Gender Transition Medications and Surgeries for Children in the U.S.

Key Takeaways

The U.S. currently has the most permissive laws surrounding transgender treatments for children compared to peer Western and Northern European nations.

Only 12–27% of children with gender dysphoria—a condition where one’s perceived gender identity differs from their biological sex—carry it into adulthood, yet many children in the U.S. are still eligible for irreversible therapies and surgeries.

Many puberty blockers given to children are prescribed for off-label (unapproved) use and can have dangerous side effects, including lowered bone density, stunted growth, and permanent infertility. There is limited research on the long-term effects of transgender interventions on children and little evidence of mental health benefits.

Policymakers should adopt policies to protect children from potentially harmful and irreversible sex reassignment surgeries and medications.

Executive Summary:

Rates of transgenderism in children have rapidly increased in recent years in the U.S., which has sparked discussions between parents, schools, policymakers, and medical professionals alike over how to discuss and treat the issue. On one end of the spectrum, activist groups and a vocal subset of the medical establishment have promoted what is euphemistically known as “gender-affirming care,” whereby children with transgender inclinations are being encouraged to undertake potentially irreversible surgical and hormonal interventions with unknown long-term consequences. The interventions range from preventing normal pubertal development to surgical procedures removing healthy breast tissue and genitalia. Recognizing the potential for significant harm, and with over 300,000 youths between the ages of 13–17 in the U.S. now identifying as transgender, some states are setting policies designed to protect children from such irreversible treatments made at a critical time in their physical, mental, and emotional development (Herman, Flores, & O’Neil, 2022).

By castigating those who disagree with these procedures as “transphobic,” the people calling for the immediate normalization of these surgeries and treatments have dismissed valid concerns. Many important questions have arisen based on emerging evidence from systematic reviews, whistleblowers, detransitioners, and findings of a new clinical phenomenon of rapid onset of the condition in adolescence rather than early childhood. The fervor of the argument for “gender-affirming care” is not matched by any strength of evidence establishing that such treatments are either safe or effective for promoting long-term well-being. On the contrary, Americans have significant reasons to be instead concerned about the effects of such radical interventions undertaken on children.

Indeed, the American people recognize the riskiness of such treatments on children, with most registered voters believing that “gender-affirming care” for children should be illegal. Moreover, around 85% of children with gender dysphoria do not carry this condition into adolescence—making the notion of using permanent treatments to address temporary conditions quite troubling (Hembree et al., 2017). Nevertheless, many medical professionals in the U.S. are using an “affirm-early/affirm-often” approach when it comes to dealing with children who have gender dysphoria, and they often recommend puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and/or sex-change surgeries.

Though other nations have shied away from such an approach in recent years, a recent review of eligibility criteria for sex-reassignment surgery found that children in the U.S. have access to the procedure at younger ages than minors in Western and Northern Europe (Do No Harm, 2023a). The same holds true with the prescription of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. Today, some states in the U.S. have more permissive laws than Western and Northern European nations. Not only is there little evidence that some of these “treatments” do anything to benefit the mental health of a child, but studies have shown mounting evidence that transgender drugs and surgical procedures have negative side effects for children. Moreover, many of the drugs prescribed to children for such procedures are prescribed for unapproved use.

A contrasting approach to the prevailing “gender-affirming” philosophy of interventions does exist. It can be described as the “first, do no harm” model, which holds that the risks of medical and surgical interventions outweigh the benefits, and states that doctors should focus on other options, such as exploratory psychotherapy, while ensuring strong mental and social support (Schwartz, 2021; SEGM, 2021a). The non-profit “Do No Harm,” which consists of numerous physicians and healthcare professionals, has started an education campaign to protect minors from gender ideology and has, like other non-profit groups, concluded that it is appropriate for state lawmakers to now intervene (Do No Harm, 2023a; Do No Harm, 2023b; Do No Harm, 2023c; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). The Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) has also highlighted the lack of quality evidence and recommended that the medical community urgently address concerns with current practices while endorsing the approach to “first, do no harm” (SEGM, 2023; SEGM, 2021b). Policymakers in the U.S. should consider all of this data and adopt policies that protect children from potentially harmful and irreversible procedures.

