Issue Brief: The Inflationary Impact of Expanded ACA Subsidies on Health Insurance Premiums and Alternative Options to Put Americans First

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The Big Government Socialism Bill will lead to higher healthcare spending through inflationary subsidy structures that largely benefit insurance companies.

- An estimated 1.6 million people will lose their employer-sponsored health insurance and be forcibly transitioned to government subsidized coverage in the individual market.

- The majority of new coverage from taxpayer dollars will subsidize costs for Americans whose income is greater than 400 percent of the federal poverty level, about $106,000 for a family of four.

- The Big Government Socialism Bill will lead to a continued increase in U.S. healthcare spending while Americans will continue to see less choices and flexibility in obtaining the health coverage best for them.

- Alternative health benefits provide an example for potential actions that states and employers can take to increase affordable, quality coverage options to Americans.

OVERVIEW

President Biden’s banner policy plan, the Build Back Better Act, otherwise known as the “Big Government Socialism Bill” (BGSB), is being advertised as a solution to a top concern of many Americans—the rising cost of health insurance premiums.[1],[2] The bill passed the House of Representatives on November 19, 2021, but does not have the votes to pass in the Senate in its current form.[3] In reality, the bill’s healthcare provisions would do nothing to solve some of the worst problems with the Affordable Care Act (ACA): the trend of rising healthcare costs with no guarantee of better access to care.

The BGSB would extend the ACA premium tax credit/subsidy temporary expansions already implemented by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) through the year 2025.[4],[5] ARPA expanded ACA subsidies in two ways:

- made Americans making over 400 percent Federal Poverty Level (FPL) eligible to receive subsidized coverage; and

- increased the amount of subsidy funding received by those between 100 to 150 percent FPL.[6]

These expansions are set to expire at the end of 2022 under ARPA, but early versions of the BGSB attempted to make this expansion permanent rather than ending in 2025, hinting that this is the true policy goal.[7]

This issue brief will review the ACA’s initial contribution to premium inflation, the impact of the BGSB’s subsidy extension provisions, and alternative solutions that prioritize care over coverage.

BACKGROUND ON ACA SUBSIDY STRUCTURE AND REQUIRED CONTRIBUTIONS

The ACA, also known as Obamacare, was passed in 2010 with the goal of increasing the number of Americans covered by health insurance. The law attempted to make individual insurance more affordable by creating premium tax credits to subsidize the cost of health insurance purchased through individual marketplaces for low-income individuals to achieve this goal. Subsidies were made available to Americans with incomes between 100 to 400 percent FPL and could be applied to any plan on the marketplace, except catastrophic plans.[8] A new system of four-tiered plans (bronze, silver, gold, and platinum) was developed based on a cost-sharing ratio of the deductible to plan coverage.[9] Open enrollment for the marketplaces began on October 1, 2013, and coverage began in 2014.[10] The amount of subsidy a person receives is determined by an equation that considers the cost of the second-lowest cost silver level plan in the person’s area and the person’s income. This plan is referred to as a “benchmark plan.”

There is also a “required individual contribution” that enrollees must pay towards premiums. The ACA established required contributions that ranged on a sliding scale from 2.06 percent of household income for people with income between 100 percent and 133 percent FPL to 9.78 percent of income for people with income from 300 to 400 percent FPL.[11]

The passage of ARPA in 2021 changed required contributions, effectively eliminating them for those between 100 to 150 percent FPL by reducing it to 0 percent of income.[12] ARPA also lowered the required contribution to 8.5 percent for those at 400 percent FPL and above. Americans with incomes between 100 to 150 percent FPL currently make up 42 percent of enrollees in ACA plans,[13] meaning that two in five enrollees received expanded subsidies with no cost-sharing responsibility for premiums.

