Covid-19 Relief Funding For K-12 Education - The Essential Role of Integrity and Accountability

COVID-19 negatively impacted millions of K-12 students across the Nation, and students with pre-existing education challenges were disproportionately impacted. School closings and distance learning/teaching amid the coronavirus crisis resulted in significant learning loss for students. Congress has appropriated $180 billion in federal relief funding to assist states in reopening schools and addressing the achievement losses for students. Unfortunately, states’ spending of these funds has been slow. The U.S. Department of Education has provided limited data on how funds have been spent to date and if investments have been effective in helping students whose families were hit hard by the pandemic. With the absence of accountability for these funds, some districts are using the aid for projects unrelated to COVID-19 pandemic relief or to addressing learning loss. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CCRSA), and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) all included significant allocations to states. Some districts have used these federal dollars to invest in track and field facilities, bleachers, and artificial turf – expenditures that question the wisdom of such robust allocations. In contrast, others have been investing in evidence-based interventions to help students recover in reading and math. One thing is clear: students’ education recovery must be at the center of the decision-making for how to use these federal dollars.

LEARNING LOSS

The term learning loss refers to “any specific or general loss of knowledge and skills or to reversals in academic progress, most commonly due to extended gaps or discontinuities in a student’s education.” The most common cause of learning loss is missing school. Missing school days impedes skill improvement and leads to a reduction in the learning levels of students. One Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget, who is known for his contribution to the field of knowledge about how children learn, has explained that students learn through assimilating new information to old information. For example, children learn math in stages. At each grade level, they build on what they know to learn new math skills. Students are assimilating their math skills to the new information. When information is lost (missed school days), students have difficulty understanding the new materials because there is no prior knowledge to connect. It is like trying to build a house with no foundation. According to 2021 research conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), remote learning had a negative impact on students’ test scores in English language arts (ELA) and math in all 12 states studied. Declines in scores were smaller for students who continued in-person learning. Passing rates in math declined by 14.2 percentage points on average. The math decline was 10.1 percentage points smaller for districts with full in-person learning. The scores varied by state. Virginia and California students, for example, had 100 percent virtual learning time during the pandemic, and experienced a 32 percent drop in math test scores during the 2020-2021 school year compared to the 2018-2019 school year. Wyoming and Florida students had the most in-person learning and dropped only 2.3% in English (Halloran et al., 2021). It is critical to understand the learning loss that occurred as a result of the pandemic in order to understand how to help students recover.

A 2021 report conducted by Stanford University estimated that student learning loss in classrooms across the country ranged from 57 to 183 days in math and from 136 to 232 days in reading during the spring of 2020. The 2021 report also documents a decline in learning for at-risk students. In 2019, 58 percent of at-risk students were reading at or above their grade levels; in spring 2021, just 31 percent were reading at their grade level. Research studies have found that children who do not read proficiently by the end of third grade are four times more likely to drop out of school than proficient readers. In addition, low literacy levels are strongly associated with unemployment, poverty, and crime. According to the National Adult Literacy Association, 70 percent of all incarcerated adults cannot read at a 4th-grade level.

The research regarding the COVID-19 and long-term impacts on students is alarming. The ongoing research on learning loss is already revealing new data as to the impact of learning loss over time. A recent study addressed the impact of school closures (internationally) on student future earnings. The researchers compared students from the top quartile of income distribution with those from the bottom quartile and found that general welfare losses are about 0.8 percentage points larger for poor children. In other words, students who experienced the longest school closures during the pandemic are predicted to earn less and be less likely to go to college (Hanushek & Woessmann, 2020). As the study describes, secondary schools in the U.S. were closed for in-person learning for longer periods than elementary schools. The researchers created a structural life cycle model along with school closure data to estimate the human capital and welfare losses of students. They examined the impact of keeping schools open during the summer as a way of compensating for the learning losses of students. Researchers found that an additional three months of schooling can compensate for more than 1/5th of the welfare losses of children induced by the COVID-19 school closures. As state leaders are working on plans for use of federal stimulus funds, using funds to address learning loss based on these new research findings should be considered.