This report builds upon the foundation set by Do No Harm and SEGM by compiling knowledge from a diversified set of resources to understand the history and diagnosis of gender dysphoria, explore different treatment models for the condition, and investigate how other countries approach the issue relative to how it is dealt with in the U.S. Finally, this report reviews how the American people perceive this issue and then outlines state actions to protect children.

Section One: Defining Gender Dysphoria and Understanding the Role of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

To fully understand pediatric gender medicine, it is critical to start with the diagnostic history of gender dysphoria and the evolution of the primary tool used by clinicians to make the diagnosis. Originally published in 1952 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is considered the “go-to” reference for the characterization and diagnosis of mental disorders in the U.S. and much of the world (Kawa & Giordano, 2012).

The DSM is translated into over 20 languages and is the leading mental disorder diagnostic resource, exerting heavy influence in the field of psychiatry and across society over the last 70 years (Kawa & Giordano, 2012). This resource is used by clinicians, researchers, policymakers, courts, and insurance companies alike. The DSM is now on volume five, with each edition reflecting a change of definitions and inclusions intended to represent current medical thinking—some with significant impact. As an example, between DSM-II to DSM-III, the number of mental disorder categories rose from 182 to 265, partly due to a shift from considering mental disorders as psychological states to considering them discrete disease categories based on symptoms—a shift one source noted as “an attempt to ‘re-medicalize’ American psychiatry” (Kawa & Giordano, 2012). The most recent version, DSM-5 (the version updated its notation from Roman numerals to numbers), included nearly 300 mental disorders and took 14 years of planning and preparation to publish (Suris et al. 2016).

It was not until DSM-III (1980) that any term related to gender dysphoria was included. The term used in the DSM-III was “transsexualism,” and then was later changed to “gender identity disorder in adults and adolescents” in the DSM-IV released in 1994. In 2013, the DSM-5 was released and again changed the term to “gender dysphoria” (APA, 2017). Given the above history regarding the DSM, it is also important to note that the symptom-based disease categorization of the DSM-III led to an increase in psychopharmacological interventions.

The revised text version of the DSM-5, the DSM-5-TR, was published in 2022. This edition included significant updates, notably the direction to use “culturally-sensitive language,” such as changing “desired gender” to “experienced gender” and changing “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical treatment” (APA, 2022a).

The DSM-5-TR definition of gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults is as follows:

“ … a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following:

-

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

-

A strong desire to be rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender (or in young adolescents, a desire to prevent the development of the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

-

A strong desire for the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender

-

A strong desire to be of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

-

A strong desire to be treated as the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

-

A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender),”

(APA, 2022b).

Additionally, the DSM-5-TR definition of gender dysphoria in children is as follows:

“ … a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least six of the following (one of which must be the first criterion):

-

A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence that one is the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

-

In boys (assigned gender), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong preference for wearing only typical masculine clothing and a strong resistance to the wearing of typical feminine clothing

-

A strong preference for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy play

-

A strong preference for the toys, games or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender

-

A strong preference for playmates of the other gender

-

In boys (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically masculine toys, games, and activities and a strong avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically feminine toys, games, and activities

-

A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

-

A strong desire for the physical sex characteristics that match one’s experienced gender,”

(APA, 2022b).

Notably, the diagnostic criteria for both include association of the condition with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (APA, 2022b).

Because of the millions of lives impacted by the DSM, researchers have raised concerns about potential political and financial biases of authors contributing to the clinical reference book. The Society for Humanistic Psychology has been a leader in elevating concerns over the DSM-5 and was critical in launching a petition of over 15,000 concerned mental health professionals and groups from around the world (Kamens, Elkins, & Robbins, 2017). Topping the list of their concerns is a conflict of interest among the authors. Many DSM panel members have direct financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry, and several of the disorders call for pharmacological treatment as the first-line intervention (Cosgrove & Krimsky, 2012).

It is also worth noting that the DSM-5-TR included other considerable “cultural changes.” Published in 2022 as a text revision to the latest DSM-5, the DSM-5-TR changed (among other things) the term “race/racial” to “racialized” to underscore that race is a social construct (Blanchfield, 2022). It also changed “Latino/Latina” to “Latinx” to promote gender equality and discontinued the use of “minority” and “non-White” to avoid creating a social hierarchy (Blanchfield, 2022).