RISING COSTS AND DECREASING ENROLLMENT

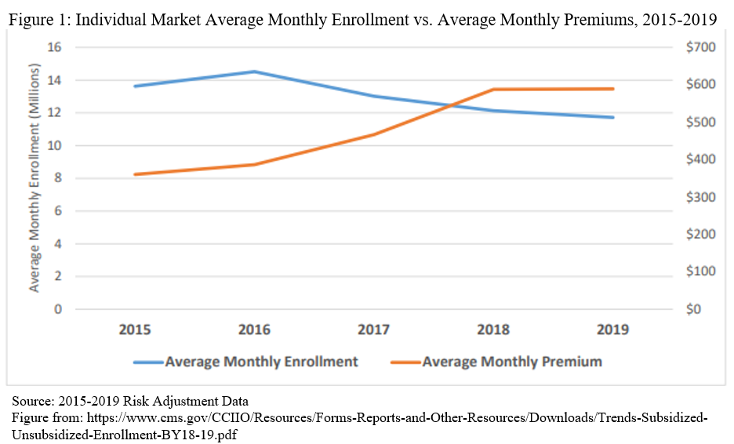

Despite its name, coverage under the ACA quickly became unaffordable for many. Average monthly premiums in the individual health insurance market increased by 143 percent from 2013 to 2019, rising from an initial average of $242 to $589.[14] With average yearly premium expenses over $7,000, it is clear that the ACA did not deliver on President Obama’s 2008 campaign promise to reduce average premiums by $2,500 per year for the typical family.[15]

The number of uninsured adults in the U.S. decreased from 20.5 percent in 2013 to 12.9 percent in 2019, with a nadir of 12.1 percent in 2016.[16] Most of the decrease in the number of uninsured adults was from Medicaid expansion, with an increase of 14 million in Medicaid enrollment from mid-2013 to March 2020.[17] Enrollment in the individual market significantly underperformed projections, however. In 2010, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that nearly 25 million people would obtain insurance coverage through the Exchanges in 10 years.[18] The actual effectuated enrollment in 2020 was only 10.4 million.[19] This is an estimated gain of only 2 million more than expected without the ACA.[20]

There is an inverse relationship between premiums and enrollment. Figure 1 demonstrates that the rise in average monthly premiums coincided with a decrease in average monthly enrollment in the individual market.

Enrollees ineligible for subsidies—including many self-employed and early retirees—were particularly impacted by rising premiums. From 2016 to 2019, unsubsidized enrollment declined 45 percent nationally, from 6.2 million to 3.4 million.[21] During this same period, premiums increased 52 percent nationally.[22] The number of uninsured adults increased by 1.15 million among those with earnings over 400 percent FPL, which accounted for 73 percent of the total increase in uninsured adults from 2016 to 2019 (1.58 million).[23]

Premiums are not the only healthcare costs that the ACA has impacted. Deductibles, which are also a significant consumer-facing cost, have increased. Since 2014, the average median deductible across all metal levels[24] has increased from $2,528 to $3,375 in 2021, a 34 percent jump.[25] Lower-tier plans with smaller premiums tend to have even higher deductibles. Silver benchmark plans, which are the most popular, saw the highest increase of 59 percent, from a median of $3,070 in 2014 to $4,879 in 2021. Rising deductibles further decrease the affordability of healthcare plans on the exchange.

This phenomenon of unsubsidized enrollees leaving the ACA market demonstrates just how unaffordable ACA plans have become, even for the four out of ten Americans who have annual incomes above 400 percent FPL ($51,040 for individuals and $104,800 for a family of four[26]).[27] For Americans at these income levels to be priced out of health insurance indicates the urgent need to address the root cause—rising healthcare costs—rather than taking a band-aid approach of paying for ever-rising premiums with ever-rising taxpayer-financed subsidies that only encourage more spending.