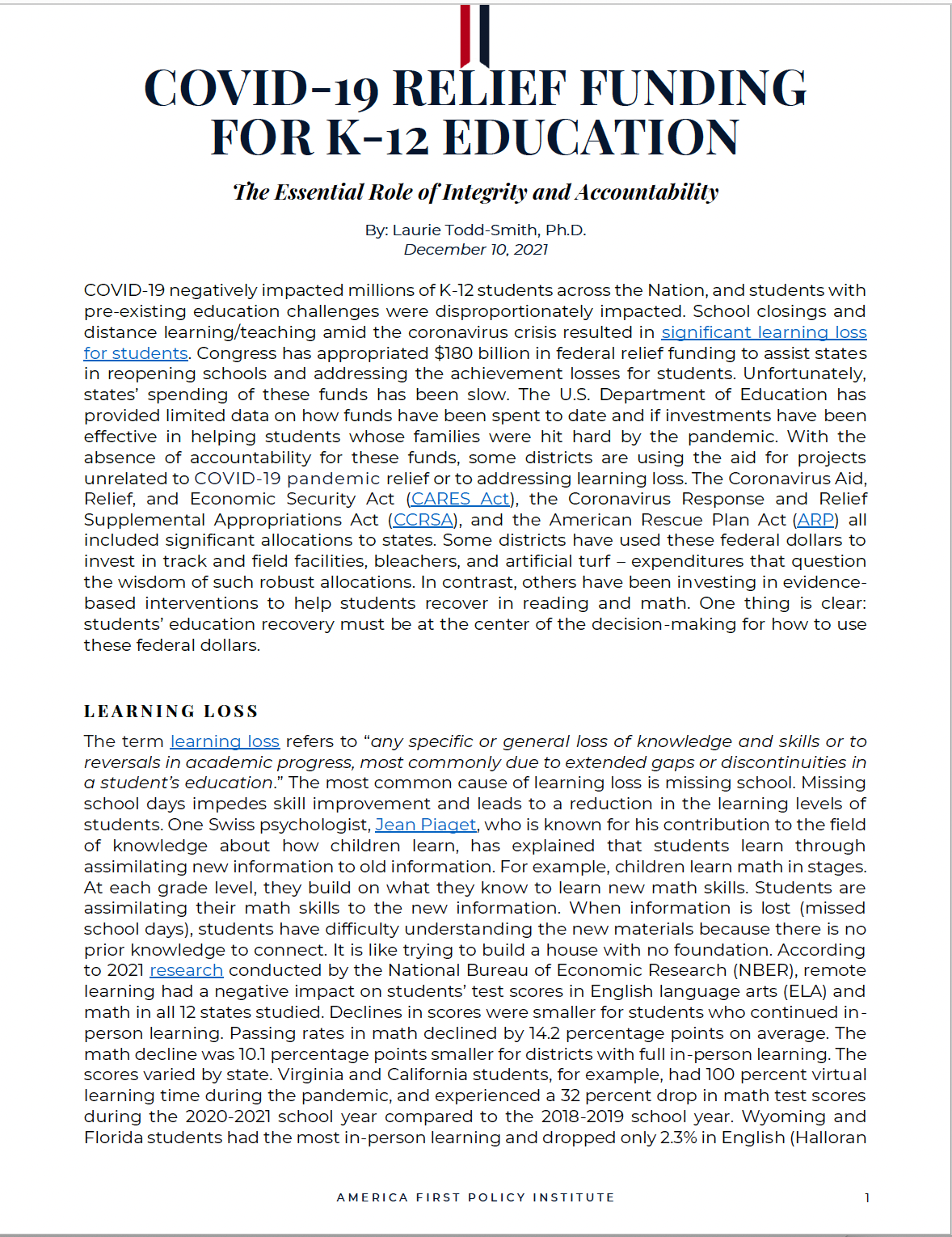

All states are struggling with learning loss. A description of the specific losses in Newark, New Jersey, is provided in Figure 1 below. Only 9 percent of students in grades 2-8 met state expectations in math, and only 11 percent of students met expectations in reading following the 2020 school closures.