The DSM-5 was designed to include cultural, racial, and gender considerations. As a part of their review and rationale for updating the DSM-5, “a DSM-5 Culture and Gender Study Group was appointed to provide guidelines for the work group literature reviews and data analyses that served as the empirical rationale for draft changes” to ensure that cultural factors were included in revisions (Regier et al. 2013). Although these considerations were included in the DMS-5, updates were made in the DSM-5-TR in “response to concerns that race, ethnoracial differences, racism and discrimination be handled appropriately” (APA, 2022c). The strategies used to address these concerns were 1) a 19-person review committee on cultural issues and 2) a 10-person Ethnoracial Equity and Inclusion Work Group made up of practitioners from diverse backgrounds (APA, 2022c). Given that the DSM is the mental disorder diagnostic tool used in much of the world, it is critical to note the changes that have been made in response to social, cultural, and political pressures rather than a change in medical data and scientific evidence.

Section Two: The Treatment of Gender Dysphoria

Today, U.S. government agencies and many medical professional groups have signaled their support for these types of treatments. Under the Biden Administration, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services states that for children, “early gender-affirming care is crucial to overall health and well-being” (HHS Office of Population Affairs, n.d.). Many medical professionals in the U.S. accept an “affirm-only/affirm-early” approach to gender transition, which strives to implement interventions (including hormonal or surgical) to help a child better align with his or her “gender identity” (Do No Harm, 2023a). Though surgery and hormonal treatments are permanent, evidence indicates that about 85% of cases of children with gender dysphoria do not persist into adolescence (Hembree et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) embraces the approach of early medical intervention for children and adolescents (Rafferty et al., 2018).

Along with the AAP, multiple medical professional guidelines explain that the appropriate treatment of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents should be used in a “gender-affirmative care model” (GACM) and may include:

-

Psychotherapy;

-

Hormone or Puberty Blockers;

-

Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy; and/or

-

Sex Reassignment Surgery

The GACM allows youth to progress through some or all interventions depending on timing and pubertal maturity (Brown & Stathatos, 2022; Rafferty et al., 2018). Psychotherapy has an important distinction; it has a primary role in another model of care known as “first, do no harm” (Rafferty et al., 2018; Schwartz, 2021). In this model, medical and surgical interventions are considered to carry greater risk than benefit for youth, a position well summarized by psychologist David Schwartz, Ph.D.:

… in the treatment of children and adolescents, no matter what the diagnosis, encouraging mastectomy, ovariectomy, uterine extirpation, penile disablement, tracheal shave, the prescription of hormones which are out of line with the genetic make-up of the child, or puberty blockers, are all clinical practices which run an unacceptably high risk of doing harm (SEGM, 2021).

Many of the puberty blockers and cross-sex hormone therapies used to treat gender dysphoria in children are prescribed off-label (for a purpose not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)). Therefore, they can pose a greater risk, including the risk of unknown long-term effects, to the children who receive them. In 2021, the Texas Attorney General launched an investigation into two pharmaceutical companies for allegedly advertising and promoting the off-label use of puberty blockers without disclosing any of their risks (Attorney General of Texas, 2021). In 2022, the FDA also issued a new warning for commonly used puberty blockers, including “recommendations to monitor patients taking GnRH agonists for signs and symptoms of pseudotumor cerebri, including headache, papilledema, blurred or loss of vision, diplopia, pain behind the eye or pain with eye movement, tinnitus, dizziness and nausea” (FDA, 2022). Despite these facts, a growing number of children are being prescribed these drugs for unapproved uses.