CHOICE IS MORE LIMITED UNDER ACA

Not only has the ACA increased costs for consumers, but it also greatly reduced the number of plans available to enrollees. Before the passage of the ACA in 2013, 395 insurers sold plans in the individual market in the U.S. In 2021, 253 insurers offered plans, meaning that consumers do not benefit from as much competition as before the ACA.[28] Insurer participation in the ACA market hit a low point of 181 insurers nationally in 2018. Since then, insurer participation has improved, but the individual market still has one-third fewer competitors than before the ACA took effect.

Premium subsidies are determined by local benchmark plans, so it is also worth noting that this trend also holds true at the county level. At the beginning of the ACA’s lifetime in 2014, about half, or 52 percent, of U.S. counties had only one or two insurers offering coverage.[29] This problem grew much worse over the next few years, with 82 percent of U.S. counties having only one or two insurers offering ACA plans in 2018. This trend has been improving since then, with 53 percent of counties having one or two insurers in 2021, still only marginally better than in 2014.[30] Nearly one in ten U.S. counties still have only one choice of insurer, meaning that those shopping for individual coverage have no option but a single plan.

In addition to rising premiums, enrollees in ACA plans are losing the ability to choose their doctor as covered provider networks for ACA plans shrink. Health plans on the individual market with more restrictive networks increased over 75 percent from 2016 to 2019.[31] While narrow network design can help keep premium costs lower for enrollees, it may mean that preferred doctors or hospitals are not covered by a chosen insurance plan. This highlights another infamous broken ACA promise from President Obama: “If you like your doctor, you can keep your doctor.”[32]

IMPACT OF THE BIG GOVERNMENT SOCIALISM BILL’S ACA PROPOSALS

Subsidies Contribute to Inflated Costs

The structure of the premium tax credit subsidies implemented by the ACA is the major driver of rising premiums. Subsidies create a disconnect between the actual cost of premiums for plans and the amount consumers spend out of pocket, which can insulate enrollees from moderate price increases.[33] For reference, individuals enrolled in an ACA plan saw an average national monthly health insurance cost of $612 before tax subsidies and $143 after tax subsidies were applied—a $469 difference.[34]

Since federal subsidies are tied to benchmark plans, they increase alongside annual premium increases. Given that families are only expected to pay up to a predetermined percentage of their income to purchase a benchmark plan, ACA subsidies cover any residual premium and increase in lockstep with rising premiums.[35] This subsidy design makes subsidy recipients quite price-insensitive, making prices more likely to rise. Put plainly, insurance companies have the power to raise premiums for benchmark plans, and the government simply gives consumers more money to afford it better. A report by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight found that “The structure of the premium tax credit also encourages premium inflation because the amount of the subsidy is linked to the overall cost of the health plan.”[36] ACA policies, therefore, have an inflationary relationship with premiums in individual market plans causing costs to go up for the federal government without corresponding increases in coverage by insurance companies.[37]

By the end of 2021, overall U.S. inflation had reached a 39-year high, and 92 percent of Americans currently say they are worried about inflation.[38],[39] The trend of rising health insurance premiums over the lifetime of the ACA is likely to be sustained or made worse by the BGSB healthcare provisions if they become law. In a practice called “silver-loading,” insurance companies increase the premiums of silver plans, and the federal government will correspondingly increase the subsidies it provides to individuals, regardless of which metal tier they purchase a plan from.[40] However, the reverse can lead to some perverse outcomes—namely, if premiums fall for benchmark silver plans—leading to $1 for $1 reductions in subsidies—more than they fall for lower metal plans, enrollees who choose those lower metal plans could end up paying higher net-of-subsidy premiums.[41]

In 2020, 86 percent of enrollees received subsidies in some amount.[42] After the passage of ARPA in 2021, the individual market gained 2.8 million new enrollees, 91 percent of whom received subsidies.[43] This indicates that the vast majority of those with ACA plans will qualify for subsidies under the BGSB expansion, meaning that taxpayers will bear a large brunt of premium increases while consumers become more insensitive to prices. As a result, health insurance companies will have fewer incentives to lower premiums. The CBO and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) originally estimated that 2 years of the temporary subsidies provided under ARPA would add $34.2 billion to federal deficits.[44] The proposed extension through 2025 will worsen this. The inflationary nature of subsidy expansion will result in even higher healthcare spending, which already accounts for nearly 18 percent of U.S. GDP and fails to address a top priority for the nation—the high costs of healthcare.[45],[46]

