more votes than voters and another in the same county with 100 more voters than votes. If they were lumped together at the county level, it would look like there were an equal number of voters and votes, but that would hide the problem. Thus, it appears the county-level data underestimates vote discrepancies.

The findings for Pennsylvania revealed that there were three precincts where the number of ballots cast in the November 2020 general election was more than double the number of voters recorded as voting. In those precincts, there was 1,985 more votes than voters recorded as voting.

PROVISIONAL BALLOTS

In Ohio, there was speculation over whether provisional ballots could explain the discrepancies. A provisional ballot is used to record a vote when questions about a given voter's eligibility must be resolved before the vote can count. However, the number of provisional ballots in each precinct was consistently found to be much smaller than these discrepancies. The number of rejected provisional ballots, which would be most relevant to this discrepancy, is even more minute. By comparing the number of rejected provisional ballots to the discrepancies between votes cast and voters listed as voting to see if they were even correlated with each other, a comparison was made in two different ways:

- The number in each category

- The rate in each category as a percent of the total ballots cast

The second effectively adjusts for the size of the county, though both comparisons made it clear that rejected provisional ballots could not explain the discrepancy. As seen below, there is no relationship here.

In Ohio, the data revealing substantial vote discrepancies from the 2012 and 2016 general elections were also broken down at the precinct level.

- In 2020, more votes than voters 38,643, more voters than votes 16,687, total 55,330

- In 2016, more votes than voters 23,464, more voters than votes 20,730, total 44,194

- In 2012, more votes than voters 24,725, more voters than votes 18,125, total 42,850

These findings show an 11,136 increase in the vote discrepancy between 2016 and 2020 (a 25% increase). In 2020, Hamilton County (vote discrepancy of 13,600), Franklin County (7,222), and Cuyahoga County (4,383), accounted for 25,205 of the total discrepancy in Ohio. Moreover, they account for 8,376 of the increase from 2016 to 2020 (75% of the total change in discrepancy).

Data from the Ohio Secretary of State’s office was significantly inconsistent with the county-level data obtained from the public records requests. The findings by the county and precincts for Athens, Cuyahoga, and Williams counties are presented below:

- Athens County Data V. Ohio Secretary of State Data

- For the county total, the Secretary of State’s data showed 37 more ballots cast than voters who voted (26,350–26,313); however, the data from Athens County showed no difference (26,350–26,350).

- The Secretary of State’s data revealed a total discrepancy of 189 between ballots cast and voters who voted. However, the data obtained on the precinct level from Athens County showed a larger discrepancy of 322 between these same two values.

- Cuyahoga County Data V. Ohio Secretary of State Data

- For the county total, the Secretary of State’s data showed 3,191 more ballots cast than voters who voted (631,199–628,008). But the data from Cuyahoga County showed an even larger difference of 19,020 (631,199–612,179).

- Looking at the differences at the precinct level showed a similar pattern. The Secretary of State’s data showed a total discrepancy of 4,391. And the data obtained from Cuyahoga County showed a larger discrepancy of 19,258.

- Williams County Data V. Ohio Secretary of State Data

- For the county total, the Secretary of State’s data showed 14 more ballots cast than voters who voted (18,963–18,949). But the data from Williams County showed a larger difference of 491 (18,963–18,472).

- However, the differences at the precinct level showed virtually the same gap. The Secretary of State’s data showed a total discrepancy of 477. And the data obtained from Williams County showed an even larger discrepancy of 497.

- Given that the data obtained from the county showed a much larger gap when looking at the county total, one would have expected that the discrepancy using the county-obtained data would have also been larger at the precinct level. But that was not the case.

If the observed precinct-level discrepancy in the data obtained from these three counties is representative of what existed in the rest of the state, the total discrepancy for Ohio would be about 230,000, over four times larger than the 55,330 that we obtained using the data from the Secretary of State.

Perplexed by these wild discrepancies, AFPI issued further public records requests to other counties in the states of Texas, Florida, and Ohio, which revealed that many country election officials had been updating and overwriting their voter files from the November 3, 2020, election as voters in their jurisdiction died or moved. In real-time, data was saved over, preventing an accurate comparison with the historical data. This was our first breakthrough and explained why the voter files do not match up because they represent data from different dates, with none of those dates representing the number of people who voted on November 3, 2020. Below is a message from Franklin County, Ohio, claiming their files are fluid or that they do not have a file for the November general election in 2020.

EXAMPLE: Public record request to Franklin County Board of Elections, Ohio.

Similarly, the Nevada Secretary of State’s Office claimed that the gap found from VRF’s review occurred because, "Since (Election Day), numerous voters have cancelled their registrations, passed away, or moved either out of state or to a different county and their record of having voted last November has already been deleted from state records (Nevada Secretary of State, August 2021).” This is a clear admission of not following or being aware of federal law.

As we received more responses from election officials who reported that they only had current data files, it became evident that this might be a systematic issue nationally. In response, AFPI launched a massive campaign of public record requests to county officials in March 2022. This examination sought to obtain time-stamped voter record data from the top 100 most populated counties of the 14 swing states: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin. The goal was twofold, either get accurate time-stamped data on the county level to analyze or get written confirmation to expose that these traditionally important counties were not following the federal law and properly retaining the records from the 2020 general election.