There are significant side effects and limited research on the long-term impacts and efficacy of various treatments used in a GACM of gender dysphoria in children. Patients and parents are advised that the use of puberty blockers in children may be associated with lower bone density, stunted growth, fertility issues, and underdevelopment of genital tissue (Mayo Clinic, 2022; St. Louis Children’s Hospital, n.d.; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). Moreover, a study conducted in England demonstrated similar negative side effects, such as lowered bone density and stunted growth, without showing a change in the psychological well-being of the children studied (Carmichael et al., 2021, p. 18; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). Cross-sex hormones prescribed to children also demonstrated a plethora of side effects, including blood clots in veins and permanent infertility (CDC, n.d.; NHS England, 2016, p. 8; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). Importantly, cross-sex hormones can result in the development of secondary sex characteristics such as the development of breasts in male-to-female patients and deepening of the voice in female-to-male patients that, though desired at the time, are irreversible (NHS England, 2020b; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). Moreover, the neurocognitive effects of pubertal suppression are unknown. International experts are in consensus about the need to assess long-term effects and have stated that: “Taken as a whole, the existing knowledge about puberty and the brain raises the possibility that suppressing sex hormone production during this period could alter neurodevelopment in complex ways—not all of which may be beneficial” (Chen et al. 2020).

Proponents of a GACM frequently claim that it is the only way to improve mental health and reduce suicide risk in youth. However, a 40-year cohort study from Sweden on transsexual individuals undergoing sex-reassignment surgery—one of the most comprehensive long-term studies available—found that high suicide risk persisted after surgical procedures at a rate 19.1 times higher than the general population (Dhejne et al., 2011). Another Swedish population study with one of the largest cohorts established to date evaluated (in a corrected analysis from the original publication) mental health outcomes among transgender individuals who received surgical interventions and those who did not and found “no advantage of surgery in relation to subsequent mood or anxiety disorder-related health care visits or prescriptions or hospitalizations following suicide attempts” (Branstrom, & Pachankis, 2019; Kalin, 2020).

Treatment protocols for gender dysphoria often follow the guidelines of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the Endocrine Society (an international medical professional association), and the American Association of Pediatrics (AAP). However, a recent review article from the Manhattan Institute outlined significant flaws with the recommendations from each organization based on the evidence available in the academic literature and from best practices in other countries (Sapir, 2022). Notably, the AAP position paper, which supported early affirmation and treatment of gender dysphoria in childhood, was fact-checked by psychologist James Cantor, Ph.D., of the Toronto Sexuality Center. Dr. Cantor found that the AAP position paper omitted information regarding the low frequency of gender dysphoria persisting from childhood to adolescence (Cantor, 2020). He also found that the AAP paper, when rejecting “watchful waiting,” misrepresented citations regarding the approach that aims to put pharmacologic or surgical intervention on hold while the patient receives other supportive care and counseling (Cantor, 2020).

Additionally, the Endocrine Society’s “clinical practice guideline” from 2017 assesses the quality of evidence for each of its recommendations (Hembree et al., 2017). All six recommendations specifically related to treatment for adolescents found only a “low” or “very low” quality of evidence (Hembree et al., 2017). One recommendation (2.5) that is listed as a weak recommendation with a very low quality of evidence is particularly concerning:

We recognize that there may be compelling reasons to initiate sex hormone treatment prior to the age of 16 years in some adolescents with GD [gender dysphoria] / gender incongruence, even though there are minimal published studies of gender-affirming hormone treatments administered before age 13.5 to 14 years. As with the care of adolescents 16 years of age, we recommend that an expert multidisciplinary team of medical and MHPs [mental health providers] manage this treatment (Hembree et al., 2017).

The WPATH guidelines rely heavily on the experience of a specific Dutch protocol, but there are many methodological concerns with how conclusions are supported and how they apply to the current clinical reality (Coleman et al., 2022; Sapir, 2022). A recent review of the Dutch protocol methodology outlines the following three primary concerns:

(1) subject selection assured that only the most successful cases were included in the results; (2) the finding that “resolution of gender dysphoria” was due to the reversal of the questionnaire employed; (3) concomitant psychotherapy made it impossible to separate the effects of this intervention from those of hormones and surgery (Abbruzzese, Levine, & Mason, 2023).

Importantly, there have been challenges replicating the Dutch protocol results largely due to concerns of significant selection bias (Abbruzzese, Levine, & Mason, 2023). This fact and the forthcoming discussion about the changing demographics of youth gender dysphoria in the U.S. lend credence to the position that the Dutch protocol cannot adequately justify the current practice patterns in America.