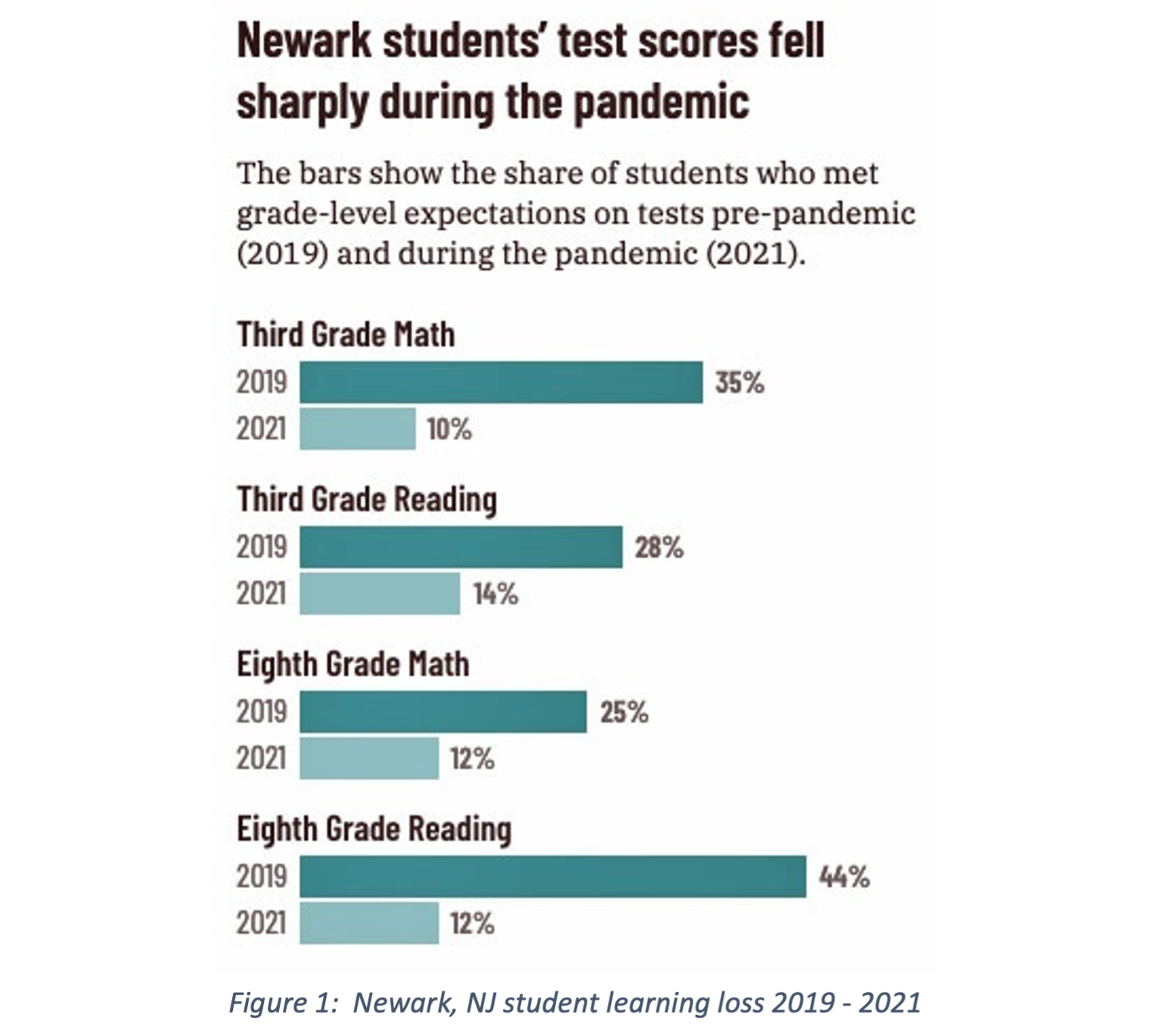

D.C. students are also struggling with significant learning loss. In 2019, 69 percent of students grades 2-8 were reading at or above their grade level, but as of spring 2021, that number dropped to 51 percent (EmpowerK12, 2021). Additionally, the research focused on percentile changes in student scores. Figure 2 below indicates an 8-12 percentile point drop in math performance and 3-6 percentile point drops in reading across grades 3-8 in the District of Columbia. The research also found evidence of the impact on the achievement of students most at-risk. Students in high-poverty schools averaged additional declines of 4-5 percentile points compared to low-poverty schools. The pandemic also impacted children ages zero to eight, and schools experienced steep declines in enrollment (up to 40 percent for preschool-age students) and slower academic growth. National testing data shows that academic declines for students in grades three to five were larger in magnitude than those for older students by 1 to 3 percentile points in reading and 3 to 4 percentile points in math. The evidence is clear; school closures impacted students both academically and emotionally. Targeted supports are needed to help students recover.

FEDERAL FUNDING

Congress attempted to assist states with addressing the critical aspects of learning loss by appropriating emergency COVID-19 relief funds. Table 1 below provides data on how much money was allocated for K-12 education system through the three federal bailouts of $180 billion from March 2020 to March 2021. For perspective, $80 billion was allocated in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The most recent of the three COVID-19 spending packages—the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act, allocated approximately $122 billion for K–12 purposes alone. For perspective, the entire U.S. Department of Education budgets for fiscal years 2020 and 2021 were $72.7 billion and $73.6 billion, respectively.

| American Recovery and Reinvestment Act | $80 billion |

| 2020 Cares Act | $13.2 billion |

| 2020 CRRSA | $54 billion |

| 2021 America Rescue P | $122 billion |

According to the U.S. Department of Education, as of August 31, 2021, state education agencies reported spending only $17.2 billion to date. Maine, Maryland, Nevada, Vermont, and Virginia have spent less than 5% of the emergency relief funds. With the learning loss, these funds must be spent efficiently and effectively. States have until 2024 to make spending commitments and the end of 2026 to spend the money. Any money not obligated or spent by those dates must be returned to the federal government. Unfortunately, the enormous influx of funding for education is resulting in the financing of projects that have little to do with helping children learn to read. The lack of any tracking methodology to date and little guidance being provided from the U.S. Department of Education and local education boards has made it difficult for researchers to determine the true cause of the slow spending of the stimulus funds. In the absence of a centralized system to track these important federal funds, it is impossible to ascertain how much of the funds are being used to close the learning gap versus are being spent on facilities and other unrelated expenditures.