COUNTY-LEVEL DATA

As mentioned above, only six of these top 100 county election officers responded with data of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election without disclaimers (meaning some claim that the data was not exactly retained). Even in the six counties that did keep records, there was on average a 2.89% discrepancy between the number of people voting and the number of ballots cast. Except for Cobb County in Georgia, the data obtained from the county election bureaus showed a smaller discrepancy than that from the Secretary of State’s offices. Excluding Cobb County, the count discrepancy ranged from a low of just 0.07% in Johnston County, North Carolina to 3.82% in Orange County, Florida. Below is the list of discrepancies found by county:

- Miami-Dade County, FL: 1.6% (12% of the precincts are missing)

- Orange County, FL: 3.82%

- Cobb County, GA: 8.8% (Secretary of State data 0.68%)

- Woodbury County, IA: 3.06%

- Buncombe County, NC: 0.14%

- Johnston County, NC: 0.07%

For Miami-Dade, Florida, for just the available precincts, the discrepancy between the number of registered voters who voted and the number of ballots cast is 1.6%. This translates into a difference of 16,617 votes. To give perspective on the size of that gap, in 2018, Senator Rick Scott won Florida’s U.S. Senate seat by 10,033 votes. Nikki Fried became Florida’s Agriculture Commissioner by just 6,753 votes. It is more than half of Governor Ron DeSantis’ victory margin in the governor’s race of 32,463 votes.

Cobb County, Georgia, had an 8.8% discrepancy, amounting to 34,893 votes. That gap, in a county that President Joe Biden carried by 14 percentage points, was three times President Biden’s winning margin in Georgia in 2020. While the data for Buncombe and Johnston Counties in North Carolina only imply discrepancies of 290 and 101 votes, respectively, data from the State Secretary of State’s office raises the possibility that other counties that we were not able to obtain the data from had much larger discrepancies. Even if each of the 100 counties in North Carolina has a discrepancy of 200 votes, that implies a difference for the entire state of 20,000 votes.

In the vast majority of cases, the information necessary to compare the number of ballots cast with the number of people who voted does not exist. In other cases, when that data is available, the numbers don’t match. That is not to say there was incompetence, voter fraud, or stolen elections. It is a question of transparency and accurate records. If Americans cannot see if the number of ballots cast equals the number of voters, they are less likely to trust the election results and may be discouraged from voting in the future.

COUNTY ANALYSIS

Conducting a proper study requires accurate voter files from every level of government. Public records requests were made to the top 100 counties in the county that historically have determined presidential elections, asking for actual, retained data from the 2020 general election. At the county level, these requests were directed to the officer of elections or county. After contacting the country’s most populated counties in historical swing states, responses revealed widespread inconsistency with the laws regarding retaining election files. Going forward, notifying the legislatures, Secretaries of State’s, attorneys general, county election officials, and county attorneys will be crucial to fixing this issue and ensuring the enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1960. Restored trust and transparency in our election system would mark a turning point in our Nation’s history. The following section reports the detailed efforts to obtain the retained data from the 2020 election from the top 100 most populated counties of the 14 “swing states,” which traditionally determine a presidential election.

THE STATE OF ARIZONA

From our analysis of the top counties in Arizona, zero of six counties examined complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Our request for information for voter data in Arizona yielded three counties providing a disclaimer without data: Pima County, Pinal County, and Coconino County. Maricopa and Yavapai County Elections Offices stated they would provide us the data, but their counts would not contain any protected voters (meaning those voters registered without their addresses on file), meaning we could not match it with our numbers for analysis. Apache County redirected us to the County Recorder, where we are presently waiting, as of the date of this publication, for a response confirming that the voter data on file is retained from the November 2020 general election, not just current voters.

Pima County: Disclaimer Stating Only Current Voters

The initial request for information to Pima County occurred on March 8, 2022. We received email correspondence almost immediately on March 9, 2022, that the request would be reviewed. On April 12, 2022, the county responded to our request requesting a fee charge of $331.25 for the voter data with a disclaimer that their data would only represent their current voter list but did not have a voter file from the general election on November 3, 2020.

Pinal County: Disclaimer Stating Only Current Voters

On March 8, 2022, we emailed Pinal County a request for the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We were sent a public records request form, which we signed and returned on April 8, 2022, asking for confirmation that our request would be fulfilled with an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. On April 27, 2022, we received a response from the Community Development Department stating that they were not the department that manages voter information. After following up by phone, it was determined that the lists on file would not contain protected voters. Pinal County requested a fee of $331.25 for the voter data with a disclaimer that their data would only represent their current voter list, not the “frozen in time” data from the November 3, 2020, general election.

Coconino County: Data of The Precincts Where Voters Are Registered But Not Where They Voted

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Coconino County requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Later that same day, the Chief Deputy Recorder informed us that we could purchase a voter list with current voting information. Upon asking for data that would represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election or an updated list, we were offered a list that was run immediately after the election on November 12, 2020. On April 20, they confirmed that this list costing $146.05, would include voters registered in Coconino County at the time the list was generated, as well as their precinct number. However, this data offered would not be consistent with our research objective, which was to obtain a report of the list of voters in each precinct that voted in the 2020 general election.

Maricopa County: Data of Election Participants, excluding Protected Voters

Initial contact with Maricopa County Recorder’s Office was made on March 8, 2022, and a response was received the following day with a public records form from the Custodian of Public Records. On March 14, the county followed up, and on April 5, the public records request was entered into the system. One day later, the County Recorder’s office offered two files of data for purchase, only one of which included voters that participated in the November 3, 2022, general election and both excluded protected voters. On April 7, we confirmed our request for the file and received an invoice on April 8 for $458.76. However, since their counts would not contain any protected voters, we could not match them with our numbers for analysis.

Yavapai County: Data of Election Participants, Excluding Protected Voters

On March 8, 2022, the initial public records request was made to the County Elections Office, followed by an immediate automated response confirming receipt. A day later, the public records request was sent, and on April 12, we were asked to call the County Recorder’s Office and were also informed that the fee for the data of election participants (excluding protected voters) was $230.73. Additionally, we filled out a Voter Registration Records Request Form and Affidavit of Intended Use. However, since their counts would not contain any protected voters, we could not match them with our numbers for analysis.