The BGSB’s healthcare provisions demonstrate that liberal lawmakers’ fix for health insurance unaffordability is to increase subsidies for those that already receive them and keep pushing subsidy eligibility higher and higher up the income ladder, which only enables costs to keep rising—further increasing the federal budget deficit and creating pressure to raise taxes or crowd out other policy priorities. As evidenced above, expanding premium subsidies to those with higher income does nothing to lower premiums or control rising healthcare spending in the individual market.

Increased Federal Government Role in Healthcare

The subsidy expansions in ARPA and the BGSB wholly depart from previous means-tested government assistance by making those who earn more than four times the federal poverty level eligible for subsidized health insurance. A CBO and JCT analysis revealed that the provisions permanently expanding ACA subsidies in the first version of the BGSB would displace 1.6 million people from employment-based coverage.[47] This exceeds the 1.4 million who would newly gain coverage if the provisions become law.[48] Further, 65 percent of new enrollees will have incomes above 400 percent FPL.[49]

The significance of these impacts cannot be overstated. A phenomenon known as crowd-out will forcibly transition those who previously had good health insurance coverage from their employer to government-subsidized care in the individual market.[50] Those at lower income levels will have plans with zero cost-sharing responsibilities. These provisions significantly increase the federal government’s role in healthcare and shift more costs to taxpayers with only modest estimated gains in health coverage, mostly benefitting those at higher income levels.

Benefits to Insurance Companies

As discussed earlier, there is ample evidence to suggest that ACA subsidies are a boon to insurance companies, many of whom exercise considerable market power. One study found that “…only 50 percent of surplus generated by subsidies is passed through to consumers, while the rest is captured by firms.”[51] This lends more weight to the argument that companies are purposefully engaging in silver-loading to run up costs on the tab of hardworking taxpayers. A 2018 White House Council of Economic Advisors report found that health insurance companies profited from the ACA’s implementation, with stocks outperforming the S&P 500 by 106 percent from 2014 to early 2018.[52] They concluded this was from Medicaid expansion and the ability to charge higher premiums that the federal government largely pays. The same pattern is likely to continue if BGSB extends the expanded subsidies. In effect, the BGSB will significantly cross-subsidize health insurance companies while only moderately increasing net coverage.

INCREASED SUBSIDIES ARE NOT THE BEST OR ONLY WAY TO INCREASE ACCESS TO CARE

Background on Alternative Health Benefits

The ACA’s passage in 2010 created coverage mandates and new requirements for qualified health plans that include the provision of essential health benefits and limits on cost-sharing.[53] This contributed to the more than 143 percent increase in premiums in the individual health insurance market between 2013 to 2019 previously discussed, which particularly impacted those who did not have access to health insurance through their employer, did not qualify for ACA subsidies and were subject to the individual mandate.[54] In December 2017, the individual mandate penalty was decreased to $0.[55] New federal regulations in 2018 and 2019 made options for alternative health benefits coverage widely available, primarily through association health plans and short-term limited duration plans (though these rules are in litigation) and expanded health reimbursement arrangements.[56],[57] Altogether the rules and a 2018 Trump Administration report on how to increase choice and competition in America’s healthcare system added awareness of additional health benefit options that empower consumers to choose the coverage most appropriate for their individual health needs.[58]

More Choices Create Opportunity to Increase Access and Lower Costs

There are options outside of the ACA’s one-size-fits-all approach to health insurance. They have a long history of providing Americans with the security and flexibility they need while remaining affordable. Since states are the primary regulators of health insurance, they can determine which health benefits constitute health insurance, creating pathways to offer coverage outside of the strict regulatory framework put in place by the ACA. The flexible options and successful state models of alternative health benefits have made these plans increasingly appealing to individuals, businesses, and policymakers.