Further, political biases exist within WPATH and appear to be reflected in their guidelines. Dr. Bowers, a transgender woman and world-renowned gender surgeon who is on the board of WPATH, was asked if the organization had been welcoming to a wide variety of doctors’ viewpoints. In response, Dr. Bowers said: “There are definitely people who are trying to keep out anyone who doesn’t absolutely buy the party line that everything should be affirming and that there’s no room for dissent” (Shrier, 2021, para. 12; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). A second doctor on the board of WPATH, Dr. Erica Anderson, submitted a co-authored op-ed to the New York Times expressing concerns that transgender children were receiving reckless healthcare and that WPATH was recommending puberty blockers too early in puberty, but the Times declined to publish her piece (Shrier, 2021, para. 6, 7, & 50; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). The piece, which was titled “The mental health establishment is failing trans kids: Gender-exploratory therapy is a key step. Why aren’t therapists providing it?” was later published in the Washington Post (Edwards-Leeper & Anderson, 2021). It was co-authored with another clinical psychologist and member of the WPATH, Dr. Laura Edwards-Leeper, with the core message that rushed medical treatment without proper evaluation and therapy puts children at risk (Edwards-Leeper & Anderson, 2021).

In addition to the Do No Harm group, other groups of medical professionals have alternative views on the ideal way to proceed in this area. SEGM is a group made up of over 100 clinicians and researchers from a range of disciplines who are concerned about the quality of evidence being used to recommend medical and surgical interventions as first-line treatment for young patients with gender dysphoria (SEGM, n.d.(b)). They offer an alternative clinical position based on their expertise and review of the current evidence:

SEGM firmly believes that medical decisions must remain between patient and clinicians, without political interference. However, we also believe that it is incumbent on US medical societies to urgently examine the evidence base for hormonal and surgical interventions for youth using rigorous systematic research methods. Given the results of the recent systematic evidence review conducted by NICE, which concluded that the evidence of benefits of these interventions is of very low certainty and the risk/benefit profile is unclear, SEGM believes that exploratory psychotherapy should be first-line treatment for gender dysphoric people age 25 and under (SEGM, n.d.(a)).

Section Three: A Comparison: Trends in the U.S. vs. Other Nations on the Treatment of Gender Dysphoria in Children and Adolescents

A recent study estimated that nearly 1.6 million people ages 13+ identified as transgender in the U.S. and denoted a generational shift because rates of transgenderism in children are growing at a much faster rate than in adults (Herman, Flores, & O’Neil, 2022). In fact, now nearly 20% of people who identify as transgender are aged 13–17, meaning around 300,000 children are now identifying as transgender (Herman, Flores, & O’Neil, 2022). For added perspective, one must consider that nearly 20% of all people who identify as transgender in the U.S. are children 13–17, yet that age range only makes up 8% of the U.S. population (Herman, Flores, & O’Neil, 2022). Additionally, the number of children known to be on puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones in the U.S. more than doubled in just four years—from 2,394 in 2017 to 5,063 in 2021 (Do No Harm, 2023a; Terhune, Respaut, & Conlin, 2022). Furthermore, one study found that more than 120,000 children in the U.S. were diagnosed with gender dysphoria during the same four-year period (Respaut & Terhune, 2022). Experts and researchers in the field are concerned with rates in a specific sub-group—adolescent girls—and have called for a greater understanding of “rapid onset gender dysphoria” as a distinct clinical phenomenon (Sinai, 2022).