Apache County: No Response

On March 8, 2022, our initial request to Apache County Elections Office was forwarded to the County Recorder's Office, which did not respond to our inquiry. We followed up with the first office by email on April 7 and were told our follow-up would be sent to the Recorder’s Office. No further details nor data have been obtained at the time of this publication.

THE STATE OF COLORADO

From our analysis of the top counties in Colorado, zero of five counties examined complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. We await a response from two county elections divisions: Arapahoe County and Denver County. They have yet to confirm that their data is retained from the November election, not just the current documented voters list. Adams County Clerk Elections Division provided us a disclaimer without data (they only have a list of current voters). Our search for data in El Paso County (the most populous in the state) led to a phone call with the Department of Elections, who eventually denied our request. Jefferson County confirmed that their data would not represent the historical 2020 voter list. On April 21, 2022, the Colorado Secretary of State’s office informed us of the $50.00 charge for data which would exclude canceled votes, which are not available on any public list. Charges for data ranged from $25.00-$50.00.

El Paso County: Disclaimer without Data

On March 8, 2022, we made our initial public records request to El Paso County Elections. One day later, we received a call stating that election reports would cost $25. We set out to ensure this data would be from the 2020 election rather than a current voter list. On March 14, 2022, we called the county’s Director of Elections to clarify options pertaining to data and which report would best suit our data. From the call, we learned that only the current voter list would be available to us, even though we had previously been told that some reports would capture data right after the election was certified in 2020.

Adams County: Disclaimer Stating Only Current Voters

Our initial correspondence was made to the Adams County Clerk Elections Division on March 8, 2022. We were sent a request form the following day, with the disclaimer that the state voter registration database can only “report the voters as they exist at the time of the report extracted,” which would not reflect the votes cast in the November 3, 2020, general election. Charges were listed from $20.00-$100.00 or more, depending on the type of report requested. A follow-up request was made by our team on March 30, 2022, which has gone unanswered as of the time this analysis was published.

Jefferson County: Data with Disclaimer

Our initial correspondence was made to the Jefferson County Clerk Elections Division on March 8, 2022. Two days later, we were sent two links to access voter and voter history lists in zipped files, and we followed up on March 14, 2022, requesting confirmation that the data from the November 3, 2020, general election was retained in these files. After no response was given, we followed up again on April 26, 2022, and received a response on April 28, stating that the data would “not include any canceled, or deceased voters” and “only have active and inactive statuses not include deceased voters” in other words, they provided the current voter file.

Arapahoe County: Waiting for Response

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Arapahoe County Clerk Election Division requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Two days later, the response stated that certain public lists of registered voters were available online for download at no cost (not including ‘confidential’ or protected voters). After looking at the public lists they provided, we asked to clarify whether this data represented a list of exact voters who voted in the 2020 general election but received no response. A follow-up request was made by our team on April 20, 2022, which has gone unanswered as of the time this analysis was written.

Denver County: Waiting for Response

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Denver County Clerk Election Division requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Two days later, we received a response indicating that elections data could be requested via the website and also referenced the City of Denver website, which stated that the charge would be $40.00. Upon asking for confirmation on whether this data represented a list of exact voters who voted in the 2020 general election rather than a current list, we received no response. A follow-up request was made by our team on April 26, 2022, which has gone unanswered as of the time this analysis was published.

THE STATE OF FLORIDA

From our analysis of the top counties in Florida, three of 10 counties examined complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election, though their data was incomplete. Miami-Dade County and Orange County were able to provide us with lists of people who voted on November 3, 2020, but upon inspecting the data, many precincts were missing, which did not comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1960. For instance, the data from Miami-Dade lacks 12% of the county’s precincts. Three counties, Duval, Hillsborough, and Polk Counties, provided us data of only current voter information. Lee County and Palm Beach County provided disclaimers that the data would be only for current voters. The status of our request to Broward County is still processing, and for Pinellas County, our request for confirmation on the data being not current is still pending. On May 9, 2022, the Florida Secretary of State’s office informed us that they mailed us a CD-ROM data containing the 2020 general election recap file. At the time of this publication, we are trying to locate this package for analysis.

Miami-Dade County: Incomplete Data

Our initial correspondence was made to the Miami-Dade Clerk Elections Division on March 8, 2022, which included the Public Record Request of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. In the response one day later, the Elections Department offered historical data for the 2020 general election via their Record Request via email, informing us of the $20 charge per report. The data was ordered on March 28, 2022, which contained an exact list of voters. Upon further examination of the data, we realized 12% of the precincts were missing, which translates to thousands of votes—a serious issue in trying to discover the discrepancies between voters who voted and ballots cast equal to 1.6% of the vote. After a call with a county elections representative on April 19, 2022, we offered to send files for review and shipped them on April 22, 2022. We sent repeated follow-up messages over email and through the phone but have received no response at the time this report was published.

Orange County: Complete Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Orange County Elections Office requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On April 7, 2022, the Orange County Supervisor of Elections requested a phone conversation, and on April 20, 2022, we provided them with contact information. On April 21, the County Records Management Coordinator informed us that the voter list was completed and accessible, which we received and processed. After analyzing the county election data, AFPI identified a discrepancy that was equal to 3.82% of the vote.

Duval County: Disclaimer with Data

Our initial correspondence was made to Duval County Elections on February 8, 2022, which included the public record request of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On March 21, a link to a data file was provided, with voter data excluding deceased voters and voters who moved out of Duval County and protected voters. Ultimately, we could not match it with our numbers for analysis.