- Farm Bureau Plans: Farm bureaus are an example of member-based, non-profit organizations that can offer alternative health benefits to members in states that have provided exemptions from state insurance regulation.[59] The Tennessee Farm Bureau has offered affordable benefits outside of insurance regulated by the state for over 30 years. Research has found that plan premiums are up to 77 percent lower than other insurance options, with members having four plans from which to choose.[60] Other states have authorized similar options, including Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, South Dakota, and Texas.[61] While critics of farm bureau plans say this could decrease consumer protections, surveys of plan members have found high satisfaction levels. For example, the Indiana Farm Bureau began offering plans in 2020 and administered a survey to enrollees in 2021.[62] The results showed that 96 percent of respondents would recommend the plan to others, and 85 percent chose the health plan because of the affordability. One 57-year-old retiree stated: “With INFB Health Plans, I’m saving nearly $1,000 a month, and I’m still able to get the preventative care and access to nationally accepted providers.”[63] This model proves that exemption from one-size-fits-all ACA regulations can tailor options to the needs of members while preserving quality health benefits coverage.

- Short-term Limited Duration Plans: These plans are exempt from ACA regulation, and the Trump Administration expanded the allowable duration from three months to twelve months with the option for renewal up to three years.[64] States have varied in their response to the expansion. Arizona, Indiana, and Oklahoma codified the federal rule into state law while other states restricted the availability or flexibility of these plans.[65],[66],[67],[68] Like farm bureau plans, criticism of these plans is centered on perceptions of decreased consumer protection and impact to the viability of the individual market. In a recent analysis, expanding options for consumers did not demonstrate an adverse impact on the overall individual market.[69] In fact, a positive benefit was evident:

“Relative to states that have restricted short-term plans, states that fully permit short-term plans have had a smaller loss of individual market enrollment— particularly exchange enrollment—have had far more insurers entering the exchanges to offer coverage, and have had a greater reduction in exchange plan premiums.”[70]

Further, patient stories have demonstrated appropriate benefit distribution from the plans regulated by state insurance when a claim was made.[71]

- Health Reimbursement Arrangements: In 2019, the Departments of Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services finalized a regulation that expanded health reimbursement arrangements to give greater flexibility for employers who want to reimburse employee health expenses through integration with individual health insurance coverage and still maintain the tax-advantaged status of the contributions.[72],[73] This rule was projected to increase individual market enrollment by an estimated 50 percent and decrease the number of uninsured individuals by 800,000 by 2029.[74],[75]

CONCLUSION

The BGSB that passed the House has provisions that will lead to higher healthcare spending through inflationary subsidy structures that largely benefit insurance companies. The provisions will shift more Americans from employer-sponsored insurance to government-subsidized insurance than it will add newly insured individuals. The government should not subsidize the wealthy but should instead focus on addressing rising health premiums. The BGSB will lead to a continued increase in U.S. healthcare spending while Americans will continue to see fewer choices and flexibility in obtaining the health coverage best for them. Alternative health benefits provide an example of potential actions that states and employers can take to increase affordable, quality coverage options for Americans. The expanded ACA subsidy provisions in the BGSB are bad policy. After a decade of experience with the ACA, Americans deserve increased choices that prioritize care over coverage rather than a repeat of inflated healthcare costs.