The influx of the unprecedented amount of federal funds presents a unique opportunity for state leadership to use the funds to address learning loss and meet the needs of students. States need to engage in thoughtful planning and research to use the funds in ways that will help students. Investments in systemwide professional development, reading acceleration, and literacy instruction are ways states can sustain growth and make a difference for the students.

STATE SPENDING

States did receive some guidance on the appropriate use of federal funds. For instance, local education agencies (LEA’s) are required “to implement evidence-based and practitioner-informed strategies to meet the needs of students related to COVID-19.” The guidance for use of evidence-based practices includes details directing states to use funds to

“…create supportive learning environments, exclusionary disciplinary practices such as suspension or expulsion, which disproportionately impact students of color (as well as students with disabilities, English learners, and LGBTQ+ students), can be replaced with restorative justice frameworks that provide non-punitive schoolwide frameworks. Additionally, schools could consider implementation of stand-alone social-emotional schoolwide initiatives, such as the CASEL School Guide or use of curriculums with a strong evidence base, and PBIS. Schools or districts may also choose to partner with community-based organizations (CBOs) to expand mental health services or to supplement existing school counselor staff. Another resource is the Turnaround for Children Toolbox, which provides evidence-based strategies for creating school systems, structures, and practices that support students’ holistic development and learning.

The inclusion of the term evidence-based practices is not defined within the provided guidance; therefore, most ideas may have “evidence” that they work. The goal of the use of the emergency relief funds is straightforward, but there is little guidance on how exactly funds are to be used, leaving open different interpretations of the best use of the funds. For example, in a Whitewater, Wisconsin school district, the board voted to allocate almost 80 percent of their $2 million from the ESSER grant to build synthetic turf fields for the football team. The athletic director argued that he did not think the district would approve a local referendum for the football fields. The school board thus chose to spend American taxpayer dollars intended to assist with projects related to learning loss and the impact of COVID-19 on athletic facilities. An Iowa school district spent $100,000 of COVID relief money to renovate the weight room and add new floors, and now the Roland Story Community School District of 1,000 students has recently reported more students interested in wrestling and football. East Lyme School District in Connecticut spent $175,000 to address drainage problems on the baseball field. A Pulaski County, Kentucky school district spent $1 million in COVID relief dollars on resurfacing two outdoor tracks. Greater oversight is needed for the use of these federal funds.