Hillsborough County: Disclaimer with Data

On February 8, 2022, initial contact was made to Hillsborough County containing a public records request for all registered voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On February 17, we received a link to the county’s standard data reports to download files that included multiple categories of data: eligible voters (including inactive voters), all active voters, all Republican voters, all Democrat voters, all NPA/ Minor Party voters, Prior Month New Voters. On March 11, 2022, the county clarified that their available data would not include a report of eligible voters and active voters but not a record of the voters from the November 3 general election. We would not be able to match this with our current numbers for analysis.

Polk County: Disclaimer with Data

On February 8, 2022, we emailed Polk County and received a response three days later with a link to data files. On March 1, 2022, we emailed the Elections Office to confirm that the data represents an exact list of voters from the 2020 general election or an updated list based on voters who had moved, passed away, or otherwise had their data changed. On March 2, we received confirmation that the data was current as of the date the list was generated (February 10, 2022), meaning it would not include information specific to November 3, 2020.

Lee County: Disclaimer without Data

On March 8, 2022, we reached out to Lee County Elections with a public records request and received a response confirming reception later that day. On April 13, 2022, the Supervisor of Elections confirmed that they could provide a file with voter history for the 2020 general election, originating from a live list that would not reflect voters that have been removed from the database since the election. They requested payment of $10.00 by check before emailing the list. Because this list would not reflect November 3, 2020, data, we would not be able to match this with our current numbers for analysis.

Palm Beach County: Disclaimer without Data

The initial contact with Palm Beach County Elections was made on March 8, 2022, requesting their list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. One day later, we received a response that the data request form had been completed and would be processed upon completion of a $20.00 data processing fee invoice. The email response also confirmed that the system is live and that data would only contain active and inactive voters, excluding those that moved, passed away, or are no longer eligible registered voters. Data was not ordered because this list would not reflect November 3, 2020, data and would not match with our current numbers for analysis.

Broward County: Processing

On March 8, 2022, we reached out to Broward County Elections with a public records request asking for a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received a response on March 10, 2022, informing us of the required charges and fees. One day later, we requested confirmation that the data represents an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. After hearing no response and following up with this request on March 22, 2022, we received an email reply on March 29, 2022, stating that the data would reflect a snapshot (as in the time-stamped records) of the 2020 general election period. There has been no communication regarding the status of the request at the time this analysis was published.

Pinellas County: Waiting for Response

Initial contact was made with Pinellas County on March 8, 2022, for a public records request, and on March 10, we were given access to a folder entitled Pinellas County Active Voter Data. On April 7, 2022, a request was sent to confirm the data represents an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election, to which there has been no response at the time this analysis was published.

THE STATE OF GEORGIA

From our analysis of the top counties in Georgia, two of seven counties examined complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Cobb County provided us with an exact list of votes in a timely manner with no charge. Gwinnett County, with the second largest population in the state, denied the request, and we are waiting on a response from Clayton County and DeKalb County. Both Chatham County and Cherokee County redirected us to the Secretary of State’s office, and Fulton County redirected us to a portal. Charges ranged from $52.64 to $65.00. The Georgia Secretary of State’s office provided us with a link to access voter history files, but the page that populates states that the list is “to ensure active electors” and that “specific election requests" should go to counties or municipalities. This Secretary of State dataset was not analyzed as our goals were to get exact voter lists or try to get in writing that they did not have the data being requested.

Cobb County: Completed Request

On April 19, 2022, we reached out to Cobb County Elections with a Public

Records Request asking for a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. One day later, we received a response containing a link with election day data and another link with searchable absentee files. On April 26, we received confirmation that the data emailed to us is reflective of all voters who voted in the November 3, 2020 election, including the precinct where they voted on election day. After analyzing the county election data, AFPI identified a discrepancy that was equal to 8.8% of the vote.

Clayton County: Completed Request

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Clayton County Elections Office. On April 5, 2022, an email from Clayton County Public Records Center informed us that our request was received and that it would be forwarded to the relevant department to determine the volume and costs of fulfilling it. An estimated cost of $52.64 was sent, covering staff time and printing expenses, informing us that the records requested were only available in 492 pages of print. However, analysis was not conducted as there was no response to our request for data in .xlxs, .csv, or .txt format.

Gwinnett County: Denied

Initial contact was made with Gwinnett County on March 8, 2022, for a public records request, and a response was received on March 14, 2022

containing a link to the Open Records Center. On April 9, 2022, we asked for confirmation on whether the data included lists of people who voted in the November 3, 2020 election or if it had been updated since then. The Director of Community Services responded via email the following day, “no, we cannot answer that question.”

Chatham County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Chatham County on March 8, 2022, for a public records request, and after hearing no response, a follow-up was sent on March 30, 2022. On April 7, 2022, we received a response from a paralegal at the Chatham County Attorney’s Office redirecting us to Georgia’s Secretary of State’s office to order or request the documents with voter information.

Cherokee County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Cherokee County in the form of a public record request for the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On March 14, 2022, a representative from the Elections and Voter Registration Office sent us a link to the Secretary of State’s office to obtain the files we requested.

Fulton County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, we reached out to Fulton County Elections with a public

records request. We received a response that same day forwarding our request to the Office of the Fulton County Attorney. An Open Records Request was generated on March 11, 2022, and on March 14, 2022, we received notification that the records request was being processed. On March 24, 2022, the Office of the County Attorney informed us they had not received a response to the request, extending it to April 1, 2022. On April 8, 2022, we were sent a link to records informing us that there were no charges.