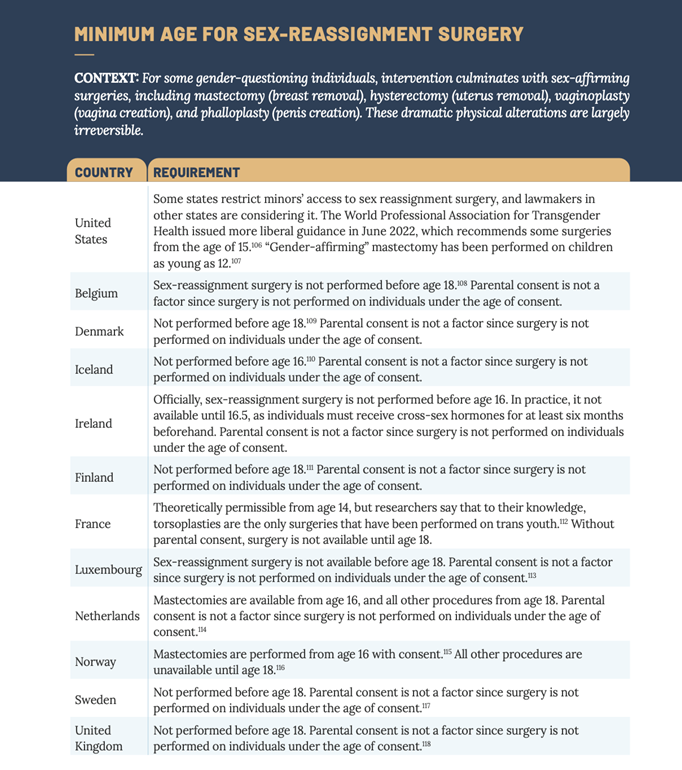

As noted above, the medical community in the U.S. has opted to broadly take an “affirm-early/affirm-often” approach when it comes to treating gender dysphoria in children. By labeling the full spectrum of interventions used to transition youth—from social to puberty-blocking to cross-sex hormones and to surgery—as “affirming,” many have tried to categorize all other treatments into a binary category of “non-affirming.” In doing so, they have framed it as harmful, thereby limiting valid alternatives such as psychotherapy (D’Angelo et al., 2020). More than 60 pediatric gender clinics and more than 300 clinics that provide hormonal interventions to children in the U.S. now exist (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 12). When measured against other Western and Northern European countries, the U.S. has the most clinics providing treatment for the gender transition of children and the most permissive laws regarding the legal and medical gender transition of children (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 3 & p. 12). Below is a chart from Do No Harm that outlines the laws regarding sex-assignment surgery in the U.S. in comparison to the laws in Western and Northern European nations:

This data clearly demonstrate that the U.S. allows doctors to perform sex-reassignment surgery on children at a younger age than most comparable nations (12 years old in some cases in the U.S.) (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 11). Most Western and European nations protect minor children from sex-reassignment surgeries by requiring patients to reach age 18 (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 11). The U.S. is in a similar position regarding puberty blockers for children, which clinical guidelines do not recommend until puberty (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 9). Nevertheless, many U.S. physicians are prescribing puberty blockers as early as 8 years old (reportedly at the earliest sign of puberty), and, in some states, parental consent for these drugs is not needed. (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 9). In Oregon, children 15 and over do not need parental consent, and taxpayers pay for puberty blockers for children through Medicaid (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 9). This practice appears to be an outlier in comparison to many other countries where puberty blockers are typically not given until children reach a specific stage of puberty (Tanner Stage II) or until they reach the age of 12 (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 9).

The use of cross-sex hormones is likewise another area where some states in the U.S. have more permissive policies than many other countries in the world (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 10). Cross-sex hormones have been given to some children in the U.S. under 13 years old (state laws vary on this), and Oregon again has the most permissive laws for this treatment (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 10). It now allows for these drugs to be used at the age of 15 without consent and with taxpayer funding (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 10). In contrast, the vast majority of other countries examined in the Do No Harm report do not allow for these hormones until age 16 (Do No Harm, 2023a, p. 10).

In recent years, the path of the U.S. has diverged significantly from the path of other countries. While the U.S. has continued to loosen protocols around puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and sex-reassignment surgeries, other countries have begun tightening their protocols and shifting away from the “affirm-early/affirm-often” approach based on emerging evidence from thorough and systematic evidence reviews. In June 2020, Finland recommended psychosocial support to treat gender dysphoria in minors (Council for Choice in Health Care in Finland, 2020). If youth go on to experience severe and persistent gender-related anxiety, they can then be referred to centralized research clinics on gender identity where hormonal treatment through a research protocol is considered on a case-by-case basis only if strict criteria are met (Council for Choice in Health Care in Finland, 2020). Importantly, the Finnish guidelines do not allow surgical treatments stating that they “are not part of the treatment methods for dysphoria caused by gender-related conflicts in minors” (Council for Choice in Health Care in Finland, 2020). Also in 2020, the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service of England released a study stating that children receiving puberty blockers for gender dysphoria experienced little to no change in their psychological well-being (Barnes & Cohen, 2020; Carmichael et al., 2021; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). A study completed by England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in October 2020 found the studies evaluating the use of puberty blockers to have “very low certainty” in the “critical outcomes of gender dysphoria and mental health” (NICE, 2020a p. 45; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). In 2022, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare updated its recommendations for the care of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria assessing that “the risks of puberty blockers and gender-affirming treatment are likely to outweigh the expected benefits of these treatments” and cautions the healthcare system regarding their use (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2022 p. 3; Brown & Stathatos, 2022).