States have submitted annual spending plans to the U.S. Department of Education. A ProPublica analysis of 16,000 school district reports from March 2020 – September 2020 found that just over half of the aid funding was categorized as “other” and did not provide insight as to how the money was spent. The guidelines provided with the funding announcement indicate that states are responsible for developing tracking systems to ensure districts are spending the money appropriately. The Georgia education department built a dashboard reflecting how much money each district has received and what programs were funded. Other states have not offered as much transparency into districts’ spending. For example, Indiana has made little information public so far, but it is currently developing an online portal.

In March 2021, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that the U.S. Department of Education system for tracking data was inadequate. The GAO recommended that “[the Department of] Education regularly collect and publicly report information on school districts’ financial commitments (obligations), as well as outlays (expenditures), to more completely reflect the status of their use of federal COVID-19 relief funds.” In 2020, the Department of Education’s Office of Inspector General reported that the “Department needed to maintain appropriate oversight to ensure that CARES Act funds were spent appropriately and in a timely manner.” In addition, the state auditor in California reported that the California Department of Education was inadequately monitoring the $24 billion in federal COVID relief funds going to school districts. The auditor recommended that the department track district spending more closely and do outreach if they are lagging in their spending, and hire more staff for this purpose. Without a systematic tracking mechanism and data on student outcomes, it is difficult to determine how the funds were used and if the funds fulfilled their intended purpose of assisting with learning loss as a result of the pandemic.