DeKalb County: Waiting for Response

Initial contact was made with DeKalb County on March 8, 2022, for a public records request. The Assistant County Attorney responded on March 11, 2022, with a cost estimate of $65.00 for the data requested. On March 14, 2022, we emailed asking for confirmation that the data provided would represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election, not an updated or current list. There has been no response at the time this analysis was published.

THE STATE OF IOWA

From our analysis of the top counties in Iowa, one of seven counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Woodbury County, the sixth largest in the state by population, was the only county to provide us with complete retained voter data. Dallas County provided data representing the current voter list, and Black Hawk County, Johnson County, Linn County, and Scott County informed us that they only retained the current voter list. Polk County, the largest in the state by population, sent an invoice for $135.00 to obtain a file with an exact list of voters. Additionally, we requested the voter list from Iowa’s Secretary of State’s office and were told to fill out a voter list request form and informed there would be a fee.

Woodbury County: Complete

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Woodbury County Elections Office requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received a response on March 31, 2022, asking for clarification on the data requested, to which we responded on April 5, 2022. One day later, a request form was sent to us to begin the data collection process (with the $5.00 fee waived by the Deputy Auditor). On April 6, we asked for clarification that the data provided would represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. Later that day, the county confirmed that it would be. On April 20, 2022, we were sent the complete voter list. After analyzing the county election data, AFPI identified a discrepancy that was equal to 3.06% of the vote.

Polk County: Processing

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Polk County requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On April 20, 2022, we received an invoice from the Polk County Public Records Center for $135.00 for the “initial copy fee … for locating, compiling, researching data, and reproducing public information up to 40,000 records.” We received confirmation that the list was an exact list of voters, but data was not bought due to a lockout. During confirmation requests on the county portal, we became locked out of the online portal and were ultimately not able to buy the data.

Dallas County: Disclaimer with Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Dallas County Elections Office. On April 7, 2022, we received a response informing us of the $10 processing fee and necessary order form to fill out for the records request. We asked for confirmation that the data would represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. Later that day, the County Elections Administrator responded that the data would show voters from the 2020 election, but with current updated data, that meant we would not be able to use it to match our records.

Black Hawk County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact was made with Black Hawk County on March 8, 2022, for a public records request. On April 19, 2022, an additional request was made, which was responded to on April 20, 2022, asking for clarification on the records needed. The county Elections Office informed us that data would be updated and that they did not have “the ability to reference historical data.” Charges were quoted at $33.00 or $63.64, depending on which kind of data was selected.

Johnson County: Disclaimer without Data

On April 5, 2022, initial contact was made with the Johnson County Elections Office requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, General election. The county Elections Technician responded on April 7, 2022, sending us a Voter Registration Record Request Form and informing us of the $41.63 or $38.81 payments for the data, depending on which list of records was selected. They confirmed that the data provided would be updated, not reflecting those that had moved or registered elsewhere since the 2020 general election.

Linn County: Disclaimer without Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Linn County requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Later that day, the Deputy Commissioner of Elections informed us they would work on compiling the report, advising us also to request the data from the Secretary of State’s office. On March 9, 2022, the Election Systems Administrator informed us that they had a voter list from May 26, 2021, for $64.00. They stated that the list is a “snapshot of the data” rather than an exact list since “voters move, pass away or change their information.”

Scott County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact was made with Scott County on March 8, 2022, requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On March 31, 2022, the county Auditor’s Office responded with a request form to fill out, and we noticed that fees started at $10.00 with no possibility for waivers. On April 5, 2022, we asked for confirmation that the data would represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. Three days later, the Auditor informed us that “The Iowa voter data system does not provide a snapshot of historical data” and that the only data they could provide would reflect the current list of registered voters.

THE STATE OF MICHIGAN

From our analysis of the top counties in Michigan, zero of 11 counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Wayne County denied the request, advising more intensive legal action instead. Six counties—Ingham County, Kalamazoo County, Oakland County, Ottawa County, Washtenaw County, and Kent County—provided data with disclaimers that the data on file would not represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. Macomb County provided data with the same disclaimer. Both Genesee County and Saginaw County redirected us to different local offices. At the time this report was written, we are waiting on a response from Livingston County confirming the nature of the data offered. We are additionally waiting on a response from the Secretary of State’s office to provide data that we can verify with county results.

Wayne County: Denied

Initial contact was made with Scott County on March 8, 2022, through a public record request for the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On April 11, 2022, the County Clerk sent a response stating that the request was denied due to incomplete contact information and specificity of information required. Two courses of action were suggested: appealing to the County Executive and involving the circuit court to compel disclosure.

Ingham County: Disclaimer with Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Ingham County requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received an automatic reply that day and another reply from the County Clerk on March 11, 2022, which contained a voter list that did not match the voters from election day because it updates in real time.

Kalamazoo County: Disclaimer with Data

Initial contact was made with Kalamazoo County on March 8, 2022. The Elections Coordinator responded the following day with a voter list that did not reflect data from the 2020 general election but rather current voters. The email stated that historical data did not exist. We were also sent another email on March 10 with instructions on how to submit an official public records request through the county website.

Oakland County: Disclaimer with Data

Initial contact was made with the Oakland County Clerk's Office on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request. On March 11, 2022, the county Elections Division responded with attached files of voters by county, with the disclaimer that “they did not include voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election that have moved or passed away.”

Ottawa County: Disclaimer with Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Ottawa County Clerk. The same day, the Elections Coordinator responded by advising a request through the County’s Public Record Center. This request was submitted on April 5, 2022, and responded to on April 12, 2022, with a link to a Dropbox file containing data of an updated list of voters “who may have moved, passed away, or had their data changed for any other reason.”