[4]https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf (SEC. 137301)

[5] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/impact-of-key-provisions-of-the-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021-covid-19-relief-on-marketplace-premiums/

[6] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/impact-of-key-provisions-of-the-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021-covid-19-relief-on-marketplace-premiums/

[9] https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/health-plan-categories/#:~:text=Levels%20of%20plans%20in%20the,are%20available%20to%20some%20people

[11] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/explaining-health-care-reform-questions-about-health-insurance-subsidies/

[12] https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/impact-of-key-provisions-of-the-american-rescue-plan-act-of-2021-covid-19-relief-on-marketplace-premiums/

[14] https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/Trends-Subsidized-Unsubsidized-Enrollment-BY18-19.pdf

[15] https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/promises/obameter/promise/521/cut-cost-typical-familys-health-insurance-premium-/

[16] https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/Uninsured-Affordability-in-Marketplace.pdf

[18] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/dataandtechnicalinformation/ExchangesAugust2010FactSheet.pdf

[19] https://www.cms.gov/document/Early-2021-2020-Effectuated-Enrollment-Report.pdf. Effectuated enrollment is defined as individuals enrolled in coverage and paying the premiums necessary to activate the policy.

[20] https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2020/09/23/the-disappointing-affordable-care-act/?sh=7acefaad4d99

[21] https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/Uninsured-Affordability-in-Marketplace.pdf

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Health insurance plans sold in the individual market are classified into “metal levels” of bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. The metal level of a plan is determined by the ratio of cost sharing between premiums and deductibles. For example, bronze plans will have the lowest premiums and highest deductibles, while platinum plans will have the highest premiums but lowest deductibles.

[27] https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/population-up-to-400-fpl/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[28] https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/obamacares-health-insurance-exchanges-2021-increased-options-still-less

[29] Id.

[30] https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/obamacares-health-insurance-exchanges-2021-increased-options-still-less

[31] https://avalere.com/press-releases/health-plans-with-more-restrictive-provider-networks-continue-to-dominate-the-exchange-market

[36] https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/Uninsured-Affordability-in-Marketplace.pdf

[38] https://scottrasmussen.com/92-say-inflation-is-a-serious-problem-56-say-build-back-better-plan-will-make-it-worse/

[40] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/53009-costsharingreductions.pdf

[43] https://www.healthinsurance.org/blog/congress-boosted-aca-subsidies-an-enrollment-surge-followed/

[45] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet

[46] https://galen.org/assets/Expanded-ACA-Subsidies-Exacerbating-Health-Inflation-and-Income-Inequality.pdf

[48] Id.

[49] Id. The analysis estimates that “…the income of 65 percent of those who would not have enrolled without that provision would be above 400 percent of the FPL. For people whose income is more than 600 percent and 700 percent of the FPL, those estimates are 20 percent and 10 percent, respectively.”

[50] https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2021/10/19/congressional-budget-office-confirms-the-folly-and-waste-of-expanded-obamacare-subsidies/?sh=22228aa94aea

[52] https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-Profitability-of-Health-Insurance-Companies.pdf

[54] https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/data-2019-individual-health-insurance-market-conditions

[58] https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Reforming-Americas-Healthcare-System-Through-Choice-and-Competition.pdf

[59] https://paragoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/100928_OptimizedPDF.pdf; Chapter 3; p.45-46

[61] https://paragoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/100928_OptimizedPDF.pdf; Chapter 3; p.45-46

[62] https://www.infarmbureau.org/news/news-article/2021/05/10/nearly-100-of-members-surveyed-would-recommend-infb-health-plans

[63] Id.

[64] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/03/2018-16568/short-term-limited-duration-insurance

[68] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/chart/2020/state-regulation-short-term-limited-duration-insurance

[69] https://galen.org/assets/Individual-Health-Insurance-Markets-Improving-in-States-that-Fully-Permit-Short-Term-Plans.pdf

[70] https://galen.org/assets/Individual-Health-Insurance-Markets-Improving-in-States-that-Fully-Permit-Short-Term-Plans.pdf. 26 states fully permit short-term coverage.

[72] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/06/20/2019-12571/health-reimbursement-arrangements-and-other-account-based-group-health-plans

[74] Id.

[75] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-06-20/pdf/2019-12571.pdf; Table 2 on p. 28965