In addition to systematic reviews, emerging evidence in the academic literature and in mainstream news about the experience of “detransitioners” is leading to more questions than answers. Detransitioners are defined as those individuals who revert back to living as their biological sex after transitioning, and many medical professionals and the general public are now asking more questions about the care these children and adolescents receive. In a key study of 100 detransitioners, more than half (55%) did not have an adequate evaluation from a doctor or mental health professional before starting to transition, and just one in four (24%) told their clinician they had detransitioned (Littman, 2021).

The U.S. has clearly taken a radical stance regarding the treatment of gender dysphoria in children, while other countries are simultaneously questioning the data and evidence that support the use of hormone therapy and puberty blockers in children. Given the irreversible nature of these treatments, emerging evidence that high numbers of people regret undergoing them as minor children, and rising international awareness that an “affirm-only/affirm-early” approach may be causing inadvertent harm, medical policymakers in the U.S. should strongly consider adopting a more cautious approach.

Section Four: The Position of the American People on “Gender-Affirming Care”

A series of national polls from Scott Rasmussen throughout 2022 demonstrates that the plurality of Americans surveyed does not align with the medical community’s current recommendations. The findings may be largely based on a common-sense approach and informed by other societal norms to protect children from potentially damaging and irreversible decisions until they reach adulthood. Current examples are the legal drinking age of 21 years old, voluntary military participation at 18 years old, and informed parental consent for all aspects of daily life—from field trip permission slips to major medical interventions.

Scott Rasmussen National Survey of Registered Voters

October 25–27, 2022

-

When given a choice between two candidates for Congress, 56% of registered voters responded that they would vote for the candidate who said it should be illegal to provide surgery to help children transition from one gender to another. 25% of registered voters responded that they would vote for the candidate who said it would be immoral to restrict surgery that helps children transition from one gender to another.

Scott Rasmussen National Survey of Registered Voters

October 18–20, 2022

-

72% of registered voters do not believe schools should teach children that they can change their gender.

-

59% of registered voters believe it should be against the law to provide “gender-affirming care” to children, which involves puberty blockers or surgery to help transition a boy to a girl or a girl to a boy.

-

56% of registered voters believe conducting gender-transition surgery on children is a form of child abuse.

-

73% of registered voters either strongly or somewhat disagree with people who advocate that children should be allowed to receive “gender-affirming care,” including puberty blockers and surgery, without the permission of their parents.

-

60% of registered voters believe it is a form of child abuse when a teacher or school encourages students to change their gender identity.

Scott Rasmussen National Survey of Registered Voters

July 12–13, 2022

-

When asked, “Should a child under 18 be encouraged to explore and define his or her own gender identity, or should he or she be encouraged to accept the gender that aligns with his or her biological sex?” 49% said a child should accept the gender that aligns with his or her biological sex. 32% said a child should define his or her own gender identity, and 19% were not sure.

Scott Rasmussen National Survey of Registered Voters

March 10–12, 2022

-

When asked, “Some people advocate “gender-affirming care” which involves surgery to alter a person’s physical and sexual characteristics to match their gender identity, which can be used to transition a boy to a girl or a girl to a boy. Should it be against the law to perform such a surgery on young children?” 63% of registered voters said “yes.”

-

66% of registered voters said it should be against the law to perform such a surgery on anyone under 18.