Washtenaw County: Disclaimer with Data

On March 8, 2022, we reached out to the County of Washtenaw Elections with a public records request. The following day, a file was sent containing a list of voters “who may have moved, passed away, or had their data changed for any other reason since the November 3, 2020, general election.”

Kent County: Disclaimer with Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Kent County requesting a list of all voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. A follow-up email was sent with the same request on March 30, 2022. On April 7, we filed an official Michigan public records request to the County of Kent Public Record Coordinator. On April 11, 2022, the Elections Director sent an email response with files attached. We received a response on April 19, 2022, containing files of data, and after a follow-up to confirm if the data was an exact list of voters from the November 3, 2020, general election, we were sent an email on April 20 stating that the data was a list of current residents and voters of the county. This email from the Chief Deputy Clerk/Register also stated, “we lack the ability within our Qualified Voter File to run a complete report at the county level of every voter in any given election.”

Macomb County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact was made with Macomb County on March 8, 2022. The following day, the Election Department responded with a form to request data for a charge of $10. We were informed that the database is live and all records would be current.

Genesee County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Genesee County on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request. The response on March 11, 2022, advised that we contact each local clerk in Genesee County, who would be able to provide Qualified Voter File historical data. Due to time restraints, we were unable to reach out to each individual local clerk.

Saginaw County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the County of Saginaw Elections requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Another request was made on March 30, 2022. The following day, we received a message from the County Board Assistant that the request was passed to the Clerk’s Office. On April 5, 2022, we sent a message to the county with the same request for the same data. On April 6, 2022, the response to the public record request was sent, informing us that the request was denied pursuant to the MCL 15.233(1). The public record request was resubmitted on April 26, 2022, but no response has been received at the time of this publication.

Livingston County: Waiting for Response

Initial contact was made with Livingston County on March 8, 2022. Another request was sent on April 7, 2022, requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2022, general election. The county requested clarification on the request made through their portal. We responded to their request for clarification and are still waiting on a response at the date of this publication.

THE STATE OF MINNESOTA

From our analysis of the top counties in Minnesota, zero of eight counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Olmsted County denied the request. Hennepin and Ramsey Counties did not respond after multiple follow-up emails and phone calls. Anoka County, Stearns County, Washington County, Dakota County, and St. Louis County redirected our requests to the Secretary of State’s office. These repeated requests were accompanied by confirmation that obtaining such data would only be allowed to residents of Minnesota for a fee. We were also informed that residency is required when attempting to get this data from the Minnesota Secretary of State’s office. For the sake of time regarding this examination, we concluded our efforts with the state of Minnesota.

Olmsted County: Denied

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Olmsted County requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. A response was sent on March 10, 2022, stating that the State of Minnesota is exempt from the “Requirements of the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 pursuant to 52 U.S.C. § 20503(b)(2).” On April 7, 2022, we sent a follow-up email to the county to clarify the request and ask if historical data was available. The county’s Senior Attorney responded on April 11, 2022, restating that the State was exempt from the National Voter Registration Act regarding public inspection of documents pursuant to 52 U.S.C. § 20503(b)(2)” and stated that “Minnesota Statutes Section 201.091 prohibits access to this information to anyone who is not a registered voter in the State of Minnesota.”

Hennepin County: No Response

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the County of Hennepin Elections requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On March 30, 2022, the same request was made as a follow-up to the unanswered first request email. On April 19, the same request was sent to a different email within the county, with an automated response that delivery failed.

Ramsey County: No Response

Initial contact was made with Ramsey County on March 8, 2022, with no response received. A follow-up request was made on April 19, 2022, with the same information and, has not been answered as of the time of this report.

Anoka County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Anoka County on March 8, 2022, requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We sent a follow-up request on March 30, 2022, and received a response one day later informing us that voter history and registration information is only available to residents of Minnesota and that it would only be a current list. We were redirected to the Secretary of State’s office to request a report for $46 which would only include public voter information.

Stearns County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Stearns County on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We sent a follow-up request on March 30, 2022, and on April 5, 2022, were redirected to the Secretary of State’s office with a link to a list of registered voters made up of current, updated information.

Washington County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the County of Hennepin Elections requesting the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. The following day, the Elections Coordinator responded with a link to contact the Minnesota Secretary of State’s office.

Dakota County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Dakota county on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received a response on March 10, 2022, stating that the information would only be “available to Minnesota registered voters, and for the purposes of elections, political purposes or law enforcement” and that a $46 fee would apply. On March 14, 2022, we asked for clarification on the type of list available and received a response one day later, which confirmed the data would likely reflect changes since the last election but did not state the residency requirement.

St. Louis County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with St. Louis County, requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. A response dated March 10, 2022, informed us that obtaining a registered voter list should be done through the Secretary of State’s office by a legal resident of the state.

THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA: The Secretary of State’s office Does Comply with Federal Law

From our analysis of the top counties in North Carolina, two of 12 counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Buncombe and Johnston counties sent us an exact list of voters in a timely manner with confirmation that they represented historical data. Cabarrus County did not respond to our request, and the Guilford County request is processing. Seven counties redirected the requests to other sources, such as state data, the North Carolina Board of Elections, and a separate public record portal. We are still waiting on a response from Cumberland County, which has yet to confirm if their available data would be current or historical from the November 3, 2020, general election. Our request to the North Carolina Secretary of State Office yielded a statewide voter registration file that omits data only from 10 years prior, meaning that it included accurate voter counts from the November 3, 2020, general election.

From our examination, North Carolina is one of only two states (along with New Hampshire and potentially Florida) that has provided a completed request compliant with federal law on the state level. Because the Secretary of State completed the request and is acting as the custodian of these records for the state, the rest of the counties are, by default, compliant with the public records request, and the following experiences detailed are representative of the county response to the requests sent out.