SCHOOL ENROLLMENT

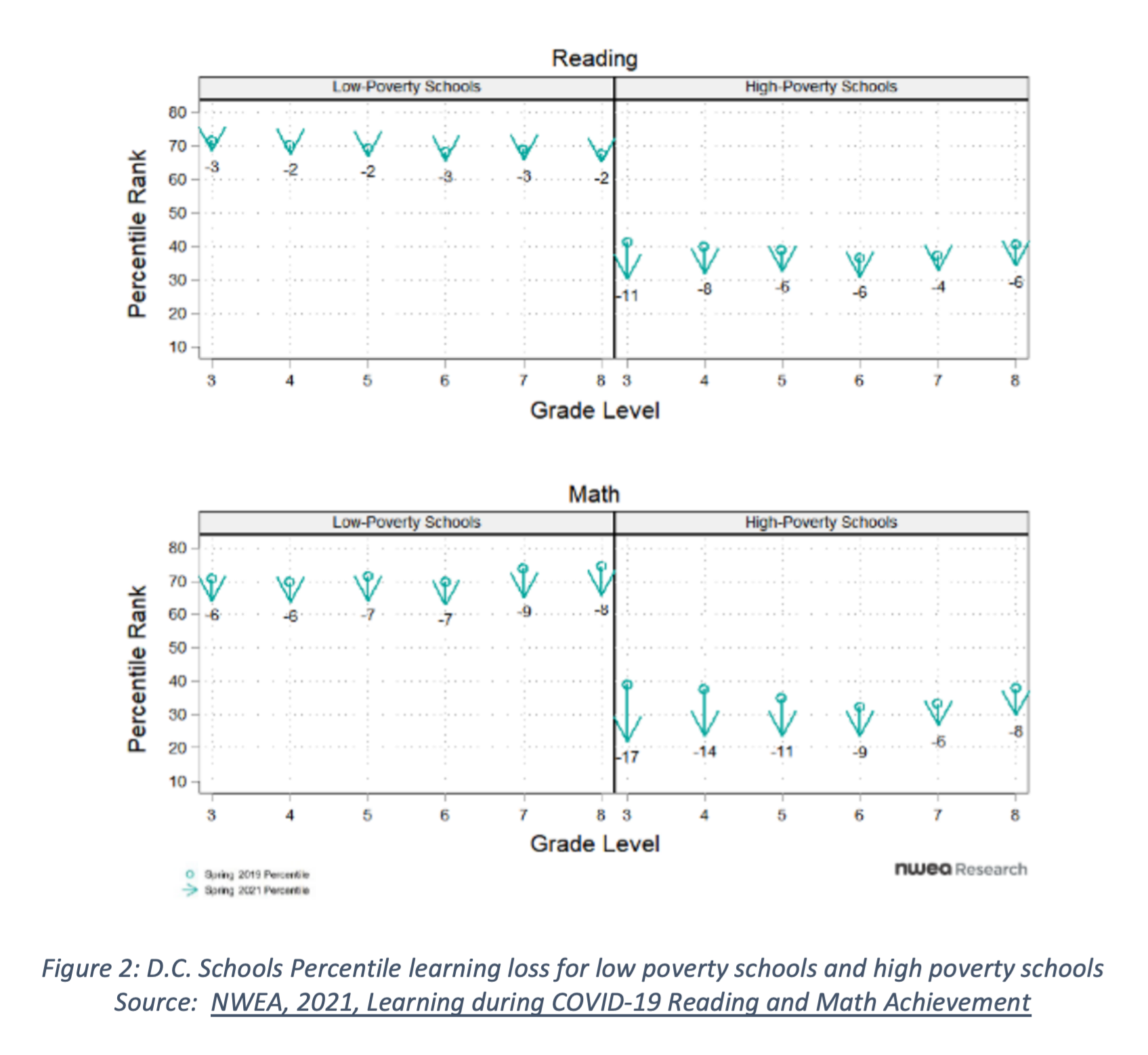

Federal education data shows that public school enrollment declined 3 percent compared to the previous year. This decline equates to roughly 1.5 million students that have exited the U.S. public education system.