Section Five: State Actions to Protect Children

The regulation of medical care is under the purview of states, and states have started to take action to protect children. The combination of concerning safety evidence and international trends outlined above supports the need for restrictions on medical and surgical gender transition interventions in children and adolescents. One option states can take is to delegate this responsibility to the state medical board, which could evaluate all the evidence and provide guidance to enact restrictions. Florida implemented this approach in 2022—first with guidance from the Department of Health in April and then with a report from the Agency for Health Care Administration in June (FL DOH, 2022a, FL ACHA, 2022). These releases were immediately followed by a letter from the Surgeon General to Members of the Board asking them to review the evidence and guidance to establish a standard of care for “these complex and irreversible procedures” (FL DOH 2022b). The Florida Board of Medicine voted in November 2022 to ban the hormonal and surgical treatment of gender dysphoria in children (Izaguirre, 2022). This approach is a policy lever to preserve the delegative nature of the nuanced medical decision-making to medical experts. However, as seen in the COVID-19 pandemic, state medical boards do not always make evidence-based decisions when providing guidance, which indicates a need for additional policy options for state lawmakers (Tahir, 2022).

In 2021, Arkansas became the first state to pass such restrictions into law with the Save Adolescents from Experimentation (SAFE) Act (HB 1570, 2021; Bryan, 2021; Brown & Stathatos, 2022). The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) quickly filed suit resulting in a preliminary injunction on the restrictions, and the case is currently awaiting a decision in the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals (ACLU, n.d.). At least 18 other states are considering similar actions, and Utah became the first state to enact legislation to protect children in 2023 (Associated Press, 2023).

After recently blowing the whistle on The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, Jamie Reed began cooperating with the Missouri Attorney General to investigate the center. Following four years of working as a case manager in the clinic, she stated “… I could no longer participate in what was happening there. By the time I departed, I was certain that the way the American medical system is treating these patients is the opposite of the promise we make to ‘do no harm.’ Instead, we are permanently harming the vulnerable patients in our care” (Reed, 2023). Now, Ms. Reed is working with Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey, who has launched a multi-agency investigation into the St. Louis Transgender Center on February 9, 2023, for harming hundreds of children (MO Attorney General’s Office, 2023). The investigation is based on Ms. Reed’s sworn affidavit signed on February 7, 2023 (MO Attorney General’s Office, 2023). Missouri is one of several states considering legislative action this session that would create more than one mechanism to resolve the disturbing issues raised by Ms. Reed. Though this is largely a state issue, Ms. Reed, who is self-described as “politically left of Bernie Sanders,” believes there should be a national moratorium on these interventions for children and adolescents until the American people know more (Reed, 2023).

Another high-profile story on youth sex-reassignment surgeries at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) led Tennessee Governor Bill Lee to call for an investigation of the pediatric transgender clinic in September 2022 (Kruesi, 2022a). VUMC subsequently paused the surgeries in October of 2022 to review their practices (Kruesi, 2022b). Tennessee lawmakers in both chambers have prioritized legislation this session that protects children by banning gender transition interventions for minors—Senate Bill 1 has already passed, and House Bill 1 is expected to pass imminently (Brown, 2023).

Although critics argue that these state policies limit necessary medical care and risk the mental health of transgender youth, all should understand that the restrictions on gender transition interventions do not limit the mental health and supportive treatments available for vulnerable children and adolescents. Instead, the policies seek to increase the “first, do no harm” principle of healthcare and protect children from an area of uncertain science with emerging evidence that is rapidly changing international best practices. Indeed, an evidence review completed for the National Health Service in England found that “any potential benefits of gender-affirming hormones must be weighed against the largely unknown long-term safety profile of these treatments in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria,” (NICE, 2020b, p. 14).

National policymakers and, specifically, public health officials would be wise to both listen to Ms. Reed and follow the example of Florida Surgeon General Dr. Ladapo in independently gathering data and taking action to ensure the safety of America’s children.

Conclusion

The U.S. is an outlier among peer European nations in its “affirm-early/affirm-often” approach to medical and surgical interventions for gender dysphoria in children. The low-quality evidence of the current clinical practice guidelines and the unknown long-term consequences merit additional safety measures for children. State policymakers can implement solutions through their medical boards, through legal action, and in their 2023 legislative sessions, while the medical community should more broadly adopt a “first, do no harm” model when treating children with gender dysphoria.

Works Cited