Buncombe County: Complete

Initial contact was made with Buncombe County on March 8, 2022, requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. The following day, a Communications and Public Engagement official of the county sent lists to spreadsheets of publicly available data on the County’s Open Data Portal. The email response and the links confirmed that the data contained an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 election. After analyzing the county election data, AFPI identified a discrepancy that was equal to 0.14% of the vote.

Johnston County: Complete

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Johnston County Clerk in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received a response on March 10, 2022, with a spreadsheet and asked to clarify by email if it was an exact list of voters who voted. After following up once on April 7, we received confirmation the same day that the spreadsheet was “an exact list” of voters who voted in the general election. After analyzing the county election data, AFPI identified a discrepancy that was equal to 0.07% of the vote.

Cabarrus County: No Response

Initial contact was made with Cabarrus County on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. After hearing no response, a follow-up was conducted on March 30, 2022. A third public records request was made on April 19, 2022, to a different email address in the county elections department. At the time of this report, the request has not been answered.

Guilford County: Processing

Initial contact was made with Guilford County on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. A follow-up email was sent on March 30, 2022, and we received a response the following day, advising that the request had been received and that the county was “working to determine if there are any responsive documents.” At the time of this report, the request has not been fulfilled.

New Hanover County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, a public records request was made to the County of New Hanover Elections for a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. The April 20, 2022, response provided us with a link to Statewide Voter History and a Statewide Voter Registration File, telling us to contact the North Carolina State Board of Elections with further questions.

Durham County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Durham County on March 8, 2022, but the email was marked as undeliverable. On April 5, 2022, we sent another request and received a notification six days later that our request had been fulfilled, directing us to the State Board of Elections Voter Lookup tool and stating that there was no charge.

Forsyth County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, a public records request was made to the Forsyth County Clerk for a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. There was a follow-up on April 19, 2022. The response the following day advised us to contact the North Carolina State Board of Elections.

Gaston County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Gaston County on March 8, 2022, with a response received a day later containing a link to the North Carolina State Board of Elections website of voter data. The state website clearly differentiates current from historical voter data, with files dating back to 2000.

Mecklenburg County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Mecklenburg County Clerk in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. The same day, we received a response with the link to a zip file of the county voter data, to which we responded to confirm whether it was current or historical data. On March 20, 2022, the county confirmed that historical data could only be found on the state site.

Union County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with the Union County Clerk

in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. A follow-up email was sent on March 30, 2022, with an identical request. The response advised us to contact the North Carolina State Board of Elections.

Wake County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Wake County on March 8, 2022. We received a response on March 30, 2022, informing us that a member of their staff would assign the request to a team member for assistance. On March 31, 2022, we received notification that the public records request was opened, under review, and closed. The stated closure reason was that the records requested were available to the public on the North Carolina State Website. Two specific data sources were linked: a statewide voter history file and a statewide voter registration file.

Cumberland County: Waiting for Response

On March 8, 2022, an initial request was made to Cumberland County for the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. On March 9, 2022, a drop box file was shared, but the data was clarified to be a copy of the North Carolina State Voter Database, which would not have helped with our intended analysis.

THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE: Secretary of State’s office Does Comply with Federal Law

From our analysis of the top counties in New Hampshire, zero of four counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960 and retained the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. The County of Strafford denied our request, instead advising us to contact the Secretary of State or the cities and towns responsible for retaining data. We did not receive a response from the County of Merrimack. Rockingham and Hillsborough County redirected us to contact smaller municipalities in the state for relevant information.

After our extensive outreach on the local level and initial requests to the Secretary of State’s office, we had an in-person meeting with New Hampshire Secretary of State David Scanlan and Deputy Secretary Erin Hennessey on June 30, 2022. Secretary Scanlan reviewed our findings and public records requests, walked us through the state election procedures, and was incredibly transparent regarding the process that each municipality takes to secure the chain of custody. He was cooperative with our requests, sharing their voter files from election day in hard copy form. New Hampshire’s collection procedures are dated and time intensive, requiring about a month to review hard copies that make their way into the State Archives in Concord. Though the data is not easily accessible for researchers to review quickly (we were told the electronic files were too large to send over email), New Hampshire, from our understanding, does, in fact, comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, but if we wanted to review the data, they could only supply PDF’s and not digital versions.

Strafford County: Denied

Initial contact was made with the County of Strafford on March 8, 2022, in the form of a public records request for the voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. A follow-up was conducted on March 30, 2022, with a response received the following day by the Town Clerk. We were informed that the inquiry would be shared with the Secretary of State. On April 11, 2022, the County Commissioners Office sent a response advising us to either contact the Secretary of State or the cities and towns responsible for retaining data.

Merrimack County: No Response

On March 8, 2022, an initial request was made to Merrimack County for the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Another request was filed on April 5, 2022, and a response had not been received at the time of this report .

Rockingham County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Rockingham County on March 8, 2022. On April 7, 2022, another request was made containing the same information. After speaking with Rockingham County representatives by phone, we were advised to contact every city or town in the county for the list of voters.

Hillsborough County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Hillsborough County Elections. A follow-up message was sent on March 30, 2022. Ultimately, we were advised to submit a form to the county for the requested data. Due to time restraints, we decided to meet with the Secretary of State and were able to receive the data from the state.

THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO

From our analysis of the top counties in New Mexico, zero of four counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Bernalillo County and Santa Fe County answered our requests with disclaimers that their data only represented current voters. Dona Ana County redirected us to a different form with the state, and Sandoval County advised us to contact the Secretary of State’s office.