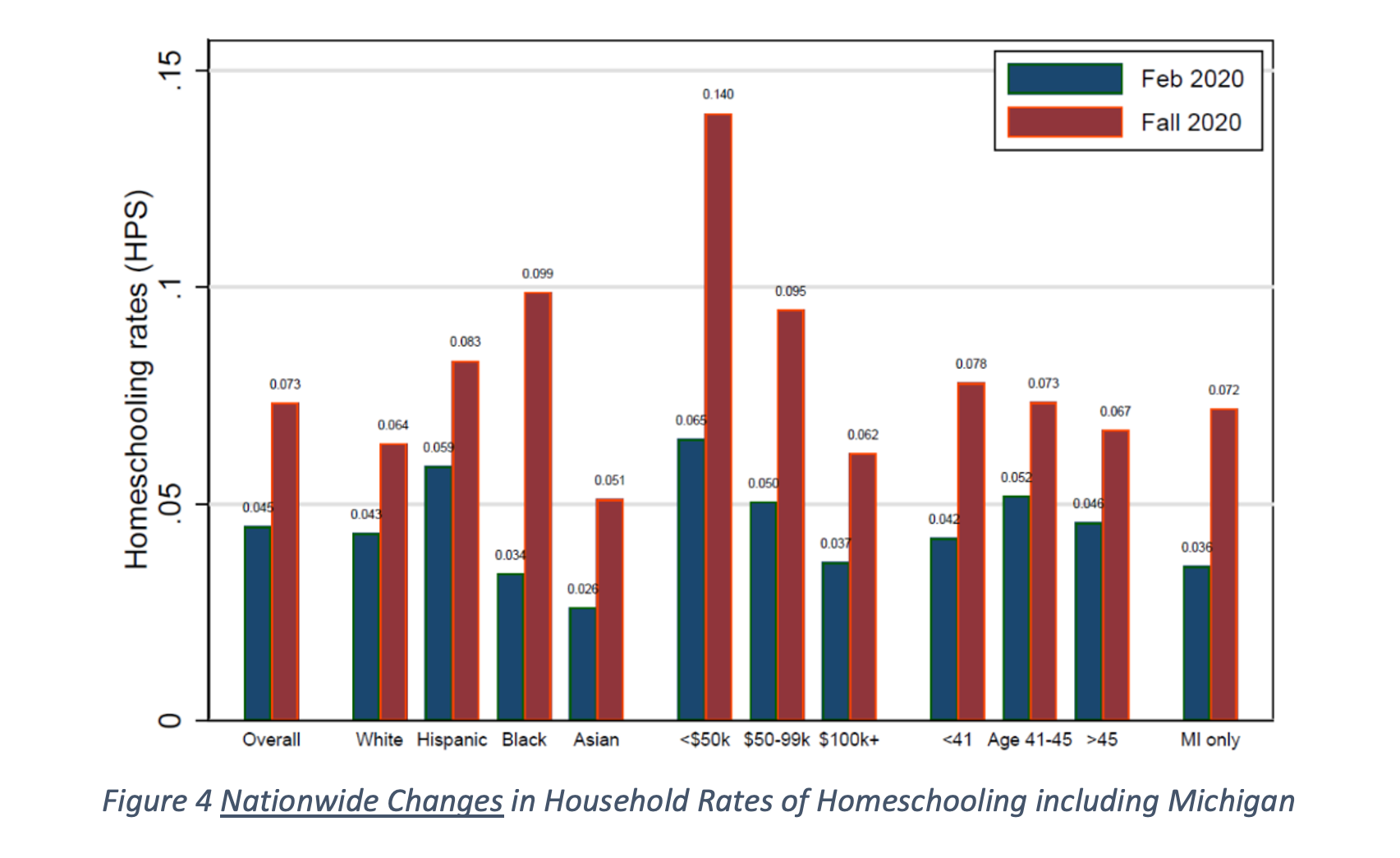

It is difficult to determine exactly how many children left public school entirely and which students left to go to private school or homeschool. Some data exists providing information about homeschooling enrollment increases. In February 2020, 4.5 percent of U.S households with school-aged children reported that at least one child was homeschooled. In fall of 2020, that rate jumped to 7.3 percent (NBER, 2021)

Figure 4 below shows the percentage of U.S. households with school-aged children who have at least one student being homeschooled. The data comes from the U.S. Census, Household Pulse Survey. In February 2020, 4.5 percent of U.S. households with school-aged children reported that at least one child was homeschooled. This rate jumped to 7.3 percent in the fall of 2020.

EVIDENCE - BASED PRACTICES

America’s children are at risk of falling behind in their education due to the school closures that occurred last year. States need to make investments in evidence-based interventions to assist schools in addressing the needs of students. Tutoring programs have been shown to help address learning loss and are considered one of the most flexible and potentially transformative learning program types available at the PreK-12 levels (Brown University, 2020). As the 2021 learning loss data continues to become available, some states are using the funds within the full scope of the American Rescue Plan appropriation language. Ohio Governor Mike DeWine signed an executive order to establish an after-school emergency enrichment education savings account using federal COVID relief funds. The program will provide care for children ages 6-18 of families with an income level of less than 300 percent of the Federal Poverty Level. The funds will help with enrichment activities and tutoring. Spending such as the after-school enrichment program helps children recover from the learning loss that occurred as a result of the pandemic.

The federal aid is supposed to bring relief to districts, but consideration for how districts will transition back to spending less must be considered, as it is not wise to use one-time revenues for ongoing expenses. As states are currently working on strategies to address student achievement and best ways to spend the stimulus funding, consideration for how to sustain investments is critical. Investments in interventions that are associated with positive student outcomes will help address the achievement gap. There are many ways states can utilize the influx of federal funds to directly help with the learning loss of students. Reading is a fundamental skill for school achievement (Hulme and Snowling, 2011). To date, eighteen states and the District of Columbia have included COVID-19 relief funding to support teacher training and instruction in evidence-based approaches to early literacy. Additionally, in the past year, four states have passed new laws or enacted regulations that mandate teachers be taught and use techniques grounded in the large body of research on how children learn to read.