Bernalillo County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact was made with Bernalillo County on March 8, 2022, for the list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. Later that day, we were informed that the Bureau of Elections had received our inquiry. After hearing no response for over one month, we sent a follow-up email on April 20, 2022. Later that day, the county sent us a form to complete to make an official request for voter data. The email also stated that the “Bernalillo County Clerk’s office charges $4 per 1000 (one thousand) records.” and “that there are nearly 450,000 registered voters within the county.” However, the data available was confirmed to be “live and not historical.”

Santa Fe County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact was made with Santa Fe County on March 8, 2022, but the email was marked as undeliverable. On April 5, 2022, we sent another request and received a response the following day, containing a request form and stating that “Voter Registration information is subject to the Election Code not public record in New Mexico.” On April 7, 2022, we asked to clarify whether the voter data available was live or historical, and the response confirmed it was current.

Dona Ana County: Redirect

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Dona Ana County Elections. After sending a follow-up, the county responded on April 11, 2022, with a Public Service Request form, notifying us that charges of $25 would apply for data processing and $3 for credit card usage. On April 14, 2022, we asked for confirmation that the data was historical, not current, and five days later, we received a response telling us to fill out an updated form before they could determine if the requested data was available. The updated form was a Voter Data Request Form from the State of New Mexico, not the county. The minimum charge stated on the form was $15.

Sandoval County: Redirect

Initial contact was made with Sandoval County on March 8, 2022, requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. After hearing nothing, a follow-up request was sent on March 30, 2022. The county attorney responded on April 4, 2022, informing us that the data would be in the Secretary of State Database, not held by the county. Our public records request was forwarded to the state. On April 7, 2022, we reached out asking for any updates on the request, which remained unanswered at the time of this report.

THE STATE OF NEVADA

From our analysis of the top counties in Nevada, zero of two counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. Both Clark County and Washoe County informed us that the data available was current rather than an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. After requesting the data from the Nevada Secretary of State’s office, we were sent a link on June 6, 2022, to a file of the data requested, with notice that participants in the Confidential Address Program have been removed, which would make the data insufficient for our analysis.

Clark County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact with Clark County Elections was made on March 8, 2022, requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. The request was forwarded that day to other county officials. An election department administrator responded, stating that the data might take a while to compile and that the voter registration would “have changed from the 2020 election and updates/removals of records may have occurred between November of 2020 to present.” They also informed us of a $ .01 fee per record not to exceed $130.00 unless the request needed additional information processed.

Washoe County: Disclaimer without Data

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with Washoe County Elections

requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. That same day, we received a response informing us that the request would be seen by the Registrar of Voters. On March 14, 2022, the Assistant Registrar of Voters informed us charges for this data were $3,403.01 (0.01 per name). On March 15, 2022, we asked for clarification that the data provided would represent an exact list of voters who voted in the 2020 general election. It was confirmed to be a list of voters at a certain point in time “that may or may not have vote credit for the 2020 general election. The confirmation email also stated, “As we get further away from a specific point in time the data does change. This list only represents individual voters that received vote credit.”

THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

From our analysis of the top counties in Pennsylvania, one of eight counties complied with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, retaining the voter data from the November 3, 2020, general election. After directing our request to the Pennsylvania Secretary of State’s office, we were informed that the Pennsylvania full voter export site contained historical data from specific points in time of each year. In certain cases, we were told that only residents could obtain voter data, and the Pennsylvania state portal requested the submission of ID numbers. We received a denial from both Allegheny County, Lancaster County, and York County, requiring requests to be made by local registered voters. Bucks County and Chester County confirmed that their data only included current voters, and Montgomery County has not responded to multiple requests for data, including follow-ups. Philadelphia County redirected us to a state form for requesting data, and no response has yet been received from Delaware County.

Allegheny County: Denied

Initial contact was made with Allegheny County on March 8, 2022. On March 17, 2022, the Director of the county Open Records Officer responded, informing us that election records” are public information access to which is governed by the Pennsylvania Election Code,” rather than RKTL. A form titled “Affirmation Pursuant to Request for Election Information,” was attached to help us obtain records. However, successful completion of this form required PA identification (driver’s license, photo card, employee card, non-photo ID).

York County: Denied

On March 8, 2022, initial contact was made with York County, requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received a response on March 15, 2022, from the York County Board of Commissioners, denying the request under state law. The letter detailed that “Elections and Voter Registration Department are not generally accessible under the RTKL, as those documents are governed by the Election Code.” Data governed by the election code is only available to local registered voters. Additionally, the county received our separate Right to Know Request on May 27, 2022. On June 6, 2022, we received a denial from the county solicitor’s office stating that the county would not be legally obligated to reply to duplicate requests.

Lancaster County: Denied

Initial contact was made with the Lancaster County Court of Common Pleas on March 8, 2022. Two days later, we received a response denying the request “because the information/records requested are not financial records and/or are not in possession of the courts as defined by Pa.R.J.A. 509(a).” A right-to-know request was also made to Lancaster County, and we received a response on May 5, 2022. This request was also denied in accordance with RTKL, stating that “the record is exempt from disclosure under any other Federal or State law, regulation or judicial order.” According to the county, the data could only be obtained by a local resident and would only be available in a non-electronic format.

Bucks County: Disclaimer without Data

Initial contact was made with Bucks County on March 8, 2022, requesting a list of voters who voted in the November 3, 2020, general election. We received a response on March 10, 2022, from the county Voter Registration Office Supervisor providing us with a link to request data, in addition to a suggestion to contact the Secretary of State’s office. The response also stated that requestors must be registered Pennsylvania voters and that charges would range from $20.00-$23.50.

Additionally, the email clarified that all exported data included voter history for current voters.

Chester County: Disclaimer without Data