Some districts and schools are working on strategies to address student achievement. Arkansas and Tennessee are creating tutoring programs to address learning loss. Kentucky is drafting guidance on the most effective tutoring programs and implementing small group instructional opportunities for students. North Dakota is introducing free tutoring for math, SAT, and Advanced Placement preparation. In all of these initiatives, parent input and feedback are critical to understanding the needs of families.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Educators and state leaders should work together in making decisions regarding the use of these emergency federal relief funds. Academic support decisions need to be designed for long-term solutions addressing the learning loss of students. The following principles can serve as an informational guide to designing state spending plans focused on students first.

- Family engagement is critical to developing family-centric strategies to support students.

- Districts should systematically collect feedback from stakeholders and share that information publicly, ensuring that it is accessible and responsive to families.

- State leaders should prioritize data in COVID-19 recovery efforts by utilizing new and existing data sources to target resources where they are most needed. Using federal funds to help improve data systems will help sustain changes over time.

- In Texas, the Houston Education Research Consortium (HERC) partnered with Houston school districts to gather survey data regarding the impact of COVID-19 on employment, education, and other mental health components. The HERC model brings together community resources and research to help districts make data driven decisions.

- Building a long term and research driven approach to building a state plan to help students is a multistep process and states could easily use the time and funding now to get started.

- States can use existing research to understand the impact of school closures on student learning.

- States can use data to identify what resources are needed the most to help address specific needs of students.

- States can use data to determine what evidence-based strategies are not working.

- States, districts, and schools should create transparency on the COVID recovery strategy based on data research. Promoting transparency will also help maintain and rebuild public trust.

CONCLUSION

The long-term effects of the pandemic will reverberate for decades, affecting education outcomes for years to come. The term “disruptive education” has always been used to describe innovation and changes that positively impact students. COVID-19 brought new meaning to disruptive education but still can be the catalyst for positive changes in education. States leaders, parents, policymakers, school administrators, and staff all play a critical role in helping students succeed. The historical appropriation of $180 billion to K-12 education should also come with a historical data collection and accountability model. Leaders need to commit to helping this generation of students towards a brighter future.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Laurie Todd-Smith, Ph.D. is a is the Director for the America First Policy Institute’s Center for Education Opportunity. She has 30 years of experience in education. She is a former preschool and public-school teacher and served 8 years as Senior Education and Workforce Policy Advisor to Governor Phil Bryant. She worked as Executive Director for the State Workforce Investment Board (SWIB) in Mississippi before being appointed by President Trump as the Director of the Women’s Bureau at the United States Department of Labor.

WORKS CITED

Boots, J. (2021, November). Unfinished learning in DC. EmpowerK12. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://research.empowerk12.org/unfinished-learning-in-dc/index.html.

Chen, L.-K., Dorn, E., Sarakatsannis, J., & Wiesinger, A. (2021, March 1). Teacher survey: Learning loss is global--and significant. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved November 22, 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/teacher-survey-learning-loss-is-global-and-significant.

CREDO at Stanford University Presents Estimates of Learning Loss in the 2019-2020 School Year. Credo (Center for Research on Education Outcomes). (2020, October 1). Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://credo.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj6481/f/press_release_learning_loss.pdf

Eggleston, C., & Fields, J. (2021, October 8). Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey shows significant increase in homeschooling rates in fall 2020. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/homeschooling-on-the-rise-during-covid-19-pandemic.html.

Halloran, C., Jack, R., Okun, J. C., & Oster, E. (2021, November 22). Pandemic schooling mode and student test scores: Evidence from US states. NBER. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w29497.

Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. J. (2011). Children's reading comprehension difficulties. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 139–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411408673

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., & Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impact of covid-19 school closures on academic achievement. Educational Researcher, 49(8), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x20965918

Musaddiq, T., Stange, K. M., Bacher-Hicks, A., & Goodman, J. (2021, September 20). The pandemic's effect on demand for public schools, homeschooling, and private schools. NBER. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w29262.

Pendharkar, E., & Riser-Kositsky, M. (2021, July 22). Enrollment Data: How many students went missing in your state? Education Week. Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://www.edweek.org/leadership/enrollment-data-how-many-students-went-missing-in-your-state/2021/07.

U.S Department of the Treasury. COVID-19 Economic Relief. https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus